If you’re a NaNoWriMo-er, take note: John Hornor Jacobs created a rough draft one November, and it turned into his debut novel Southern Gods, which garnered him a Stoker nomination. Hornor followed that up with a short story collection, and five more novels, gaining him a Darrell Award, the Golden Moonbeam Award for Children's Literature, and multiple other literary awards. His short stories have appeared or are forthcoming in Cemetery Dance, Apex Magazine, and Playboy, and he's performed with the Arkansas Symphony Orchestra. Just goes to show, if you’re working on a project for NaNoWriMo, don’t stop when the month ends!

Hornor’s work typically takes place in the southern United States (except when it doesn’t), and often carries the genre label of horror. But these aren’t your standard horror stories. No, these are the kinds of stories that peel back the layers to show us that we are just as capable as some villain of doing horrible things to ourselves and to others. Knowing we’re just as monstrous can destroy you faster than any zombie or bad guy.

So, is “Luminaria” a horror story? Does it have monsters? Not exactly, and not exactly. There’s a Steven Brust novel I’d like to compare this short story to, but if I name the Brust novel I’ll spoil the surprise. Let’s just say the thing the Brust novel and “Luminaria” have in common is that “what exactly is going on” is never mentioned outright. All the hints are there for you to figure it out at your own pace, but the characters never feel the need to explain to the reader what is so obvious to them. That sounds like it should be confusing, doesn’t it? In fact, the reality is quite the opposite. The “twist” becomes a cat and mouse game the author is playing with the reader, keeping the truth always on the next page, always in the next paragraph. Hornor pulls this writing trick off brilliantly, and the way he dances around the twist in “Luminaria” reminds me of pastel artwork that’s done on colored paper with the artist adding contrasting colors of pastels. The artist draws the highlights and the shadows, and your mind fills in the rest.

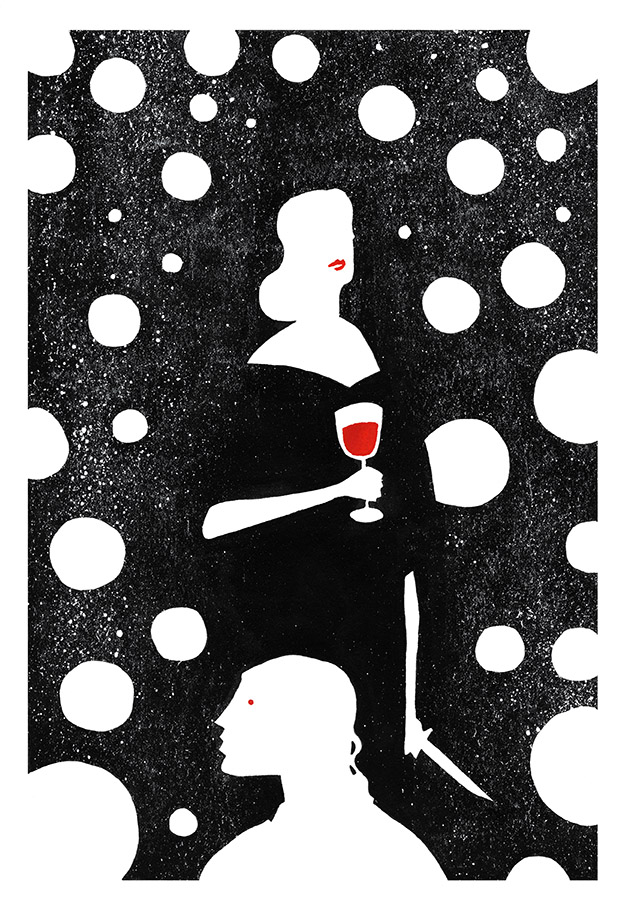

“Luminaria” is a story of fear, isolation, manipulation, loyalty, and then back to fear. Hornor puts his spin on creatures we should be afraid of, and he makes them as dangerous as they are fragile. In the grand scheme of things, Renie’s life burns as brightly and as quickly as the Luminaria she sets out for the party that will change her life forever.

John Hornor Jacobs was kind enough to chat with me about the purposeful subtlety of how this story unfolds, that Victoria is simply old fashioned (and not socially awkward, as I thought she might have been), and what living a life of fear and dependence can do to people, his new literary novel, and a new podcast that he’s working on. I’m sure that once you’ve read “Luminaria,” you’ll be itching to get your hands on more of his work!

APEX MAGAZINE: This is a super fun story to read, because you never come right out and say what these people are, instead you drop hints all over the place as breadcrumbs for the reader to follow. Most readers will see the signs and know fairly quickly what they’re looking at. And that got my thinking—why would these folks feel the need to tell anyone but their intimates who and what they are? They know what they are, they don’t need to announce it to their household every day, so it makes sense that it is never outright mentioned. Why did you choose this particular type of … what’s the best word to use … let’s go with “person” to write about?

JOHN HORNOR JACOBS: This question touches on something I’ve talked about in other posts: reading isn’t watching television. This seems obvious, but many writers feel like everything should be spelled out for the reader, that the prose should be porridge, easily digestible. I don’t look at my writing that way. I don’t feel the need for a lot of exposition in my work, I just get to the telling of the story and assume the reader will pick up what I’m talking about from context. This isn’t to say I try to make the prose difficult to understand—smooth prose is something to be praised and strived for—but I feel like if the audience has to work a little to get into a story, they’re more invested in it. This is especially true for novels, but has its place in stories as well.

This is not a popular opinion in writing circles. Most writers will tell you that you should never give a reader an opportunity to quit reading—and that’s better advice— but I’m surly.

I chose to write about vampires—can I reveal one of the main characters is a vampire? —because I think my take on them is a little different. I’ve always seen vampires as incredibly weak creatures. Yes, they’re immortal and that is their one real strength, but most of the time they’re in hiding, they only have a single source of sustenance, blood. Granted, at night, well-fed, they are something to feared, but I felt as though their lives are probably more fearful than ours. Too many dangers. So many obvious ways to kill them. Sunlight, stakes, holy items, dismemberment and beheading. And two thirds of the time, they’re helpless.

AM: As the party gets closer, Victoria seems to get more and more nervous, to the point of arming Renie with a pistol. Why is Victoria so afraid of her family? Or is the pistol just one more test for Renie?

JHJ: Again, I think vampires would live horribly fearful lives, and the prospect of having her “family” around her is a little daunting. Mostly, she would be fearful of her family, and particularly her valets and servants. She doesn’t know them, she doesn’t trust them. But this is her coming of age party, and rite of passage into the larger world of the family.

AM: You play with time and social interaction in a really interesting way. Victoria hand writes the invitations to her party at least six months in advance, china and crystal are ordered before responses come in, and people are RSVPing three to four months in advance of the event. Regarding the hand-written invitations, Victoria uses similar reasons that I use when I avoid calling people and instead send a letter, a postcard, or a text message. I want to interact with them, but I need space between what I say and what they say. Maybe it is an introvert thing, but I also I love how personal writing a letter is. Everything from the words I write to my handwriting, it feels more deliberately personalized than calling someone and just spitting out whatever words fly into my head. When you wrote this story, what were your thoughts on the slow languid way in which time flowed through the story, and in Victoria’s seemingly old fashioned methods of communication?

JHJ: Victoria would rely on this rather antiquated way of communication because she was born generations before—turned possibly because of beauty but more likely because of her parent’s wealth—and she would be more comfortable with that manner of correspondence. In some ways, her and her whole “family” is outside of the normal flow of time. Ageless, and born ages ago.

AM: The methods and the reasons behind the family’s manipulation of their servants (and sometimes each other) is as disquieting as it is fascinating. Maybe it’s just the current landscape, but I see a lot of parallels between the manipulation in the story to test loyalty, and current politics. The monster we create on the page is simply a reflection of ourselves, perhaps? Why do you think writers are drawn to writing about monsters and boogey-men, and the relationships they have with regular people? Why are you drawn to it?

JHJ: We write about monsters to convince ourselves we are not monsters. We talk about love so there might be a possibility of love for us. We tell myths of gods and divinity to convince ourselves there’s something more than this existence, something bigger than ourselves. It’s a continuous battle to pull the wool over our own eyes. But in the end, we are monsters, almost always. Or at least the capacity is always there.

As for our family of vampires, they need to always be pushing their servant’s limits to test their loyalty because their safety depends on it. By stressing their relationships, they come to an understanding of what point their loyalty might be broken. When you’re so vulnerable, you have to have an idea of your guardian’s fidelity.

AM: You and I have something in common—we work ridiculous quantities of hours at a satisfying day job, and still manage to find time for our creative pursuits. My trick is to get up really early in the morning and do creative stuff while the rest of the house is still asleep. What’s your one simple trick to making sure you have time for your creative pursuits?

JHJ: First off, congratulations on having a job you enjoy! I love mine, but it’s taken me twenty-five years in the work force to get here. I am lucky to get to make a living being creative—I’m a partner in an ad agency and its senior art director—and also be a professional writer. I would not want it any other way. A day job—a career—gives me the freedom to write what I want, how I want. It also allows my wife to focus on the kids and be their primary caregiver.

AM: You describe yourself as creatively restless. Is there a genre or story telling form you haven’t tried yet, that you’d like to?

JHJ: I am working on a more literary novel, with no speculative elements. I don’t know whether it will be published under my name or a pseudonym (or published at all). I have an idea for a coming of age thriller that I will pursue after this book, and a crime novel as well. And there are always horror novels knocking around in my head.

AM: Which writers and artists have had the biggest influence on you? Why is their work so important to you?

JHJ: I have a weird amalgam of influences. When I was young my dad read to me two books—The Lord of the Rings and Dracula—and those have colored most of my writing career. But I have a strong love of Southern literature. Flannery O’Connor, William Faulkner, Walker Percy—these are writers I always end up returning to. With LOTR and Dracula, my father sold it and imbued in me a love of the fantastic. With the Southern authors, I think I’m always trying to understand the conflicts and conundrums of life in the South. When Faulkner said, “To understand the world, first you must understand a place like Mississippi,” or in my case, Arkansas, it really stuck with me. The harshness, the privilege and poverty, the inequality, the desperation, the base ignorance, the crossroad ecclesiasts, the hucksters and showmen, the carious politicians—it’s an environment ripe for drama. But, on a more personal note, it’s often me asking “how do I come to grips with my part in this corrupt world?”

AM: Any current and or new projects you can tell us about?

JHJ: I’m working on a narrative podcast. I’ve got a partner—a top-notch audio studio that I pitched the concept to and they got on board—and we’re going to record the first episode for a Kickstarter. So I’m working on that script now. I plan to make a short film with some of my advertising resources. One of my partners is a fantastic film-maker and cinematographer, including being a great director, and he’s on board on a near dialogue-less film I’ve pitched him. Which is fantastic because he’s got professional 4k cameras and lenses, a Ronin, hd drone, light kits, whatever we need.

AM: Thanks, John!