Each invitation, written on thick paper, hand-sweet, heavy stock. Deckled edges.

Shadows grow long. The cicadas whir in the heat. She descends the great stairs to the foyer, taking small steps, white hand on the balustrade, pale as the travertine brought from Italian shores. The descent a diminution. Sleep was larger than this, these walls. In dreams, there are sun dappled glades and lemons and motes hanging in shafts of light. Waking, there is only dusk and the house stands still, tall ceilings full of silence. Past the banquet hall, past the sitting parlor, she enters the library and takes her place at the mahogany desk. An inclination of her white head. Dark ink strokes on paper.

“Why don’t you just call them, ma’am?” asks Renie. She brings a shawl to the older woman who allows her to drape it across shoulders. Blue veins make fine intaglios in Victoria’s skin. “It would take a lot less time, and you could be done with it.”

Victoria raises her white head. The scratching of her pen ceases. She blinks like an owl, the movement deliberate. Why does she stop me in this? It is such a small task, and a personal one, and I only have such a short time, every pause is unwelcome.

But she speaks: “And have to listen to the excuses? Or the laughter? I’d hate to hear Andrei’s remarks. No. My age makes me peculiar to them, a novelty. Those that want to come will come, and those that don’t can go hang.”

Renie listens and counts crystal, how many wine, how many water. Decanters and plate. The scratching begins again. She watches Victoria, bowed head, white and framed in lamplight. Renie sits nearby and prepares the ledger of the day’s expenses. Her food, household bills. The food, she feels guilt over—would that she didn’t eat. Victoria cares little for the maintenance of Renie’s flesh, just her own desperate integument.

§

Victoria writes:

Dearest Andrei,

I hope this letter finds you well in Arezzo. The Tuscan light at this time of year is reputedly beautiful but I would not know. It’s been years since I walked those hills with you and now, I am beginning to doubt I will ever see them again.

My hundredth birthday is fast approaching, you might remember. On the fifth of January, I will have seen a century pass and I feel it is an occasion worthy of some celebration. Please join me and the rest of our family for dinner that night. A little reunion. We will toast the century and look forward to the next. I do hope you will attend.

Sincerely,

Victoria

§

The cicadas fall silent. The air cools and fills with mosquitos, whining like far-off strains of violin, pitchy, frantic. Victoria and Renie sit on the wrap-around porch. With all of the lights extinguished behind them, they watch as fireflies burn themselves out mating, yellow streamers in the dark.

“Short lives. But the light is beautiful,” says Renie, the knitting needles in her hands moving and weaving, making small clicking sounds. She slaps her forearm, leaving a red-black smear, faint and forgotten until the bite’s welt appears.

Victoria sniffs. Maybe in response, or maybe the woman scents something upon the air. Renie cannot tell. “All lives are short. And all life is beautiful. No one wants to die.”

“I’m sorry ma’am, I didn’t mean—”

“No. It’s all right.” A hand reaches out, falls on Renie’s arm, where the mosquito bit her. It is cool, cooler than the humid air. “I know you don’t judge. But I won’t forget you, and do my best to protect you from my family. You will be taken care of.”

“Thank you, ma’am. I’m in your debt.”

“Now, I think I would like my dinner.” Victoria’s touch is dry, like parchment. It slides to her hand, fingers cupping the underside of the wrist, feather-light. Flutter of pulse. Victoria squeezes and they sit that way until the mosquitos make the night unbearable for Renie.

Summer draws on, everything hazy in the daylight, cumulus stacked upon cumulus, piling up in towering bright columns high in the arteries of air. In the morning, dewed grass runs up from the road to kiss the Pemberton manse. In the day, sunlight beats like hammerfalls, miserable for Renie as she’s alone until darkness.

Renie keeps watch for post and parcel, hiding in the porch’s shade. Packages arrive, heavy crates full of strange and wonderful items. Leaded crystal trays from Prague, sterling silver from England. Irish linens with gold embroidery. Venetian goblets. Cobalt and silver candlesticks. Filigreed iron knives from Austria. Blown glass vases from Bolivia and Peru.

Late one afternoon, after the FedEx man wheels the large wooden crate into the banquet hall and makes her sign his electric pad, Renie takes the stairs by twos and calls to Victoria, “Wake up, ma’am! Wake up! The china has arrived!” She runs to retrieve a clawed hammer.

Wearing a silk robe, Victoria walks into the banquet hall: she looks rumpled, discontent, withered. She hasn’t eaten and wears the pinched, tight expression of hunger as it works its way through her.

Renie pries open the crate lid. She has hands that match her features—blunt, solid, muscular. Victoria comes to her side, watching. Their heads bowed together. Renie reaches into the hay of the crate and removes a wad of newsprint.

“The Staffordshire Chronicle …” she says.

“It’s just a town, girl. Don’t be foolish.”

She pulls more newsprint away, revealing a white plate, almost translucent near the edges, colored with a patina of fine cracks.

Victoria says, “Bone china. Porcelain with the ground up bones of oxen added for color, clarity. Hold it up to the light.”

Renie lifts up a plate, turning it in the faint light.

“See? White as snow and almost transparent around the edges. Just like me.” Victoria laughs. It’s a dry, soft sound, like the hasp of time has knocked all the corners and hard edges from her voice.

“But what about the cracks?”

“Ah. I’ve got those too, I think.”

Victoria stands, stooping slightly, the way the aged sometimes do, looking into the crate.

“How many can we seat?” The question comes with the intonation of someone who already knows the answer, but wants to see if others know, as well.

“Twenty in here. More if we set up a table in the library.”

“No, I don’t think more than twenty will attend. Which is good,” Victoria says. Too much hazard to self and home, with so many family, she thinks, but cannot bring herself to say it.

Setting the plate in front of Victoria, Renie turns to the crate and pulls out another paper wrapped piece.

“There should be salad and bread plates in this shipment as well, Renie. They cost quite a bit. As well they should. These are very special.”

“They are pretty, and obviously old. But what makes them any better than regular plates?”

Victoria looks at her hands, turning them over. Her lip pulls back from teeth; a whiff of disgust at her traitorous body.

“This china is special because it once belonged to Dr. William Palmer, noted physician, gadabout, and serial killer. One of Britain’s first known. A notorious poisoner. He killed quite a few people with these plates.” Victoria laughs, a short dry chuff. At herself, maybe, Renie thinks—she’s looking at her hands. “Make sure they’re washed well before you eat off of them,” Victoria says.

Summer grows hot. Renie walks the mansion with paper fan, fluttering and sweating, like a moth in a closet, batting paper-thin wings. Her hair sticks to her neck, she breaths from her mouth. The heat doesn’t affect Victoria, indeed, Renie thinks the woman enjoys it—the hot breath of the world, panting. In another time, Renie might sit in her room, the window unit humming, belching out cool air, and watch the condensation form on the window. But not now. Not with Victoria asleep.

A car is heard before it is seen; crunching on the long pecan-tree-lined gravel drive. Renie peeks out of the foyer window. Shadows sit directly beneath trees, no air stirs the leaves. She goes to the door, steps out on the porch, shielding her eyes with the fan.

The driver scuttles out, black suit, black shades, white shirt, black tie—a caricature of driver. He looks at the house and shifts his shoulders as if a personal expectation has been fulfilled. He moves to the rear passenger door, opens it. A woman emerges, back straight, face blank. She’s older than Renie, younger than Victoria, but everyone is younger than Victoria. She is overly fashionable for the country, wearing form-fitting dress, showing what might have been curves twenty years earlier, but now seemed to be more gristle than fat. White pearls, maroon fabric. Bony joints, knobby knuckles and knees. Big glasses on a chain.

She approaches the porch and stops in the shade to look at Renie. She has the demeanor of a woman who works mostly with women, and consequently, doesn’t like them. Her stare is frank and appraising.

“I am Ilsa Bruhn.” She takes off her glasses and lets them dangle over her bony chest. Her accent is strange. “I am here to see Mademoiselle Pemberton. My plane arrived early. Please show me to my room.” She snaps her fingers. The driver pauses, looking at the woman, watching her mount the steps to the house. He’s a muscular man, beneath those clothes, Renie sees: he spends his hours not driving rich people around lifting weights, maybe, because men like him have only one true possession—their bodies. While women like her have not even that. She glances up toward where Victoria sleeps.

Renie opens the door, allowing the woman inside. She takes her bags from the driver herself, and his warm hand touches hers briefly and before he’s gone she raises it to her lips and tastes the sweat-salt there. She deposits the woman’s bags in the downstairs guest room. She places Vivaldi on the old turntable and sets the needle. She fixes iced tea, wedges of lemon, sugar and spoons, dainty cookies on a tray. She leaves Bruhn to sit in the dim library, sipping a glass of tea, and climbs the stairs.

She can number the times she’s awoken Victoria in the middle of the day on her hand; in all the seasons she’s been her servant, it was not something she ventured often.

Victoria lays in bed, shrouded in thick hangings. The room stands dark except for a hairline strip of light running vertically on the far wall, the seam of the heavy curtains.

“What is it?”

“A woman’s here, ma’am. She says her name is Bruhn.”

“Ah. This is good. Tell her I’ll be down after my rest.”

“I’ve put her bags in the guest room.” She keeps her voice un-modulated, no rise to the interrogative, no fall to petulance. But Victoria senses something in it, anyway.

“I’m sorry, Renie. I forgot to tell you. Ilsa is a modiste, very well-known and quite full of herself. Her dresses are coveted. The height of fashion. Make her welcome. I’ll be down when I’m down.” Victoria raises one pale hand, as if she wanted to wave Renie away, but the torpor of daylight stills that motion.

“Oh. Sorry, ma’am.” She pulls the door shut.

That evening in the library, Ilsa positions Victoria on top of a small kitchen stool and drapes her in fabrics, her mouth full of pins, a grease pencil behind her ear.

“I am not believing the heat,” she mutters. Any discomfort is an affront. “I have never felt anything like it. Paris certainly has never been this hot. Mencken called it ‘the miasmic jungles of Arkansas’ over a century ago and it seems not much has changed. Very inclement.”

“Non calor sed umor est,” Victoria says and adds, at their questioning looks, “Boarding school.”

“Muggy,” Renie says.

“What?” Ilsa asks, frowning at being addressed by the help.

“A shibboleth of the American south. I think it means ‘Moist and buggy,’” Victoria says.

“Yes. Very.” Ilsa looks around. “This would be much easier for you if we had a mirror.”

Victoria smiles at the kneeling woman. Renie knows that smile. It’s a mask, a meaningless phrase, a vocalized pause writ in flesh. It means nothing but it is something the old woman thinks she needs to do. “I trust you, dear. I know you will do a marvelous job.”

Bruhn returns her smile. “You know, you really have an amazing figure. You are very slim. I could use you on the runways of Paris.”

Bruhn stays for three more days, working through the heat, her portable sewing machine breaking the silence of the library. Renie grows weary of the company, sleeping only in the wee hours of morning, but otherwise listening for Bruhn’s movements in the house, waiting, should she try to come upstairs and find Victoria in her suite. Renie brings her coffee, sandwiches, gin. Bruhn acts as if she was a British Colonial in Calcutta; demanding fresh limes, tonic, and Tanqueray and applying DEET to herself like lotion. Cigarettes and soup, American magazines and newspapers.

“Eh?” Bruhn looks up at Renie’s appearance, placing a tray of finger sandwiches at the modiste’s elbow. “Oh, it is you.”

She leans away from the sewing machine and stretches her back. Maroon, black, and silver bolts of silk lay strewn about the room.

“Renie? Is that your name?”

Renie nods. It seems strange that this woman has ignored that fact countless times Victoria has addressed her in one another’s company. Bruhn picks up her coffee and sips.

“Let me ask you a question. Yes?”

“Okay.”

“How can this woman afford all of this? Eh? My service alone is costing her quite a bit. I am not inexpensive. Quite the opposite.”

Renie touches her neck, wiping sweat away. “I don’t know. I’ve heard her father was fabulously wealthy. A Coke distributor, I think. I don’t ask questions like that.”

“And rightly so. No matter. Her check has cleared and the money is in my account. I am not worried. Just curious.”

Before Bruhn leaves, she presents Victoria with a dress, simply cut, with elegant lines and dramatic accents. Victoria spends hours in her room, alone, the night growing late, putting on the dress. When she finally reappears downstairs, Renie’s breath catches.

“Your posture is horrible,” Bruhn says.

Victoria straightens her back, puts her shoulders together. Renie thinks of the incorruptible flesh flexing and stretching over bones, like the musculature of a cat. This does not satisfy Bruhn and she pushes her glasses further back on her nose. “The dress needs to be worn correctly. Can you wear this dress?” All of the world is a gauntlet to her, Renie thinks. Every moment a challenge. How would it be to live like that, all the time? So tiring.

Bruhn leaves the next day. Renie listens as the car diminishes down the drive, the crunching sound of gravel under wheel fading. Distasteful as the woman was, and tiresome her duties while she was guest, the company had been a relief. She loves Victoria. She faithfully keeps her safe. But her heart betrays them both—she wants for human contact. For something more than just being a witness, a sentinel.

Summer grows late, the long days grows shorter. Cooler. The pecan trees that line the Pemberton estate soon drop their heavy load onto the ground, the brown and black shells lying everywhere. Renie watches the brown squirrels grow fat among the trunks.

Renie orders a cord of firewood and ends up chatting with the burly delivery men until at twilight, standing near the side of the house, watching them stack the wood. Strong country men, they drawl their words and speak in incomplete sentences.

“This here wood. White oak. Aged this stuff all year so it should be just ‘bout right, right about now.”

“Aged?”

“Yep. Fresh cut wood smokes something horrible. This stuff’ll burn clean. You stay out here alone?”

She blushes, smiling. “No. I’m just the caretaker. I look after—” She looks toward the manse.

The man pushed his baseball cap back on his forehead with one thick, dirty finger. “That right? The old white one?”

“What?” Some people just blurt things out, saying whatever occurs to them. She wonders if the man has been drinking. His cheeks are flushed, his hands, uncertain.

“Aw. Nothing. Just when we was kids, that’s what they called her. Said she was white as chalk, walkin’ the halls. Can’t believe she’s still kickin’ around.”

Renie is startled at the thought. She smiles but keeps the laugh tamped away. “She’s still here. About to be a hundred.”

The man whistles. He touches his cap. “Whoo. Imagine that. Well, tell her thanks for the business. And hopefully we’ll be seeing you next fall.” He turns away. “You ladies be careful. A couple of folks have gone missing round Helena. Folks are nervous. Make sure you lock up at night.”

“Yes. Of course. We will.”

She writes the man a check on the hood of his truck, still ticking with the heat. He kisses the paper and winks at his boy: they climb inside the pick-up truck and rumble away. Renie turns back towards the manse, light hearted.

Victoria stands on the porch, a black figure, watching her.

“Ma’am. Are you all right?”

Victoria remains silent, unmoving. Renie runs to her.

“Is everything okay, ma’am?”

“Have you taken leave of your senses?”

“No. I—”

“Speaking to these … these day laborers? You are supposed to be inside, taking care of the household. When I woke, I called for you and got no response.”

“Oh, ma’am, my apologies.” Renie bows her head and kneels on the ground in front of Victoria. She reaches for the older woman, stops her hands in their forward motion. Victoria only allows touch by invitation.

Renie looks up to Victoria’s face. It’s still and white, mouth open. She stands there, her elbows tucked against ribs, her hands held loose, long nails pointing down. The old woman’s mouth opens and closes; it’s red, her mouth, and wet, and she pants in the twilight.

“Ma’am, I am truly sorry. It will never happen again.” This is how it ends, you are unwary for just a moment, and everything comes unraveled. “Please forgive me.”

The old woman says nothing, and her silence stretches tight enough to snap.

Renie, still on her knees, desperate for something to keep Victoria from exploring her anger. “We received some mail today. Letters. From overseas.”

“What? And you didn’t wake me?”

“Ma’am, the firewood was delivered. I needed to deal with the delivery men. I just got carried away talking to them. They reminded me of—”

“Forget about your old life. If you don’t pay attention to your responsibilities, you might lose your position in this life, now. I will tolerate no laxity in the completion of your duties. Your job here is to protect,” she brings one long finger to her breastbone. “My goddamned life. And how can you do that if you’re out making doe eyes at these country fools? Have you prepared for dinner yet?”

“No, ma’am.”

“Ah, so I must go hungry? Is that it?”

“No, ma’am. Please let me correct my mistake. Please, ma’am.” She holds up her hands in supplication as if taking communion, wrists forward. Even in the half-light of evening, the fine tracery of silver scars on her wrists are visible.

“I got rid of your predecessor. Don’t ever think I won’t get rid of you, do you hear?”

“Yes, ma’am. It won’t happen again.”

Victoria stills. A total stillness, no twitch of flesh or surge of blood. Her eyes remain fixed, open, unblinking. Mouth wet.

“You understand your situation.” Her face remains unchanged, but she closes her mouth. Renie watches Victoria, imagining whatever thoughts or emotions might churn there under the surface. She feels her own face is an open book, a signal, a ledger. Victoria’s, a cipher.

When she begins speaking again, Renie flinches, as if receiving a blow. “Renie. You’re very much appreciated here. I think of you as a child. My child. And if you stray, I will treat you like my child. With punishment. But if you are a good girl, if you perform your duties to me satisfactorily, I will raise you up, and give you a better life. Better than the one you left. Better than what you have now.”

Renie weeps. She takes the hem of Victoria’s night shift and brings it to her face.

Victoria passes a hand before her face, a gesture of weariness, or a moment’s respite from Renie’s miserable aspect. “I am hungry. Renie, stand up.”

She releases Victoria’s shift and rises. Renie’s a stout woman, but not unpleasant to the eye. She’d been athletic when she was younger, and the rigors of her household duties have kept her fit—it is a large house, with much to do every day, every night.

“Come girl.” She extends her hand, motioning the younger woman to follow. “Get the letters and prepare for dinner. I forgive you. But do not let it happen again.”

She turns and taking small delicate steps, walks into the shadows.

Renie follows.

§

Victoria,

I would be honored to attend your birthday party. A hundred years! How quickly time slips by us.

Since it has been many years since we have all gotten together, I think it might be time for a family council.

I must admit, I had to do some research to discover more about Arkansas, but it seems the perfect little backwater for a get-together. Hopefully we won’t draw too much attention from the locals.

I have recently returned from France, and learned some delightful culinary techniques there. Amazing really. I’ve gotten even fatter, if you can imagine.

Sincerely,

Andrei

§

It’s October, and the rain never seems to stop. The trees drop their leaves and the estate becomes a bog, water drenched, and muddy. The nights grow cold.

Victoria sits, blanket draped over her knees, in the library near the fire, shuffling through RSVPs.

Renie comes in, eyes down, looking at a stack of paper. Victoria does not like computers; the rattle and hum of the printer disturbs her. She’s a displaced person—removed from her era. Renie keeps their business center behind the kitchen, in the walk-in pantry. There is so little food in the house, anyway, and Victoria hasn’t entered the kitchen in years.

“Ma’am. I’m sorry to interrupt, but I will need you to make a decision on flowers. This grower can provide three hundred phalaenopsis, or two hundred coelogyne pandurata. By January the fifth, he assures me. He says that the phalaenopsis are hardier and can survive the shipping from Costa Rica with far less loss. However, the pandurata is very rare, and he is the only grower within a thousand miles.”

“I adore the phalaenopsis,” Victoria says, resting the correspondence in her lap. “However, my family is insatiable. Epicures and snobs, the lot of them. And even at my age, I cannot stand them to look down their noses at me.” She sniffs, casting a glance towards the dark window, pattering with rain. “It’s a weakness, I know. Caring. They think me a bumpkin living here.” Stillness again. Complete. She does not blink. She does not breath. Renie watches her.

“No,” Victoria says, finally. “Let us go with the coelogyne pandurata. Like the bone china, it will be a wonderful addition to the conversation. Conversation is all that we have, save one thing. The flower’s dark lip might remind Andrei of his black heart. Black orchids for blackguards.”

“Very good, ma’am. I will place the order.”

“Wait a moment, Renie. I have been reviewing the responses. It seems Andrei has been canvassing the family and we must expect more than we have prepared for. This means we must sleep thirty-five people.”

“Where will we put them all?” Renie asks.

“They’ll have to put up with some close quarters. I need to ask you to relinquish your chambers,” Victoria says.

“Of course. Will members of your family have their own, um, butlers?”

“Butlers serve the house. Valets serve the man. Andrei has always traveled with one, usually as insufferable as him. Let me see. William, Cross, Dieter and Eduardo keep valets. We can safely assume all of the women will have maidservants.”

Victoria takes a moment to consider the situation—a blank expression, staring into some middle distance only she can see. “I will write the remainder of attendees and inquire as to their arrangements. We will need to purchase the Alexander home to lodge the valets and maidservants.”

“Purchase? The Alexanders? I don’t think their farmhouse is for sale.”

“Everything is for sale. Sometimes it takes numbers for people to realize how much or how little their possessions matter to them. Don’t worry about the Alexanders. I will deal with them. But we still need to attend to the extra guests. I think it’s time to update the old carriage house.”

“It’s in a horrible state now. It looks like it’s been years since anyone lived there,” Renie says.

“It has. Twenty years or more. But it was once quite comfortable and served as an inn when I was a girl. My father acquired it long ago. As much as I dislike the idea, you will need to have some contractors come make it ready.” Victoria holds up a hand, palm out. “Yes, I know it will be expensive. Short work often is. And we will need to take inventory of the furniture, purchase new linens. And drapes. Heavy drapes.”

With that, she takes her correspondence back in hand. “Please take care of the carriage house repairs and I will deal with the Alexanders. And remember, no dallying with the help. I do not like outsiders walking about freely on the grounds. Make sure they understand that they are not allowed anywhere except the carriage house.”

“Yes, ma’am. I will.”

January draws close. Christmas passes and Victoria and Renie exchange gifts. Renie purchases a rare volume of the poetry of John Gould Fletcher for Victoria, having heard her speak of the man, his bright wit and dour moods. Victoria seems to be pleased with the gift, though it was always hard for Renie to tell.

Victoria, in turn, gives Renie a simply wrapped box. She opens it slowly. The potential of the present’s contents far outstrip anything that might be revealed inside.

It is a pistol.

“This is to protect you while you perform your duties. You never can tell who or what might wish you, or me, harm,” Victoria says. A giver of gifts that, in the end, are really intended for the giver.

The gun feels massive in her hands. She’s held guns before but she had forgotten their smell—oil and spices and the memory of fire.

“It’s not pretty. A .45 caliber. 1911 issue. They haven’t changed this model in over a hundred years. It’s inaccurate as hell, but stick it in their stomach or face and pull the trigger, they will fall.”

“They? Ma’am I’m not sure I know what to say,” Renie says. She holds it loosely in her hands—it is heavy, and larger than she thinks pistols should be when she thinks of them at all.

“Just say thank you. And keep it near you at all times. We must stay protected,” Victoria says.

The Alexanders move away, leaving their house and all the furnishings intact. Victoria signs the paperwork on the week between Christmas and New Years. Her Memphis lawyer comes by to pick up the papers the next day.

“What does she want the house for?” Florid and dressed in a dark suit, he impatiently waves his hand. “It’s just the two of you here with more space than you know what to do with. And I can’t understand why she’s having the company pay for it.”

“Investment, I guess. You’ll have to ask her,” Renie says. This is a man who needs things explained, but his need is not so great that he won’t be satisfied with the simplest. He wants for comfort, and easy answers will placate him.

“All right. Where is she?”

“Oh. I’m sorry, you’ll need to make an appointment. I’ll let her know that you request a … face to face.”

He blinks. He knows something of Victoria, then, the consternation at the prospect of speaking with her is so plain upon his face. “No. It’s not necessary. Let her buy what she wants.”

The construction crew--a group of men coming in from Dumas, Helena, and even across the Mississippi from Greenville--working furiously throughout November and December, finish the carriage house on time. Renie watches them through the warped glass windows of the back of the house, the sounds of saws and hammers bright in the winter air. She does not speak with them except in the briefest manner, delivering messages. She doesn’t know how, but should she dally with the workers, Victoria would know, even in the height of day under the thin winter sun. But it doesn’t stop her from thinking about it, about taking the foreman with the kind face and rough hands somewhere no one could see, to feel him against her.

Renie informs the crew that Victoria will grant bonus checks for each of them, to be delivered on December 31 and only if the house is complete. The men take this seriously.

New linens and drapery, art and other accoutrements, desks, vanities, sofas, chairs, lighting, carpet; all of these are needed. She hires a decorator from Memphis to finish out the interior of the house before January fifth, the day of the party. A stout little woman with broad, expressive features and short cropped hair presents herself to Renie. She tours the house, looks over the list and nods. Renie asks, “Can you do this? By the fifth?” Holding her breath. The woman smiles and says, “Cheap, fast, and good. Pick two.”

Renie doesn’t sleep, now, her excitement is so great. She spends day and night cleaning, making all spaces ready for the guests. It takes her hours to polish the silver and iron the linens. Methodically and according to place settings she had designed with Victoria, she sets the banquet hall and the library tables with the bone china, Irish silver and cobalt and gold-laced crystal goblets. She arranges the ornate pewter flowerpots, each one awaiting its own orchid. She positions candles about the house, always with an eye toward dramatic light. She lines the driveway with paper luminaria, her personal nod to the fireflies of summer, so long gone, their short lives. She becomes entranced with the ritual of trimming the candle wicks, the smell of beeswax rich and redolent in her hair, her nose. She polishes the wood and waxes the floors. She dusts the books and stocks the firewood bin in the library.

On the fifth the crates begin to arrive. They all hold different shapes. Half marked clearly as orchids, Renie has them placed in the banquet hall. But the other crates, the longer and heavier crates, she does not know how to deal with. One from Germany, another four from England. Two more from Italy. Five from Hungary. Two from Mexico. One from Spain. Two from Czech Republic. Sixteen postmarked from inside the United States. She climbs the Great Stair, dims all the lights in the hallway, and enters Victoria’s room.

“Yes?” her voice sounds dry and thin, not a little disturbed.

“The orchids have arrived and I’ve had them placed in the banquet hall.”

“Wonderful. How do they look?”

“I haven’t had a chance to see. Some other crates have arrived as well, the delivery men wait outside for directions. I don’t know what to do with them. One is from England. Two are from Arezzo. I thought we received all of the purchases?”

“Ah. Have them place the other crates in the carriage house garage. They should all fit there. Any more that arrive in the afternoon will need to be placed there as well. Once it is apparent that no other shipments are coming, go make one last round in the carriage house. Make sure all the drapes are drawn and that each room has its own orchid. Also attend to the master bedroom in the carriage house, that it has the gorgeous ceramic pot with the silver filigree. Find the most beautiful orchid and place it there. That is Andrei’s room and I do not want him disappointed. Oh, and get a damp towel and wipe the leaves at the base of every flower. They’re usually grimy from shipping.”

“Yes, ma’am. I’m so excited for the party,” Renie says.

Victoria remains silent for a long while, obscured by bed drapes. Her voice, when it sounds, is disembodied.

“Yes, it will be a party to remember. Once you’ve attended your duties, light the candles and come back here so that we might talk.”

Renie hurries off, back down the great stair and out the front door, her heart light and head full of flowers. This is what they’ve worked toward for so long, now. When the day ends, and the detritus of her orchid arranging completely erased from the banquet hall, she walks the drive, lighting the candles in the luminaria. Inside, she lights candles. The old building takes on a warm, roseate glow, crystal and silver twinkling. Renie sighs. Then, ignoring her fatigue, her heart beating fast, she mounts the Great Stairs again, excited for the evening.

Victoria sits at her vanity, combing her long white hair. She raises her eyes as Renie entered.

“Ah, Renie, come here.”

Renie approaches her, hand in hand.

“Sit.” Victoria pats the cushioned seat next to her. Renie sits.

“I have some disappointing news for you.”

“Ma’am—”

“Hush. Don’t interrupt me.” Victoria sets down her brush and looked at Renie. Her eyes are large, Renie sees, and dilated. Her skin bears the fine, web work of age—fine it appears young and old all at once. She is beautiful, Renie sees. “Brushing my hair is always so much more pleasing when you do it. I know it will be done right. However, I must resign myself to not having you around for a bit.”

“What? Ma’am, the party—I’ve worked so hard,” Renie says. It’s difficult for her to formulate words, the thoughts careen about her head so rapidly.

Victoria shakes her head, the corners of her mouth turning down. She is pale, as always, but her lips have been rouged, giving her normal pallor a blush of blood.

“I’m sorry Renie. You are important to me. An investment. This night will be—” Victoria pauses, considering the best word. “Dangerous. I’ve put too much time into you to have you lost.”

“But ma’am, I beg you. You haven’t even had any supper tonight. Let me—” She holds up her wrists to the other woman.

“No, I will sup later, with the guests. Truly Renie, it is too, too much. They are unruly. They cannot be trusted with you. And we have new members to the family that I know very little about. I must send you away.”

Renie becomes quiet. Her throat is raw and tears stand in her eyes.

“Oh, Renie. Child, do not cry. It is not the end of the world. One day you will remain by my side always. Until then, I need to protect my investment. You.”

Renie says nothing, because nothing is needed to be said. Victoria has spoken. The older woman places a knuckle under Renie’s chin and gently tilts the younger woman’s head upward.

“You are very important to me, Renie. I want you to know that.”

Renie wipes her cheek. It a trick of the will that she makes the muscles in her face turn into a smile. A puppet, an automaton, a disjointed collection of flesh, imitating the breath of life. But she can’t make the mummery extend to her eyes. She learned this from watching Victoria.

“So. Don’t be sad. Go to Memphis. Check in at the Peabody. It’s a beautiful old building. Get your hair done. Get a massage. Then come back tomorrow. All will be well then. Take the station wagon. But I need you to go very quickly. Can you do this?”

Renie remains still for a long while, unspeaking. It’s as if the immobility of the elder has possessed her. Only her eyes move in their sockets, the shallow rise and fall of her chest.

Victoria watches her. She is old enough, and changed, that her thoughts have become a wave front, many things moving at once across time: consideration for the woman before her, examination of the past, evaluation of the probable. An extrusion of probabilities, events of the night. Awareness of the building and grounds around her, suspirant and living, despite the winter chill. The mice in the attic, the slumbering moccasin beneath the house, the vermin in the walls.

Victoria nudges the younger woman’s head a little higher with her knuckle. Renie draws her head away from Victoria’s cold touch, bows her head. It is an acquiescence, of sorts.

“Good,” Victoria says. She’s holding her hand up, still, long, sharp fingers before Renie’s face. “Take care and I will see you when you get back.”

“Happy birthday, ma’am,” Renie says.

“So it is my birthday. I had forgotten. Thank you, Renie.”

Renie rises, walks to the door and to her room. She packs a small case, the .45, a make-up bag. She walks down the stairs, to the front door, and leaves among the luminaria, glowing in the night’s full dark. She looks back at the house for a moment, taking in its refulgence. She doesn’t notice dark figures that watch her from beneath the eaves of the carriage house.

In the car, driving away, Renie cranes her neck to take inventory of the items in bed of the station wagon. Heavy rope, a box-cutter, heavy duty plastic bags, duct tape.

When she reaches the highway, she turns north, drives past the Arkansas River, through the White River basin. She does not continue to Memphis. She slows and at Marvell, turns right toward Helena.

§

Many years have passed since Victoria Stith Pemberton drew her own bath. Such is the benefit of servants.

She turns the spigot, filling the old claw-footed tub. Her perception takes in the movement in the house, but she is able to focus on the task at hand—preparing her body and mind for the event. She picks up a crystal container of essential oils. The label reads “Litsea Cubeba”. She turns the decanter, letting the oil drizzle in a line from the mouth of the container to the water of the bath. A bright smell fills the bathroom.

Dropping her silk dressing gown to the floor, she stretches, her white skin shining in the light of the room. She touches herself, thinking, I was once beautiful, I was once young and not this dead thing, hidden away. Maybe I can be young again. In the tub, she lets the scented water warm her.

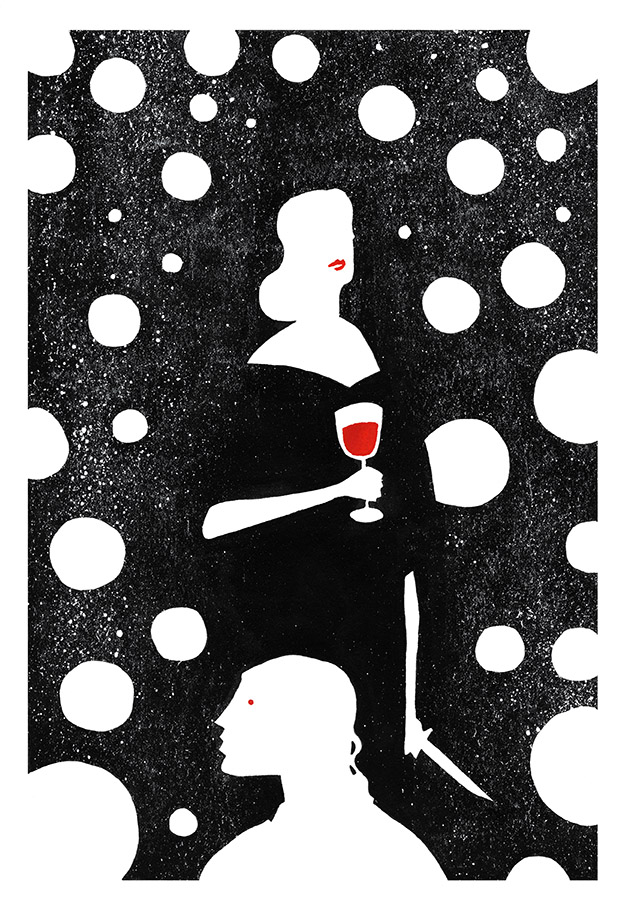

She dresses. With no vanity, makeup is pointless except for her lips. She descends the great stair. The foyer is crowded; white faces with bright black eyes watch her. The dress seems like nothing at all, the breath of air on naked skin, and the family’s gaze upon her, as she descends, gives her the sense of shrinking and expansion, all at once. She becomes gargantuan, she becomes infinitesimal. In dreams there is sunlight, and motes hanging in shafts of air, but here there is but candlelight wavering.

She moves through the crowd, nodding her head, acknowledging the stares with a tilt of her head, a hand upon an arm, the slightest curve of her lips. It is her birthday and the graces of her warmth and life linger.

“Thank you so much for attending.” She lets Francisco take her hand and kiss it. He is old, time-worn to a smoothness that even his beard cannot hide. A Pizzaro, this creature that had such ruinous effect on the Inca.

“I would not have missed it for the world. I remember when you were just a girl, traveling Europe with your chaperone. They called you a blond then. Not this!” He brought up a pale hand as if to touch her hair, stopped. Replaced it at his side. So few of them, the family, and touching without permission was an outrage.

“Milly. Yes.” She brings a hand to her throat, as if thinking. It was a gesture Mildred, her chaperone, would have made, so long ago. “I haven’t thought of her in fifty years.”

Francisco nods his head, his expression reads, yes, this is our lot, to forget all of those who once were warm. A procession of servants marching into the dusk. But he says, simply, “Please allow me to speak with you later, after the council.”

Victoria moves on. The family stands, many of them silent, aged beyond the need for talk, familiar enough with each other that the crook of a finger can indicate amusement, or disgust. The incline of a head, fury. The cant of shoulders, love.

Of all them, the loudest is Andrei. His voice floats out among the candle flames.

“… they call it gavage. It’s a technique for fattening the bird and flavoring the meat. Take a duck, and four or five months before slaughter, you pump it full of a rice and herb mixture twice a day. Supposedly the taste of herbs will suffuse the flesh. Force feeding. I’ve seen it. It’s amazing really, how people come up with these things. And geese and ducks are like pigs, they pack on the weight quickly. In that way they’re similar to humans. With the ducks their livers enlarge from which they make the foie gras …”

She enters the library, sees him standing, back to the fire, speaking to the crowd. A little troll of a man, red-haired with a forked beard and a pot belly. A devil in bespoke.

“… and they say that it flavors the meat. Obviously I did not have the opportunity to try any …”

Laughter. The patter of creatures trying to remember what it is to be amused. He looks around the room, gauging the reception of his words, and his gaze falls upon Victoria. His face twists into a smile.

“And here is the lady of honor. Our Victoria makes her entrance,” Andrei says. He has no accent, or he has all accents, and they blend into a milquetoast timbre that is indecipherable and bland.

Heads turn towards her. Men and women move forward to greet her.

Victoria claps loudly, inclining her head toward Andrei. “Everyone. I’m so glad you all could attend. Before the night gets too late and the festivities start, please ask your valets and maidservants report to their quarters. I’ve provided a small map to guide them. It would be best for the security of the guests.” She holds her hands together, as if addressing a boardroom rather than a collection of the dead. “Oh, and no driving on the grass.”

A few wander away, seeking servants that might have been foolish enough to linger after nightfall. Others remain, a room full of alabaster statues, whispering.

- you must tell us about this mansion. It seems so out of place here in the delta -

- a little bird told me you have a surprise for us, something to do with -

- these orchids. Where did you come by so many? And the black lips. Where did you -

- I can’t get over your dress. I can’t recognize the label -

Answering the questions as best she could, Victoria notices Cross moving towards the baby grand. He sits at the stool and runs through a scale, ending on a big chord, thrumming. The guests press close around Victoria.

“Let me show you around, now that Cross has taken his place. I am very proud of my home,” she says. Sometimes the way she sounds, even to herself, seems pure contrivance. I have lived one hundred years and eighty of them in this form. I should be riddled with worms, yet this nonsense—this utter drivel—sounds from my mouth. This is an act, an act of culture among wolves so they don’t devour me.

The man at the piano begins to play a piece from il Teuzzone, the aria, his long thin fingers dashing up and down the keys.

Victoria hears Andrei exclaim, “Ah! The Red Priest! Marvelous!” She moves away from the sound of Andrei’s laughter, a small group of guests following.

She begins: “The Mansion was built of cypress and oak in 1836, the year Arkansas gained statehood, by my grandfather. Lucious Gaius Pemberton. Drinking buddy of Sam Houston. Known as Lucky by his friends. A lawyer and state legislator who, I’m afraid, lined his pockets with kickbacks and bribes.” She pauses in front of a large oil painting. “This is Thomas Birch’s portrait of him. The old fiend. He shot a man on the floor of the legislature for blocking a bill that would’ve given him rights to a large tract of public land.”

She moves through the rooms, pointing out fixtures, artwork. “Here is a Rembrandt, untitled, lost from the Kunstverein München Museum in 1941. A small piece, but exquisite.” Murmurs from the comet’s tail of guest, some knowing, some appreciative.

“Remarkable little cache you have here. How did you come by it?”

“I’ve picked it up here and there, over the years. I have agents working for me,” she says.

They pass into the banquet hall. The set table gleams.

Several guests exclaim at the sight of the setting, white china shining with candlelight.

A woman says, “I miss dining. The ceremony.”

“You miss the accoutrements. The plates and knives and forks. At the heart of every family member lies a collector,” a man responds in a lazy voice. Cultured, bored, and aristocratic and British.

Victoria says, “This china is especially collectible. It was once owned by Dr. William Palmer. Palmer the Poisoner. Bone china.”

The British man smiles, but it’s another bit of farce: he is not amused, but has enough control over himself to give the politest response. He is far gone from the breath of life. “Yes. Exquisite. Palmer was a sot. Fat gibbering fool.”

A ringing sounds and Victoria turns to see Andrei standing with silver spoon and crystal goblet in hand.

He raps the side of the glass hard with his spoon. The sound fills the vaulted space of the banquet hall and moves through the mansion. The guest, dark and silent, move like ghosts toward the sound.

Andrei stands at the head of the table, the light from the candles illuminating the dark hollows of his eyes. He waits, allowing the room to fill.

“My family,” he says, smiling to all gathered around him. “We are gathered here today to celebrate Victoria’s hundredth birthday. Our youngest has finally come of age. Congratulations, Victoria. You’ve survived until adulthood.”

The crowd responds with light clapping but remains otherwise hushed.

“It being so long since we’ve all been together—indeed, there are members of the family I have just met—that I feel it is time to do a little administration.”

Groans.

Andrei makes a patting motion with his hands. “Settle, ma famille et amis.”

He sticks his hand in a pocket and cocks his hip. He looks around at the crowd. For the dead, much of the outward emotion of life falls away—happiness, sadness, anger, surprise—none of these emotions find expression on faces, even if the dynamos of their hearts still churn. Their connection to the fret and wear of life is tenuous.

Except for Andrei. When he smiles, he means it, Victoria thinks.

“Annika, Jorge, and Wilhelm. It is time for you to die. Annika, you’ve been living in Prague for over a century. Now you need to move on. At least for a generation. So the people can forget.”

A woman, dark haired and finely featured, nods, her face placid.

Jorge, a brooding dark man with heavy whiskers, says, “But I’ve only been in Sao Paolo for—I don’t know—sixty years. Why must I die?”

Andrei turns to stare at the younger man. “You must be joking. Even in Arezzo we’ve heard of the Saci, the encantado, the bloodthirsty fantasma.” He shakes his head and for an instant all of Andrei’s joviality falls away, leaving only the blank stare of the undying. “Jorge, you’ve been indiscreet,” he repeats. “It’s time for you to die. No arguments. You may have three years to wrap things up.”

He turns to Victoria. “And you, youngling. Do you want to remain here, in this backwater? Or would you move on?”

She raises her head, pushing back her shoulders. “I would leave. I would see the world, now that I am grown.”

He claps his hands together. “Wonderful. Please come stay with me in Italy for a few years and we can find a new location for you to dwell. Your first change is very important; make sure you converse with your family here. They have countless years experience at their disposal. They can advise you well, if you would listen.”

He turns back to the crowd. “A few announcements and then on to the treat. You all might have noticed Arthur D’Ensemal’s absence here tonight. I am sorry to inform you that he has died, true death. Betrayed by his valet.”

A normal assembly might gasp, or murmur. Only silence, now. Andrei holds up a razor sharp finger. “I share your outrage. But I must admonish you all; do not allow your servants too much freedom. Make sure they are trustworthy. Test them. Torture them if you must, but bend them to your will. Yes, yes, Cross. I know this is an old lecture. But I repeat; we are weak. Horribly weak. Sun can kill us. We require servants to survive, to protect us while we sleep. Our only strength is our longevity. Our hungers expose us. Do not allow yourself to become complacent. So tonight, I will workshop with you all individually; we will find ways together to make us all safer.

“I will be hearing nominations for membership in the family. Remember, the minimum net worth of the individual must be in excess of a billion. In euros, not American. And it would be nice if we could get some artists amongst us. But I realize that the minimum fiscal requirements preclude those of—” He paused and tugs on his vest, straightening the wrinkles. “An artistic bent. Of course, you may always sponsor a membership.” Andrei smiles at Cross, sitting at the piano. His old valet.

A loud thump sounds, flesh on wood, and the entire family turns unblinking eyes towards the recessed doors that lead past the sitting parlor.

Renie enters into the room, her clothes smudged with dirt and blood. She carries two small forms, one under each arm. She moves like a stevedore on a wharf, heavy laden and slow. The family parts, silently, as she enters. Once she is among them, she spills the children to the floor.

Her face fills with a sort of ecstatic joy, eyes moving from each pale, reflective face to another, as if she were in a gallery looking upon unmoving paintings.

Her hands go to her hair, and try to repair the unruly mess, tucking a strand behind her ear. Her eyes fall on Victoria.

Of all the faces, Victoria’s resembles a painting the least. Her fury stands clear; eyes narrowed, jaw taut, neck ticking with inaction.

“What have you done? Brought children here?” Victoria says.

Andrei laughs and not the feigned mirth of the dead. Victoria whips her head around to glare at him. He shrugs, crossing his arms.

She turns back to Renie. “I told you to leave. And now you’ve jeopardized everything, me, the party. Yourself, you—”

“I just—I just wanted to be here with you, ma’am. I’ve worked so hard. Look, I brought you, everyone, a present,” Renie says.

She gestures at the unmoving forms on the floor. She’s trussed and duct-taped the children solidly; their fat flesh strain at the bindings.

Victoria kneels. She feels their throats.

“You best hope to whatever god you hold dear that these children still live.”

Victoria stands. She lets the calm stillness of death settle upon her. She straightens the front of her dress and looks at Andrei. Arms crossed, he gives back nothing.

She speaks, her voice raised, so that all the room might hear. She looks among the family. Her gaze falls upon the one that might help. “William. I must ask for your help. Fetch your valet. Have these children taken to—” She looks towards Renie, hand out. “Where did you take them from?”

Renie’s limbs feel heavy and dumb. She turns from face to face, each one blank. Her gaze comes to rest on the grinning aspect of Andrei, forked beard and full lips.

“Answer, fool!” Victoria says, grabbing the woman’s arm. Renie falls to her knees.

“Helena,” she whispers. “I took them from Helena.”

William winks at her and walks to the children on the floor. He scoops them up easily in hands like shovel blades and exits the hall.

Andrei moves to stand by Victoria. He says, “I’m wondering how you’re going to handle this, Victoria. It seems that adulthood has already brought you adult decisions.”

She stills. “You old devil, you’re enjoying the situation. This girl has endangered us all.”

“Of course she did. She was ensnared by all the glamour.” He twists his voice on the last word, making it seem like a curse.

“Nonsense. She disobeyed my direct instructions.”

The group of party-goers laugh behind pale hands and whisper. She allows her awareness to expand, and contract, like metal heated by sun and cooled by night. She takes a superfluous breath of air.

She turns to Andrei. “Thank you for your concern.

Her attention distills to its essence, wave front no longer, a single point. Victoria takes Renie’s arms in her hands, looks into her face. She moves the younger woman toward the head of the table. With no effort at all she sits Renie down in a chair, her white hands like stone.

“I have told you many times that I value your service, Renie. I truly do. However, I cannot tolerate disobedience. Too much is at stake. Sit here. Do not move,” she says.

Victoria raises herself, straightening. She walks out of the banquet hall. Silence then. Renie closes her eyes. There is no sound, no rustling, no stir. She could have been alone, the silence is so complete. Yet when she opens her eyes, pale faces watch her.

One woman comes forward. She’s dressed in scarlet and her breasts are pushed up, into a simulacrum of sexual prowess, a motion started so long ago. She pinches the meat of Renie’s arm.

“A nice one. Heavy, but fit,” she says.

The man with her laughs. “Looks like Victoria has been keeping this one as her own private vintage.” He gestures at Renie’s wrists.

The woman clucks. “We all have to eat. Who can blame her? Some servants come to enjoy it.”

Victoria re-enters the room, bearing a wine bottle. The man and woman move away. Victoria picks up a cobalt and crystal wine glass and slowly twists it in her hand.

“Renie,” she says. Before, her voice was an announcement, a play for the watching eyes. But now it softens and there is something there, Renie thinks. Something more. “I am glad you have been able to join the party. It’s only fitting that the one who worked so hard on the preparations is able to attend.”

Victoria pours a glass of wine for Renie and places it in front of her.

“Drink. It will help.”

Renie takes up the glass in her hand. It does not tremble.

“You’re drinking Chateau Cheval Blanc. A 1953 vintage. My father put twenty cases of these down. This bottle is the last. What do you think?”

Renie touches glass to lips, swallows, and the rich wine paints strange and complex colors in her mouth, on her tongue.

“It’s … it’s good,” she says. She wishes she could say something more poetic, but the pale faces watch her. “It’s almost more than I can—” She stops.

“Drink,” Victoria says. The woman drinks down the glass. Victoria pours another for her. “Drink.”

When the bottle is empty, Renies eyes bead and tears run down her cheeks. She is unsteady.

Victoria pulls a chair near her and sits. She leans in close, her mouth next to Renie’s ear. “I’m horribly disappointed. I can’t believe you’d disobey me in front of all of my guests.”

She falls silent, raising her lips to show sharp, triangular teeth. It’s but a moment, and then it’s gone.

“I’m not a monster, child. I won’t slit your throat because you’ve disobeyed me. But I must punish you in front of everyone here. Do you understand?”

Renie nods, it’s all she can ask her body to do. Wine has thickened her tongue. “I’m sorry, ma’am. I just wanted to be a part of—”

“Oh, you’ve gotten that wish.” Victoria pushes back, away from the table, and stands. She rests a hand on Renie’s shoulder.

Silence again, though excitement grew in the stillness.

Victoria says, “This is my decree: You will feed whomever wishes, until they are sated. And if you live, tomorrow night we will flee this place.” She shakes her head. The corner of her mouth pulls down and the expression is not feigned. Victoria says, in a lower voice, “We had not much time here to start with but you ended our life here when you brought those children through the front door.”

Renie bows her head in acquiescence, and raises it again, to look at all of those gathered around her. She smiles. She is warm, and full of life and it is nothing to let her rapture fill her expression. As easy as breath.

“Excitement? Now?” Victoria asks.

“It’s what I was made for, ma’am. I serve,” Renie says.

Victoria shakes her head in wonder. “You surprise me.” She leans close and whispers in Renie’s ear. “Fight then. Fight us all. Stay alive through the night.”

She looks down on the woman’s face. She remains like that for a long while, watching the luminous pulse of life in her.

Victoria turns to toward her guests.

“Everyone! I would like to introduce you all to my maidservant and my valued friend, Renie Littlefield.”

The crowd moves towards the table, encircling it. Bright black and pale blank faces circle them. Andrei stands at the other end of the table, hands in his vest pockets, a sole figure grinning over the black blooms of orchids.

“Renie has been my steadfast assistant in the planning and organization of this party. She has graciously offered to provide supper for us all.” Victoria inclines her head towards the banquet, motioning the guest to pick up their glasses.

Victoria’s hand finds a knife from the table and leans forward to take up one of Renie’s hands. The blade digs into her wrist and blood flows.

“Quickly now, bring your glasses. Tonight we’ll be civilized.”

Cobalt glasses come to hands and guests move single file past Renie, each one stopping to take a measure of blood. The family doesn’t need much, though appetite, appetite always varies. Renie watches at them as they pass, life ebbing. This one dark, this one with yellowed eyes. Another with a scar, whetting lips. The woman who pinched her. The red priest with the forked beard. Victoria.

When the last glass is red, the family returns to their places, like a processional echoing liturgy, each bit of crystal a monstrance.

Andrei says, “Here’s to our birthday girl.” He raises his glass. “To Victoria! Happy Birthday. May you have a thousand more.”

Victoria smiles, showing her teeth to Andrei, making her face respond in the mummery of life. She raises her glass, crimson crystal above the bone white china.

“And to Renie. Live, girl. Live,” Victoria says.

She drinks.