In the flickering amber torchlight, the mummy’s skin was burnished sienna where Jackson peeled the rotting bandages off. When Jackson pressed fore and middle fingers to the slender collarbones, the skin crinkled like tissue beneath the warmth and weight of a living body. Color bloomed through the skin and Jackson watched as one might witness a comet streaking across an otherwise dark sky; the transformation in the body was sudden and startling.

Jackson rolled the bandages from the mouth, exposing lips that were withered to almost nothing. They were black in the torchlight, a slash across the sharply emaciated jawline. Jackson sucked his index finger into his own mouth, then spread the gleaming saliva across the mummy’s lips. Beneath this attention, the black lips parted and drew a breath, though into what lungs Jackson could not say, for surely the mummy was as hollow as a box. Jackson did not think on it long, but slid a coin between those lips before bending his body across that of the mummy, before covering the mummy’s mouth with his own.

Outside the tents, he paid the seller well, not pausing to haggle; the price was already lower than it should have been, the mummy looking as any other mummy in the collection did. There was nothing outwardly exceptional about the dead body. This caused the seller’s gaze to narrow on Jackson as he loaded the mummy into the waiting truck. Mummies were cheap, often bought in bulk and used for fuel, but one did not buy a single mummy for such purposes and Jackson pulled away from the seller before questions could be asked.

Only when he had reached the safety of the circus camp once more did Jackson dare to breathe easy. He lingered in the truck though, his hands clasping the steering wheel, his heart pounding in a way it had not in a good long while. And when he walked to the back of the truck, to draw the mummy out, his heart pounded a little harder, the mummy already sitting up, already pushing the bandages from its black eyes and electrum-splattered cheeks to gaze upon the man who had found and freed it after all these centuries.

§

For a penny, the three-tongued mummy will tell you your fate. The three-tongued mummy will speak to you in sibilant whispers of the waters at the edge of the pier, the way they lick the stones as if in an effort to climb onto the pier itself. But the edge of the pier is slippery with mosses that the mummy cannot name, so the water always slides back into its place. One day, the three-tongued mummy says, you will slide down with it. When you do, you aren’t at all surprised, but the glimpse of the moon over the edge of the pier does surprise you; the mummy never mentioned the moon, nor how clear the craters looked across the half-shadowed edge.

§

The mummy stared at Jackson, trying to determine if he was known to them. There was nothing outwardly remarkable about the man, his height commonplace, his attire plain. He smelled like fruit, his fingers bent into curious shapes, and he used a cane to balance himself when he walked, but these details were not connected to the last men the mummy remembered—the men from the tomb.

Those men, two in number, had worn fine suits, no matter that the fabric had been caked with dust and sand by the time they’d reached the mummy’s vault. Those men had been armed with sharpened, wooden stakes, as if the mummy were a common vampire; they had not expected the mummy to stride from its resting place and speak to them.

“I shall call you Nefertiti,” Jackson murmured, crooked hands framing the mummy’s face though never quite touching the high cheekbones, the black lips. The eyes of the mummy were mismatched coins: the left a silver drachma bearing a sea turtle, the right a bronze shu of the Han dynasty, a precise square punched in its patina-green face. “Cleopatra is too overdone, and not … Egyptian enough …”

The mummy listened to the man’s reasoning—Nefertiti, Jackson said, embodied everything the mummy should: beauty, power, endurance. The mummy had no opinion of the queen—they had not known her, had not been her. But they had lived long enough to know that men, and the world they inhabited, never changed. No matter the year—and the mummy could not say when they saw the wheels that moved the vehicle Jackson possessed—men were in it for the money. Like the men in the tomb, Jackson had his reasons for courting the three-tongued mummy though the mummy had to admit, Jackson was better at his work than the men of the tomb. Had they abandoned their search or did it yet continue?

It was the night sky that accompanied them from the mummy seller’s place of business. Across the silent and dusty thoroughfares until they reached a spectacle the mummy could not name. A great metal serpent stretched upon the sand—no, not the sand, they realized. The serpent’s round feet rested upon long metal rails and the mummy saw how it might run far into the endless nights on such contraptions. Away from this land, the only land the mummy had known. They looked back, toward the glowing city against the horizon.

“Leaving isn’t always terrible.”

The mummy looked at the woman by their side entranced by the profusion of beard that curled from her chin. It was ornamented with beads and coins and small silver birds and the mummy felt that their eyes lingered far too long on the smallest of the coins, on those marked with owls and stags and the singular Tremissis marked with a fingerprint on its backside. A whorl in the gold, a trace of blue faience caught in the metal.

“… always terrible.” Their black mouth formed the words carefully, each word carrying a soft hiss imparted by the mummy’s split tongue.

The train, as the contraption was called, was a luxury the mummy had never known. The seat Jackson guided them to was padded and covered with green velvet. The mummy had never touched velvet before, so was entranced at how it felt when rubbed forward and back. Jackson’s hand upon theirs forestalled the exploration.

“You may have your own tent,” Jackson said. “You may have whatever you wish.”

“Whatever I wish.” The hiss of tongues again. The mummy found the notions of having and wanting amusing. Upon their death they had been marked with the notion of a curse, words of caution and terror marked upon the sarcophagus that held them, words to repel any who meant to rob the tomb of its riches. Death shall come on swift wings to who so ever touches the tomb … But those cautions had been ignored, the curse spilled onto those robbers and what else should a mummy want, but for revenge? Remove no stone or brick. Disturb no grain of sand. Unwrap no length of cloth. The mummy thought dead bodies should be beyond wanting, but it seemed they were not entirely dead after all, for indeed, they wanted.

“All beings,” the mummy said, “must be nourished if they mean to survive.”

§

For a silver stater, the three-tongued mummy will take you to Greece. The three-tongued mummy will wrap you in its rotting arms and the world will go dark, and you will think the end has come, until the darkness lifts and you see the pale pink of sunrise washing the Aegean sky.

You will think you’re dreaming, because this can’t be real; you were standing in the parking lot of the All Night Emporium, picking up a box of Tampax for your girl, but right there in the parking lot, there’d been tents set up. Where the pavement met the field, there seemed a carnival, and the mummy was there, right there, and it whispered you into its tent where the air smelled like rot and gasoline.

You took the mummy’s strangely firm hand and that hand found its way into your pocket where it found your silver stater. Your grandfather gave the coin to you when you were only five, with the promise that you’d never let it out of your sight. He picked it up when he went to Greece as a solider in the war. What war, you never knew or really cared; the coin was just shiny. You’ve never let it out of your sight until now, now when the glory of that Greek sunrise hits you.

You keep waiting to wake up, but you never do—your girl wonders where you’ve gotten to, cursing her way to the convenience store in the middle of the night when you don’t return.

§

The first night of the circus was much like something the three-tongued mummy remembered from long ago. They were no stranger to celebration or spectacle, and rejoiced in what they saw, for it was familiar. The masses of people, the tents that seemed to breathe with every wind that moved through, the pillars of fire, the games of skill and strength.

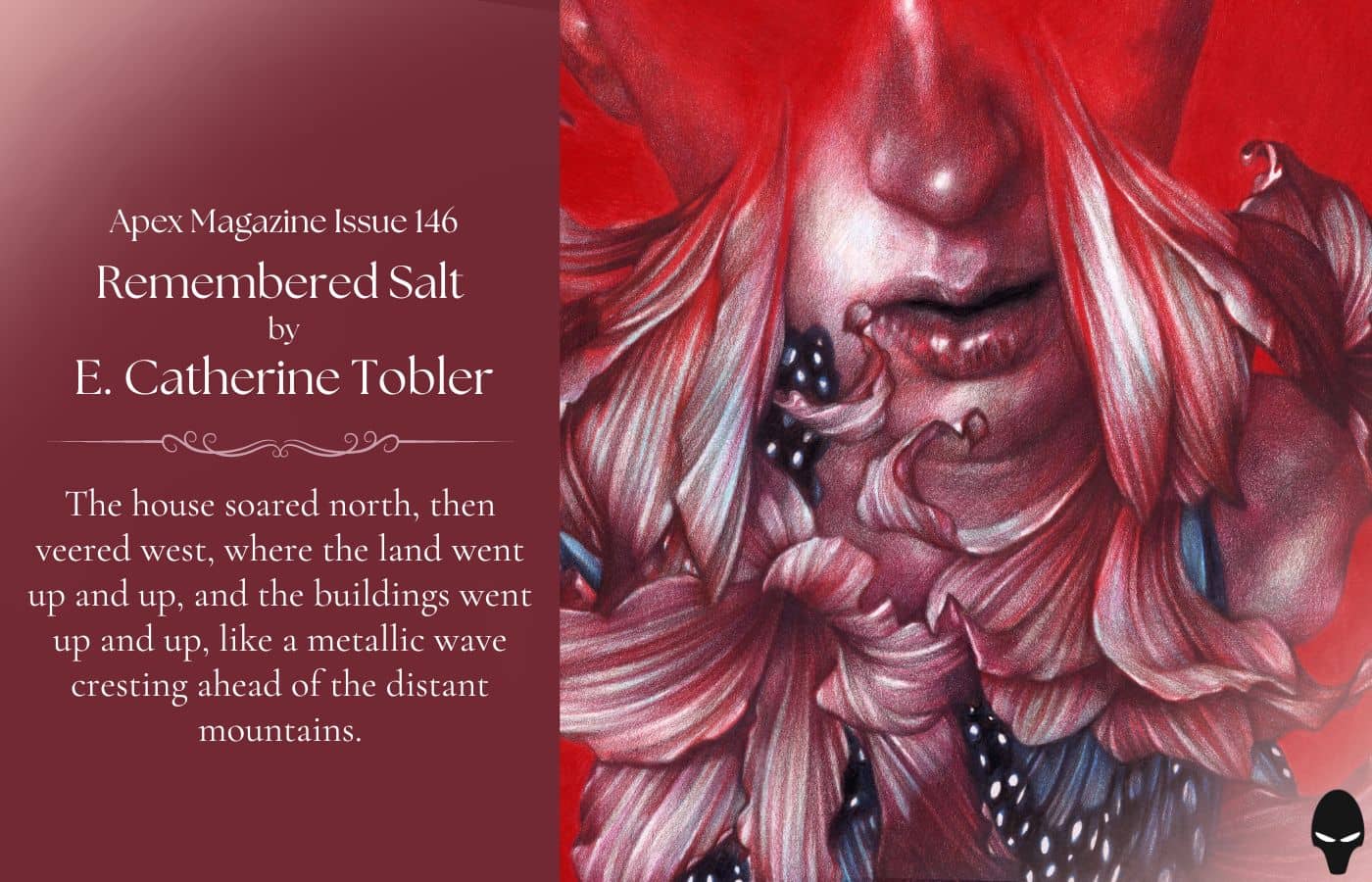

Jackson had given them their own tent, a tent that was the color of the Nile at dawn. Lit torches and long banners flanked the doorway, banners Jackson had painted himself. They showed the mummy Nefertiti in all her strange glory, Mummy Brown bandages peeling away from a body that showed no sign of withering or rot. In the background, peacock feathers fell from a blue sky, one seeming to cling to Nefertiti’s shoulder.

The mummy tried to think of themself as Nefertiti, but could not. Their own name was better said as Kek, for the ancient and unknowable darknesses that covered the world before Ra split them apart. But this name along with the curses had been lost to time and the mummy could not speak it. Their tongues would not make the proper sound, the sound of a thousand scarabs chittering in a sarcophagus.

The mummy did not understand how Jackson had come to find them in the pile of the dead. As with all dead things pulled from the ground, the mummy could only go where others took them. This was the two-fold curse, the ability to devour who they would, but only if the person approached. The mummy could not imagine what it would be to freely wander the world; it was too big by far, Cairo a world unto itself.

The circus was a city as well, overflowing with humanity. The mummy watched for the longest time, aching for each and every one of them. They could feel the coins heavy in each pocket; could feel them down to the penny in the bottom of a girl’s shoe. They could almost feel the coin between their fingers, warming under continued stroking almost the way flesh did.

Jackson did not schedule them to perform until the following night, so this night, they could wander where they would, yet could not summon the courage to walk beyond the mouth of their own tent. A locked gate stood outside it, preventing any from entering, but the mummy watched as a young man approached and read the fluttering banners by the flickering torchlight. He was unlike any young man the mummy had seen before, his eyes lined in kohl, cheekbones high and smooth and the color of the last Egyptian sunsets they could remember, when the sun had all but nearly gone and the land was smooth and black. The young man held a coin in his hand, a coin gone warm with sweat and salt as his eyes sought the banners and their message, and then the mouth of the tent.

“Is someone …” The wind picked up his voice and carried it away for a moment and the mummy thought it would not come again, but then— “Are you there?” the young man asked.

The mummy was there. They strode from the tent’s doorway, into the evening wind, where the torches could paint them gold. The young man went very still at the sight of the mummy—they knew they were startling, even without having seen their own reflection for centuries. How could it not be—a withered body that would transform under a touch, unclosing eyes of kohl and coin.

“Nefertiti.”

It was not their name, but it carried a strange power across the centuries, a weight that settled across the mummy’s shoulders. The mummy stood a little taller, bandages rippling in the wind as a gown might. The gate latch moved under their fingers and the young man’s hand slid into their own just as easily. He was impossibly slender, wrapped in black and silver and colors the mummy did not yet know, his hair cut by a razor, careless chaos against his left cheek. The mummy had so much to discover, but for now, this young man.

It never took long, the seduction and the mummy always regretted this. Mortals were easily charmed, transfixed by what they did not understand. This young man was much the same as any before him, but how prettily he kneeled, his shriek carried away by torchlight and wind.

§

For a silver tetradrachm, the three-tongued mummy will take you to the oracle. The oracle, in the flickering cauldron light that fills the crumbling temple, looks the way you think Athena should look. She is proud and fierce, and though many would not call her beautiful, you do, because pride and ferocity are the most beautiful things to you.

The oracle has thirteen breasts and thirteen testicles. They hang from her shoulders, down her chest and belly, to the split of her legs. You believe she is the most fertile creature in all creation, leaking milk and semen in equal measure when anyone gets too close. You get too close and in this space she smells like fetid dirt. Her crown is made of eggs that have cracked and spilled golden yolk down her cheeks. You could write your name in the mess of her.

You think she will know everything, but if she does, you can’t understand it. She speaks in riddles, in twists of thread. You follow these threads, but each leads you back to the three-tongued mummy. The three-tongued mummy presses you into the broken temple floor and spreads you open—yes, exactly like that—and its three-tongues work inside you until you know a new truth. When the oracle dies at the sight of you paired with the three-tongued mummy, you take her place. You have thirteen breasts and thirteen testicles and you speak in riddles to all who come. Your tongue is split by the knife the oracle left you, split into three perfectly equal pieces that leak milk and semen in equal measure.

§

The gentlemen from the tomb arrived on the second night of the circus, perhaps guided by the unsettled autumn winds that carried the scent of Egypt across the carnival grounds. Saffron and lotus and golden honeys. It was an uneasy moon that rose in the fragrant sky, ragged crescent shining feeble light across tents and amusements. The Ferris wheel arced high in the sky, slicing the moon in two if one stood in precisely the right place.

These men, Grey and Doyle by name, were old and grizzled, Victorian ditto suits showing the passage of time much as their faces did. Grey and Doyle stood at a shared height and walked with matched steps, perhaps borne out of caution, or the fact that they had traveled together for the past sixty years. They had been young men together once, but were now relics of another age, doomed across time to stalk the thing that had cursed them. Out of their element and time both, they moved cautiously through the circus, alarmed by every delighted whoop and clanging bell.

The mummy knew the men immediately and knew, too, that the men would also know them. The mummy was a unique being within the circus, and wondered what they would do when the men came to their tent. Would they welcome the men inside as they had done every other person who approached, or would the men be shunned? That the men meant to kill the mummy was certain—and the mummy would have been lying had they said the idea held no appeal. Centuries spent in the servitude of others. This was surely not the afterlife they had been promised. Where was the youthful body, where were the rivers of milk? Existence had become a burden, a weight they often wished to set down.

The mummy watched from a rip in the tent’s side as the men made their way through the crowds. Only wandering now, their eyes searching the tents and crowds for anything that looked remotely Egyptian. But when the gentlemen reached the proper tent, with its banners and windblown torches, they did not even cast a curious glance at it. Grey and Doyle did not study the waiting crowd, but walked deeper into the circus, ever searching.

Was it relief that flooded the mummy? They could not say, but a strange calm overcame them as they surveyed the crowd before the tent. Soon, Jackson himself arrived and seemed to give the mummy a conspiratorial smile as he unlocked the gate and allowed the crowd to filter toward the tent. Before the people could fill the space, the mummy took their place on the stage, stepping into the gaudy sarcophagus Jackson had made from paper, wood, paint, and glue. It still smelled like the latter as the mummy crossed their arms over their chest and appeared to be only a dead thing on display. But slowly the scent of incense overtook that of glue, and the mummy left themself drift in memories: they had walked in the mouths of the Nile once, waters soaking them up to their belly as further across the land, the pyramids had only begun to take shape. Now, they found themself here, in a distant land filled with people who longed for a taste of the strange and exotic. The mummy could not fault the people; they had much to show them.

Jackson came onto the stage, spreading his arms as he welcomed the crowd. It was close quarters, eyes already riveted upon the mummy in its case. Jackson strode a path before the viewers and began to speak in a voice that drew all the space between the centuries up tight, as if he’d cinched them with needle and thread. The mummy felt that if they stepped outside, it would be old Cairo after all, the breeze off the river cool, the pyramids half built against the setting sun.

“You have stepped back in time,” Jackson said, “and before you stands the mummy Nefertiti. Ancient queen, beautiful even in death—but is she dead? What if life lingers in this body still?”

The mummy knew its place; they moved their arm just enough to allow the bandage to spiral loose, the way a woman might allow her long hair to come unbound. A few in the audience saw, and coupled with Jackson’s words, garnered a gasp. Did you see, there it moved, no it could not have, but look the wrapping still sways—it is only the wind.

“Perhaps only the wind, or perhaps something more,” Jackson said. “Come, come, and dare look into Nefertiti’s ancient eyes.”

The crowd filtered past, up the steps and onto the stage where they could glimpse the dreaded monster and, if daring enough, touch its rotten wrappings. Most had only come to look, but there were those among them who knew the secrets—the things the mummy might also offer, those who carried special coins in their pockets and purses, those who had spoken to Jackson earlier, gaining assurances that yes, yes, after the viewing, all could be known. All would be known.

And so it was a relief when the viewing ended and the tent was closed, and people were brought in one by one, seeking an audience with the mummy, who stepped down from the sarcophagus and kneeled as if in supplication before each who had come this night. It was a relief to take the coins into withered hands. It was less of a relief when the mummy opened their mouth and extended their three black tongues. Where the coin was placed determined where one went: past, present, future. Before, during, after. Inferno, purgatorio, paradiso.

§

For a bronze coin that the Hans probably carried—a square cut perfectly into its round green face—the mummy will offer you tea. Its bandaged hands aren’t clumsy when they pour; the mummy is surprisingly nimble, considering. You will drink and the mummy will drink, the tea staining its mouth to a dark copper. You think that mouth should be withered, but it’s not. The mouth looks as plump as ever. You cannot see its teeth and you wonder if they have rotted and fallen out—surely they should have, but the slithering tongue allows no knowledge of this. Not until the mummy draws you close for a kiss do you see—no teeth, only tongues. Tongues that wrap you up and swallow you down as if you were sugar dissolved in tea. In this way you become ouroboros never-ending.

§

The mummy discovered they could stalk Grey and Doyle through the circus, passing everyone without notice. They did not understand how this was possible, but felt certain Jackson had caused it. Permitted it. It seemed nothing happened in the circus without his permission, every vile act understood and allowed through his approval, silent or otherwise.

So it was the mummy followed Grey and Doyle through the tents, pausing when they paused, to marvel at this or that. They stayed longest at the cage that held Agnessa, a creature the mummy felt an affinity for. The siren was one of the strangest creatures at the circus, raven and crimson feathers sculpting a bird's body, while ebon locks curled around her woman’s head. Her wingspan was terrible—surely she could erase the sun from the sky when she spread her wings—and her shriek likewise. It was when she spoke as any other woman that she was most terrifying to the men who stood before her. Everyone knew monsters should not speak so plainly.

“You would use this body as any other, wouldn’t you—feathers or no?” she asked them.

Grey and Doyle looked positively repulsed by her coarse words, though they did not withdraw and did not argue with her assessment. Doyle dared reach a hand into the cage, to stroke the feathers that covered her wing. She allowed the touch for a single breath, then launched herself from her perch, clinging to the cage’s bars to rattle them.

The mummy understood it was all theater; the siren was as free as any of them within the circus were. She could come and go and often spent her days flying with the little bat girl high over the grounds. But the men did not know this to be true, had only the violent evidence before them that she would eat them if given the opportunity. The mummy supposed both could be true at once: it was theater and Agnessa might still eat them. All beings must be nourished, they thought.

Reluctantly, after a meal of cotton candy and popcorn, Grey and Doyle agreed to separate, to cover more ground in this way. They felt certain witchcraft was at work, their belief that the mummy existed within the circus grounds unshaken despite having found no direct evidence it was so. Everywhere the mummy wandered, the scent of Egypt followed in its wake; it was this and this alone the men had to go on, so it was Grey who followed a tail of lotus bloom in the air, certain he would find the mummy at its end.

Of course, he did, though not in the manner he envisioned. Grey, like countless men before him, had a passion for the world’s monsters. He wanted to capture and collect each and every one, much as Jackson appeared to have. Grey’s envy at what Jackson had accomplished was palpable, a thing the mummy could almost wrap their hands around and hold.

Grey had not changed overly much since the mummy first glimpsed him in the tomb at the sarcophagus’s opening. The mummy wondered, even after all these years, if Grey had done them a favor. Were it not for Grey and Doyle, the mummy would not have woken, would have slept while this strange world passed overhead. Being drawn from its slumber was something of a gift. To discover the world through those who bought and paid for its nourishment; to carry the luckiest into realms they never imagined. These were small glories that never would have otherwise come to pass, no matter the burden the mummy felt of them.

So it was strange for the mummy to, at last, follow Grey down a path that became a dead end, seemingly a dead end within the very tomb the mummy had once occupied. Grey stopped and looked about in astonishment, no less than flabbergasted. He pressed his withered hands to the limestone wall, for only moments before there had been tent there.

“Striped fabric,” Grey whispered. “Red and cream.”

And it was strange for the mummy when Grey turned, the horror that crossed the man’s face a mirror of so many others before him. But this horror was personal—this man had cursed and blessed the mummy both, and if one could not rest, surely the other should.

“No,” Grey said, holding up a hand as if to ward the mummy off.

But no coin had been paid, so the mummy stepped forward, surprised to discover they were taller than Grey. Grey seemed so small, dwindled from the man the mummy had looked upon at the opening of the sarcophagus. Then, Grey had been young, so tall, foreboding as he bent down to gaze upon a face that had slept centuries. And now, Grey’s expression was no less filled with wonder as the mummy drew their bandages off, exposing their electrum-splattered face as if to prove who they were.

Grey fell to his knees and as men before him, implored the mummy to not do what they meant to do. But the mummy was unhearing, and kneeled before Grey, clasping the man’s head between their hands like a lover might. Tongues slithered from a mouth not dead and Grey trembled as if he would never stop. Please and no and oh no fell from Grey’s mouth, but at last it was yes when the mummy wrapped Grey within their tongues, because Grey knew the myths, knew the legends.

“Past,” Grey said, his voice gone strong once more, and the mummy carried him away, down the centuries to a far and distant place where they knew Grey believed they would wake youthful once more. But it was an old and failing body Grey woke to, blood coursing down his once-fine shirt and vest. It was the rattle of his own skeleton he heard as the mummy left him in a past he would not outlive.

§

For a gold coin of the Ottomans, the three-tongued mummy will look at you in confusion. At first, you’ll think it’s anger. It’s hard to discern exactly what those black eyes contain other than your own terrified reflection. When you set the gold coin into the mummy’s hand, it’s as if the coin tells the mummy everything. The three-tongued mummy died before the Ottoman Empire existed, and you picture the coin flooding the ancient body with knowledge. The expression in the eyes changes then; confusion becomes understanding. Every land is taken over by someone it does not belong to; every body is broken from its original construction. The three-tongued mummy almost returns the coin to your hand—it doesn’t want to know, doesn’t want this form of payment, but you shake your head and the mummy understands. You have come for a specific reason, and the three-tongued mummy will not disappoint.

§

On the third night of the circus, the mummy stalked Doyle, who was redolent with the scents of a hundred countries. His jacket was worn thin at the elbows, and along the back, and carried with it the perfume of a woman who had used it for a pillow in Dubai.

“Grey, are you in here, man?” Doyle searched the tents as best he could, but it was a constant struggle against the barkers who wanted him to attend the shows within. Doyle had no interest in the snake charmer, the Flying Doshenkos, nor even the girl who tamed the lions with her smile more than her whip. He sought only Grey.

The mummy sought only Doyle, and wondered when the circus would transform itself into the tomb again. They waited, not understanding how it had come to pass the night before. The tents seemed as solid as ever, the mummy passing unseen through the visiting hordes. It was no longer Egypt that scented the air, but burned sugar and fried dough, and the mummy lost track of Doyle twice.

Something was wrong, they thought, but did not understand until they cornered Doyle. On the far edge of the grounds, where the tents ended against the railroad tracks, Doyle turned from urinating against the train's tall wheels. Doyle buttoned his ragged fly and looked up, to stare uncomprehendingly at the mummy before him. The mummy strode closer, closing a hand around Doyle’s time-thinned neck; they could feel Doyle’s heartbeat and the panicked way the man swallowed.

The laughter was unexpected. Doyle did not cower the way Grey had, but then neither did the world change; the circus did not fall away, for the train remained exactly where it was. The mummy pressed Doyle against the train and stared as the man laughed.

“Here you are,” Doyle said, “at long last, and look at you, oh look at you, living if not breathing. Do you breathe, mummy?” Doyle did not push the mummy away, but instead pressed his hands against the mummy’s chest. “I feel no breath, no heart. Did they leave nothing inside you? Here, here.”

The mummy held to Doyle’s throat as the man searched his jacket pockets. This would be the moment, they thought, that that man offered them a coin and the power shifted. Could Doyle be that foolish, believing he could buy his way out of the mummy’s curse? The mummy might have laughed, but instead found himself quickly releasing Doyle when the man drew the mother-of-pearl belt from his pocket.

The shell was cut into oblong blocks, strung on strands of gold. It was impossibly old, like the mummy themself and by all rights should have fallen to pieces forever ago. But Doyle held the belt up and it did not fall apart, but seemed to radiate with a power the mummy could not deny. It brought the mummy to their knees. When Doyle draped the belt across the mummy’s shoulders, a ragged cry escaped the mummy.

“We found it with you in the tomb,” Doyle said, greasy fingers sliding across the mummy’s metal-splattered cheek. “Across your hips, but beneath the bandage.”

The gentlemen had stripped them bare, the mummy recalled, dragging their body from the sarcophagus, unwrapping them in the dust of the tomb. Jewels and coins had spilled everywhere, and then men had stuffed their pockets to bulging.

“It left marks on your skin, mummy. Do you bear them still?”

They did, impressions of the belt’s shells sweeping across their hips from right to left. The mummy lifted a hand, meaning to pull the belt off their shoulders now, but they could not move, seemingly pinned beneath the weight of centuries. Their own belt, once again upon their body. And all those coins, they thought, a futile attempt to reclaim what had been lost when they were unwrapped? The mummy watched Doyle circle them and could not stand, could not devour the man as planned, and all for a foolish belt. A lingering memory.

Doyle left them where they knelt, and it was only sometime later the mummy managed to close their hand around the shells and pull them free. They bundled the belt into their robes, carrying it as one might something excessively hot, and only once in their tent did they unroll and look at it anew. It glowed like starlight and with a shriek, the mummy hurled it into the nearest cauldron of fire.

§

For an electrum coin that bears the image of a falcon soaring, the three-tongued mummy will close its tent flap and let you be. Inside its closed tent, the three-tongued mummy will sweep the bandages free from its head, and touch the gleaming electrum that still covers its own bare head, the electrum that dribbles down its eye and across its cheek. The three-tongued mummy will swallow the coin and remember—though it need not swallow the coin to remember. The wind is cold in this place and this place is not Egypt, but the mummy wills it to be.

§

The mother-of-pearl belt did not melt. The fire went out overnight and the mummy pulled the still-warm belt from the cauldron; wrapped it around their hips and exhaled at the weight of it against them. They wrapped themselves back into their bandages and robes, and the belt pressed close across their hips and they knew a strange measure of comfort.

They found the bearded lady in the food tent, cupping a tin of coffee while the wind swirled warm ahead of the evening storm. The mummy could feel the change coming, their skin strangely loose over their bones for the first time in centuries. They felt filled, and perhaps it was consuming Grey that left them this way—they were unsure, for it seemed the loss of Doyle should have been more impactful.

“Kek,” Delilah said as the mummy sat and they felt comforted that someone knew their name. She pushed her coffee across the table and they did not drink, but bowed their head to inhale the wonderfully warm scent. The only other figure in the tent was Pasha Doshenko, but they moved on after collecting a cup of coffee from the battered pot Delilah had brewed.

“We move tonight?” the mummy asked Delilah. Their eyes traced the careful ornaments in her beard, pausing again on the coin with its trapped blue faience.

Delilah nodded. All things came to an end, and so too the circus’s time in this city. The mummy wanted to ask where they were, but it did not matter. Not when they sat within reach of the gold coin.

“Can you take it or must it be given, mummy?” Delilah asked.

The mummy was startled into sitting straight, lifting their eyes to Delilah’s. Her gaze did not waver, so the mummy ensured their own did not. But inside, they wavered. It was a strange question to be asked and they did not know. People had given them coins across the centuries; the mummy had carried people to wonderful and terrible places in return. Had bestowed fortunes and fates and they did not know how the magic worked, only that it did. Only that ever since they had been unwrapped in the tomb, their burial treasures scattered, they had roamed, unable to rest.

Now, the mummy reached for Delilah’s beard, stroking their fingers carefully over the coins and ornaments. “I do not know,” the mummy said, their voice soft and spilt three ways through their tongue. “Do not give it to me.”

They sat there, the pair of them, unmoving while the sun painted its way up the back of the tent. They became aware of distant noise in the carnival grounds, people preparing for the last evening ahead, and what a show it would be, Jackson murmured as he passed the tent, his arm looped through someone else’s. When the mummy took the coin in hand, they looked at Delilah sadly.

“If I take this,” they said, “you will see.”

“Open my eyes,” Delilah said.

§

For a gold Tremissis bearing the image of Saint Michael, marked with the mummy’s fingerprint and faience besides, the three-tongued mummy will carry you to the archangel himself, in the moment after he killed the serpent. The ground is thick with black blood, and it wells over your bare feet—you were wearing shoes, weren’t you, but now you are not, nor is Michael. Michael stands clear of the muck; it seems to actively ebb and flow around him, wary of touching him even when its host body has perished.

The serpent seems dead enough; Michael says you may touch him to be certain, and when you do, the skin transforms. Serpent becomes a dragon, green-scaled, its fanged mouth gaping open. You can see his tongue, thick and black, and it is split like the mummy’s. This startles you so, the three-tongued mummy’s hand slides around your neck. We all have an origin, the mummy tells you, and the sword of the archangel burns bright, hungry still.

§

You may have whatever you wish.

Jackson had spoken the words upon the mummy’s arrival and though they did not wish aloud, their most secret of hearts did, and so it was Doyle stood among those who would enter the mummy’s tent on the final night of the circus. Doyle looked much as he had the night before, in his worn suit, in his worn face. The mummy, standing still in its new sarcophagus, watched Doyle through their coin eyes, the man casting worried looks to the stormy sky. Lightning brightened the world beyond the torches flanking the tent flaps and thunder trembled in everyone’s bones.

By the time Jackson had ushered everyone inside, it was steadily raining. The showman did not seem to care—he was drenched to the skin and the mummy saw then that Jackson was not mere skin and bone; something lingered beneath the surface he showed everyone, something scarlet and slithering. The mummy felt calmed by this notion, that everyone in the room concealed something beneath their skins, that none were as they seemed, for surely the mummy was not. The mummy breathed and breathed again, and Jackson spread his arms to the crowd before them.

“You have stepped back in time,” Jackson said, “and before you stands the mummy Nefertiti. Ancient queen, beautiful even in death—but is she dead? What if life lingers in this body still?”

The mummy knew its place and kept to Jackson’s script, though they wanted very much to lunge for Doyle within the crowd. They moved only enough to allow the bandage against their arm to unwind, exposing the burnished sienna of their skin to the crowd. It was children who gasped this time and pointed, one boy yelling and fleeing the tent despite the rain pouring from the dark sky.

“Perhaps only the wind, or perhaps something more,” Jackson said. “Come, come, and dare look into Nefertiti’s ancient eyes.”

The mummy waited. Waited while men and women and children passed them, fingers daring to stroke their withered body through the rotting bandages. Only the body wasn’t so withered, and sometimes moved, and in this way the people got more than they paid for, shrieking when the mummy moved, or in some cases, daring to linger. One young child wrapped their hand around the mummy’s own, and pressed a kiss against the back. The shock of warm lips on the other side of the bandage emboldened the mummy; they let their fingers slide over the apple curve of the child’s cheek, through raven locks, and away. Some were never afraid.

Doyle approached the mummy without fear that night. The mummy watched him come, chin thrust out, every step confident. The crowd had vanished and Jackson alone stepped down from the stage, to close the flaps of the tent, to leave Doyle and the mummy alone at long last. The mummy drew the stormy air into its hollow body and stepped out of the sarcophagus to meet Doyle.

“You do breathe,” Doyle said.

“Now and then,” the mummy allowed, pushing the bandages from their bare head. They advanced on Doyle and Doyle held his ground as the mummy shed its wrappings. Shed them until they wore only the belt they had worn in death, gleaming mother-of-pearl encasing hips that should have gone to rawhide. But their body was smooth, flush with life, and they appreciated the way Doyle stared, and finally took a step backward at the sight.

“Cursed creature.”

Doyle spat at the mummy’s feet, and the globule was surprisingly warm beneath the mummy’s foot as they approached. Doyle turned and leapt from the stage, covering the distance to the flaps in five running strides. But the flaps did not open, but for to allow Doyle to see a sliver of the world he would never again enter. He tasted the wind-flung rain upon his lips, but could not open the tent flaps. Could only turn to face the mummy when they approached, when they took him gently in hand.

The mummy supposed their own people had done a better job of opening bodies with careful tools, to extract what was hidden inside. As it was, the mummy had only their hands, fingers elongating to liquefy and prise the brain from Doyle’s skull, to pull with wet and viscous fury each lung from his ribcage. The mummy left the heart as was always done—for the heart held the mind, the soul, and the mummy wanted to be certain Doyle had each of these things as he walked into the darkness of the world. The liver was sweet against the mummy’s mouth, black and heavy within their own hollowed body. But their body grew ever round and full as they pulled the life from Doyle and made it their own.

Pressed into the dirt, the mummy stripped Doyle of his time-worn suit, coins scattering the ground as they flung the trousers away. Doyle’s withered body came to be wrapped within the mummy’s own bandages, centuries of rot binding his legs together, arms crossed over his chest. Within every layer, the mummy carefully placed the man’s coins; a dime in the crook of his elbow, a penny on his tongue.

“It will not matter,” the mummy said, its three tongues slurring the words, “if you take the coins or give them. When they wake you, you will know only the hunger. Death shall come on swift wings to whosoever touches the tomb. Remove no stone or brick. Disturb no grain of sand, unwrap no length of cloth.”

With the wrapping finished, the mummy carried Doyle to the sarcophagus upon the stage and carefully placed him inside. They plucked Doyle’s sobbing eyes from his head and replaced each with a coin: a halfpenny for the left, the gold Tremissis bearing the image of Saint Michael, marked with the mummy’s fingerprint and faience besides, for the right.

§

For a dark bronze disk imprinted with the fading image of Horus, the three-tongued mummy will wake soon after you place the coin in its mouth. Where the coin was placed determined where one went: past, present, future. Before, during, after. Inferno, purgatorio, paradiso.

The mummy will not remember the years that have come before, and will not immediately understand where they are, but the mummy will be bound to you. The mummy will remain with you, however should you provide a body (or bodies, for the mummy will be hungry after centuries of unslaked revenge), they will do the work their heart guides them to.

They will ensure that you will not be without an ancient, withered body to display, given what you paid for their own.