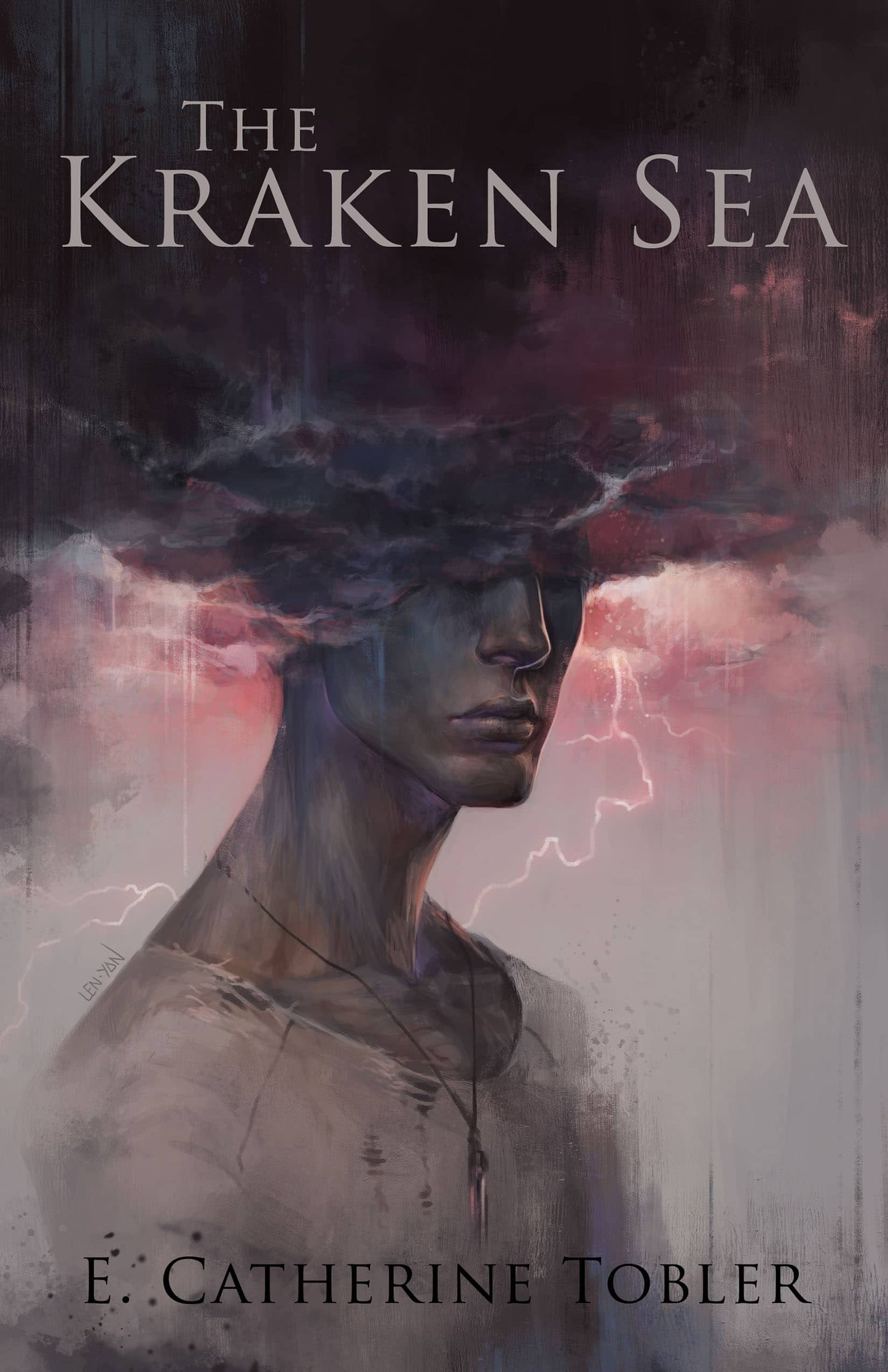

The Kraken Sea

by E. Catherine Tobler

Cover art by Magdalena Pągowska

ISBN 9781937009403

Pp. 128

Disclosure: We are an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Dark fantasy fans will love the origin story of one of E. Catherine Tobler's most memorable protagonists from her popular Jackson's Unreal Circus series. Featuring krakens, a lion tamer, and a boy making his way in a strange, strange world.

Fifteen-year-old Jackson is different from the other children at the foundling hospital. Scales sometimes cover his arms. Tentacles coil just below his skin. Despite this Jackson tries to fit in with the other children. He tries to be normal for Sister Jerome Grace and the priests. But when a woman asks for a boy like him, all that changes. His name is pinned to his jacket and an orphan train whisks him across the country to Macquarie’s.

At Macquarie’s, Jackson finds a home unlike any he could have imagined. The bronze lions outside the doors eat whomever they deem unfit to enter, the hallways and rooms shift and change at will, and Cressida—the woman who adopted him—assures him he no longer has to hide what he is. But new freedoms hide dark secrets. There are territories, allegiances, and a kraken in the basement that eats shadows.

As Jackson learns more about the new world he’s living in and about who he is, he has to decide who he will stand with: Cressida, the woman who gave him a home and a purpose, or Mae, the black-eyed lion tamer with a past as enigmatic as his own. The Kraken Sea is a fast-paced adventure full of mystery, Fates, and writhing tentacles just below the surface, and in the middle of it all is a boy searching for himself.

About the Author

E. Catherine Tobler has never run away to join the circus—but she thinks about doing so every day. Among others, her short fiction has appeared in Clarkesworld, Lightspeed, and on the Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award ballot. Her first novel, Rings of Anubis, launched the Folley & Mallory Adventures. You can find her online at @ecthetwit.

Excerpt

Something awful lingered in her eyes, something else he recognized. That look of being found strange, of being both loved and hated for it, but mostly always hated. She slithered to the cage bars and wrapped her hands around the metal. She said nothing, but her misery was clear. Her eyes were shadowed now, but Jackson saw them clear as day. Clear as this entire tent, filled with things like him.

He had worked so long and hard to learn the ways of holding himself together. Some days were worse than others. Some days, the truth of him wanted to spill everywhere like flooding water. Other days he found it easy to assume this false shape to pass unseen. But in this warm tent, he began to spill. This was why they gave him up, he had told himself over and over as he tried to find sleep. This was why his parents tucked him into a wood box and left him on the hospital’s back stoop. This was what hid inside of him, a creature that others would cage.

“Boy?”

The man and his mustache — Jackson could smell him now, oil amid the musk of the woman. But it was already too late; Jackson’s hands were no longer hands. They had vanished into the cuffs of the coat he wore, wriggling in a thousand directions as crimson scale swallowed his ordinary skin. His tight-laced shoes burst open, ruined as leg-thick coils identical to the woman’s slithered out. His trouser seams split to the knee and he made a great bellowing sound, like none he had before. His rage and fear poured out, careless, haphazard. The man and his mustache toppled backward, the woman in the cage rattling the door in a plea.

The door was little obstacle. Jackson flung one arm, enveloped two bars, and pulled. He threw the door, taking pleasure in the way it ripped through tent canvas and displays alike. He gave no thought to the others inside in the tent — was only vaguely aware of the distant shrieks as his attention rested on the man who had imprisoned Jackson’s own kind.

Much as his appendages had coiled around the bars, they now closed around the hawker’s throat. There was a burble, the sound before breath bleeds entirely away. Jackson eased his hold only slightly, because he wouldn’t finish with this man so quickly. He wanted to see the fear in the man’s eyes before he swallowed him. The hawker’s head shook, eyes blown wide and terrified, Jackson’s own true image reflected within. If Jackson had a proper mouth, he might have smiled, but his mouth was in no way proper. This gaping maw could only expand.

Read More from E. Catherine Tobler

"Every Winter" - Issue 90 of Apex Magazine

Share

- Description

- About the Author

- Excerpt

- Read More from E. Catherine Tobler

Dark fantasy fans will love the origin story of one of E. Catherine Tobler's most memorable protagonists from her popular Jackson's Unreal Circus series. Featuring krakens, a lion tamer, and a boy making his way in a strange, strange world.

Fifteen-year-old Jackson is different from the other children at the foundling hospital. Scales sometimes cover his arms. Tentacles coil just below his skin. Despite this Jackson tries to fit in with the other children. He tries to be normal for Sister Jerome Grace and the priests. But when a woman asks for a boy like him, all that changes. His name is pinned to his jacket and an orphan train whisks him across the country to Macquarie’s.

At Macquarie’s, Jackson finds a home unlike any he could have imagined. The bronze lions outside the doors eat whomever they deem unfit to enter, the hallways and rooms shift and change at will, and Cressida—the woman who adopted him—assures him he no longer has to hide what he is. But new freedoms hide dark secrets. There are territories, allegiances, and a kraken in the basement that eats shadows.

As Jackson learns more about the new world he’s living in and about who he is, he has to decide who he will stand with: Cressida, the woman who gave him a home and a purpose, or Mae, the black-eyed lion tamer with a past as enigmatic as his own. The Kraken Sea is a fast-paced adventure full of mystery, Fates, and writhing tentacles just below the surface, and in the middle of it all is a boy searching for himself.

E. Catherine Tobler has never run away to join the circus—but she thinks about doing so every day. Among others, her short fiction has appeared in Clarkesworld, Lightspeed, and on the Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award ballot. Her first novel, Rings of Anubis, launched the Folley & Mallory Adventures. You can find her online at @ecthetwit.

Something awful lingered in her eyes, something else he recognized. That look of being found strange, of being both loved and hated for it, but mostly always hated. She slithered to the cage bars and wrapped her hands around the metal. She said nothing, but her misery was clear. Her eyes were shadowed now, but Jackson saw them clear as day. Clear as this entire tent, filled with things like him.

He had worked so long and hard to learn the ways of holding himself together. Some days were worse than others. Some days, the truth of him wanted to spill everywhere like flooding water. Other days he found it easy to assume this false shape to pass unseen. But in this warm tent, he began to spill. This was why they gave him up, he had told himself over and over as he tried to find sleep. This was why his parents tucked him into a wood box and left him on the hospital’s back stoop. This was what hid inside of him, a creature that others would cage.

“Boy?”

The man and his mustache — Jackson could smell him now, oil amid the musk of the woman. But it was already too late; Jackson’s hands were no longer hands. They had vanished into the cuffs of the coat he wore, wriggling in a thousand directions as crimson scale swallowed his ordinary skin. His tight-laced shoes burst open, ruined as leg-thick coils identical to the woman’s slithered out. His trouser seams split to the knee and he made a great bellowing sound, like none he had before. His rage and fear poured out, careless, haphazard. The man and his mustache toppled backward, the woman in the cage rattling the door in a plea.

The door was little obstacle. Jackson flung one arm, enveloped two bars, and pulled. He threw the door, taking pleasure in the way it ripped through tent canvas and displays alike. He gave no thought to the others inside in the tent — was only vaguely aware of the distant shrieks as his attention rested on the man who had imprisoned Jackson’s own kind.

Much as his appendages had coiled around the bars, they now closed around the hawker’s throat. There was a burble, the sound before breath bleeds entirely away. Jackson eased his hold only slightly, because he wouldn’t finish with this man so quickly. He wanted to see the fear in the man’s eyes before he swallowed him. The hawker’s head shook, eyes blown wide and terrified, Jackson’s own true image reflected within. If Jackson had a proper mouth, he might have smiled, but his mouth was in no way proper. This gaping maw could only expand.