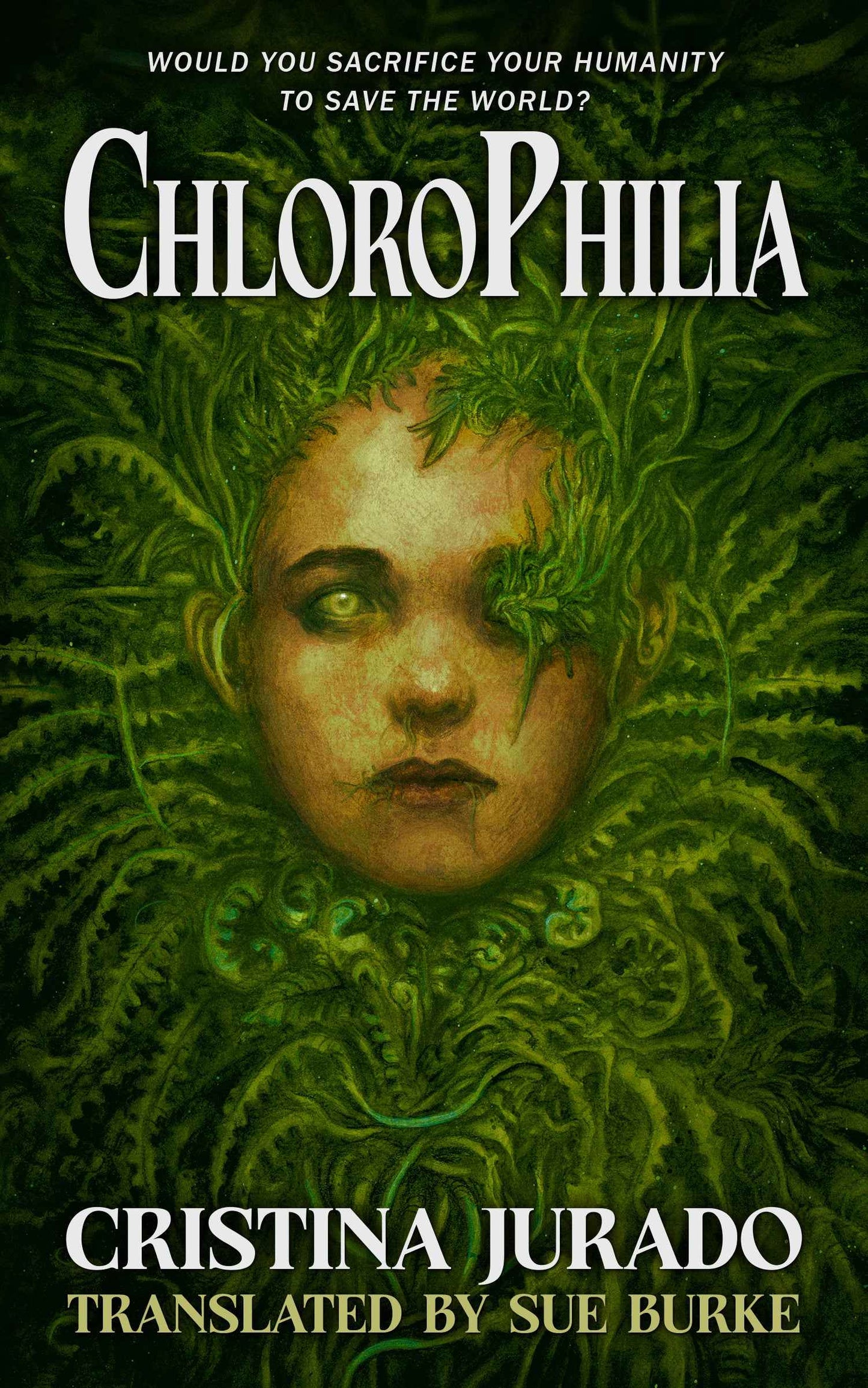

ChloroPhilia

by Cristina Jurado

Cover art by Jana Heidersdorf

ISBN 9781955765244

Pp. 128

Disclosure: We are an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Would you sacrifice your humanity to save the world?

Kirmen is different from the other inhabitants of the Cloister, whose walls protect them all from the endless storm ravaging Earth. As a result of the Doctor’s cruel experiments, his physical form is gradually evolving into something better fit for survival in the world outside.

Kirmen worries about becoming a pariah, an outcast among the other denizens of the domes. But his desire for affection and acceptance, and his humanity, fade away as the Doctor’s treatments progress. What will happen when the metamorphosis is complete? What will be left of Kirmen and the group of survivors that he knows and loves?

In English for the first time (translated by Sue Burke), ChloroPhilia, an Ignotus Award-nominated novella by Cristina Jurado, is a strange coming–of-age story while addressing life after an environmental disaster, collective madness, and sacrifices made for the greater good.

About the Author

Cristina Jurado is a bilingual author, editor and translator of speculative fiction. In 2019 she became the first female writer to win the Best Novel Ignotus Award (Spain’s Hugo Award) for Bionautas. Her recent fiction includes the novella CloroPhilia and her collection of stories Alphaland. Since 2015 she has ran the Spanish multi-awarded magazine SuperSonic. In 2020 she was distinguished as Europe’s Best SF Promoter Award and started to work as a contributor for the bilingual quarterly Constelación magazine.

About the Translator

Sue Burke is the author of the science fiction novel Dual Memory. She also wrote Semosis, Interference, and Immunity Index, along with short stories, poems, and essays. As a result of living overseas, she's also a literary translator, working from Spanish into English for such writers as Angélica Gorodischer, Sofia Rhei, and Cristina Jurado. She's currently enjoying life in Chicago.

Excerpt

The patient tried to sigh but couldn’t through his overlapping lips. He raised his hand to separate them and open his mouth, something he’d have to learn to do by moving the new muscles on both sides of his jaw.

“Damn that wind!” the voice said. “It keeps making me nervous every time it blows that hard.”

He found it hard to answer. “I don’t hear anything, Doctor.” At least his voice still sounded like it used to.

“One of these days, the membranes will fly away, Kirmen. Remember what I’m saying. The wind will carry us wherever it wants. I only hope it’ll be someplace silent.”

The teenager rolled over in his hospital bed. “Have I been asleep for a long time?”

“Several sandstorms.”

“Where are my parents?”

“I suppose they’re getting everybody’s best wishes. I’ve never seen a couple that can fake being together that well. I almost believed that they love each other. Who knows? Maybe this mission really does bring them together. I wouldn’t be surprised. I’ve seen stranger things.”

“When can I go home?”

“You need to let your body get accustomed to this configuration. Close your mouth, boy, I can see all the way to the roots of your teeth!”

“If I close it, I can’t talk.”

“Why do you want to talk? There’s no one here you can give a speech to. Your parents are busy managing your newfound popularity. They won’t be back for a while. They’ll bring glasses so you can use your eyes. Until then, you’ll have to put up with me.”

The young man closed his lips and waited patiently. Fortunately, the old man stayed quiet until the ward nurse brought the glasses, then left without a word.

“Do you want me to put them on you or can you do it yourself?” he heard.

“I helped design them. I think I know what to do.”

Reviews

"Chlorophilia could be viewed as an example of the New Weird genre. Other New Weird books like Annihilation encourage us not to fight the inevitable changeability of the world around us, but rather to embrace it, even if we may not fully understand it. ... While Chlorophilia intentionally leaves many questions open, one point is clear: humanity requires a connection with the natural world to survive."

—Ancillary Review of Books

"ChloroPhilia —an unsettling, enticing novella about evolution in overdrive—is Cristina Jurado's most recent work in English. Like her collection Alphaland, which came out in English in 2018 and then was reissued in 2023, ChloroPhilia offers readers Jurado's unique vision of the world, in which the bizarre and grotesque erupts into the mundane world." —Strange Horizons

Read More from Cristina Jurado

"The Invention of Speculative Fiction in Spain" - Issue 76 of Apex Magazine

"The Many Languages of Speculative Fiction" - Issue 112 of Apex Magazine

Share

- Description

- About the Author

- About the Translator

- Excerpt

- Reviews

- Read More from Cristina Jurado

Would you sacrifice your humanity to save the world?

Kirmen is different from the other inhabitants of the Cloister, whose walls protect them all from the endless storm ravaging Earth. As a result of the Doctor’s cruel experiments, his physical form is gradually evolving into something better fit for survival in the world outside.

Kirmen worries about becoming a pariah, an outcast among the other denizens of the domes. But his desire for affection and acceptance, and his humanity, fade away as the Doctor’s treatments progress. What will happen when the metamorphosis is complete? What will be left of Kirmen and the group of survivors that he knows and loves?

In English for the first time (translated by Sue Burke), ChloroPhilia, an Ignotus Award-nominated novella by Cristina Jurado, is a strange coming–of-age story while addressing life after an environmental disaster, collective madness, and sacrifices made for the greater good.

Cristina Jurado is a bilingual author, editor and translator of speculative fiction. In 2019 she became the first female writer to win the Best Novel Ignotus Award (Spain’s Hugo Award) for Bionautas. Her recent fiction includes the novella CloroPhilia and her collection of stories Alphaland. Since 2015 she has ran the Spanish multi-awarded magazine SuperSonic. In 2020 she was distinguished as Europe’s Best SF Promoter Award and started to work as a contributor for the bilingual quarterly Constelación magazine.

Sue Burke is the author of the science fiction novel Dual Memory. She also wrote Semosis, Interference, and Immunity Index, along with short stories, poems, and essays. As a result of living overseas, she's also a literary translator, working from Spanish into English for such writers as Angélica Gorodischer, Sofia Rhei, and Cristina Jurado. She's currently enjoying life in Chicago.

The patient tried to sigh but couldn’t through his overlapping lips. He raised his hand to separate them and open his mouth, something he’d have to learn to do by moving the new muscles on both sides of his jaw.

“Damn that wind!” the voice said. “It keeps making me nervous every time it blows that hard.”

He found it hard to answer. “I don’t hear anything, Doctor.” At least his voice still sounded like it used to.

“One of these days, the membranes will fly away, Kirmen. Remember what I’m saying. The wind will carry us wherever it wants. I only hope it’ll be someplace silent.”

The teenager rolled over in his hospital bed. “Have I been asleep for a long time?”

“Several sandstorms.”

“Where are my parents?”

“I suppose they’re getting everybody’s best wishes. I’ve never seen a couple that can fake being together that well. I almost believed that they love each other. Who knows? Maybe this mission really does bring them together. I wouldn’t be surprised. I’ve seen stranger things.”

“When can I go home?”

“You need to let your body get accustomed to this configuration. Close your mouth, boy, I can see all the way to the roots of your teeth!”

“If I close it, I can’t talk.”

“Why do you want to talk? There’s no one here you can give a speech to. Your parents are busy managing your newfound popularity. They won’t be back for a while. They’ll bring glasses so you can use your eyes. Until then, you’ll have to put up with me.”

The young man closed his lips and waited patiently. Fortunately, the old man stayed quiet until the ward nurse brought the glasses, then left without a word.

“Do you want me to put them on you or can you do it yourself?” he heard.

“I helped design them. I think I know what to do.”

"Chlorophilia could be viewed as an example of the New Weird genre. Other New Weird books like Annihilation encourage us not to fight the inevitable changeability of the world around us, but rather to embrace it, even if we may not fully understand it. ... While Chlorophilia intentionally leaves many questions open, one point is clear: humanity requires a connection with the natural world to survive."

—Ancillary Review of Books

"ChloroPhilia —an unsettling, enticing novella about evolution in overdrive—is Cristina Jurado's most recent work in English. Like her collection Alphaland, which came out in English in 2018 and then was reissued in 2023, ChloroPhilia offers readers Jurado's unique vision of the world, in which the bizarre and grotesque erupts into the mundane world." —Strange Horizons