She is at the bottom of the trail, and she is going to save her father.

The dirt beneath her soft summer shoes is more like dust. The rocks lining the way have that faded cast of ground that's seen too much sun. Ahead, up the mountain, great oaks and slender birches stretch their soft, green fingers to the broken blue of the sky.

What Noor did today she's done before: left extra food within Papa's reach and told him she's going to trade amaranth grain in the village. Leaned in to let him peck her cheek before she left the house.

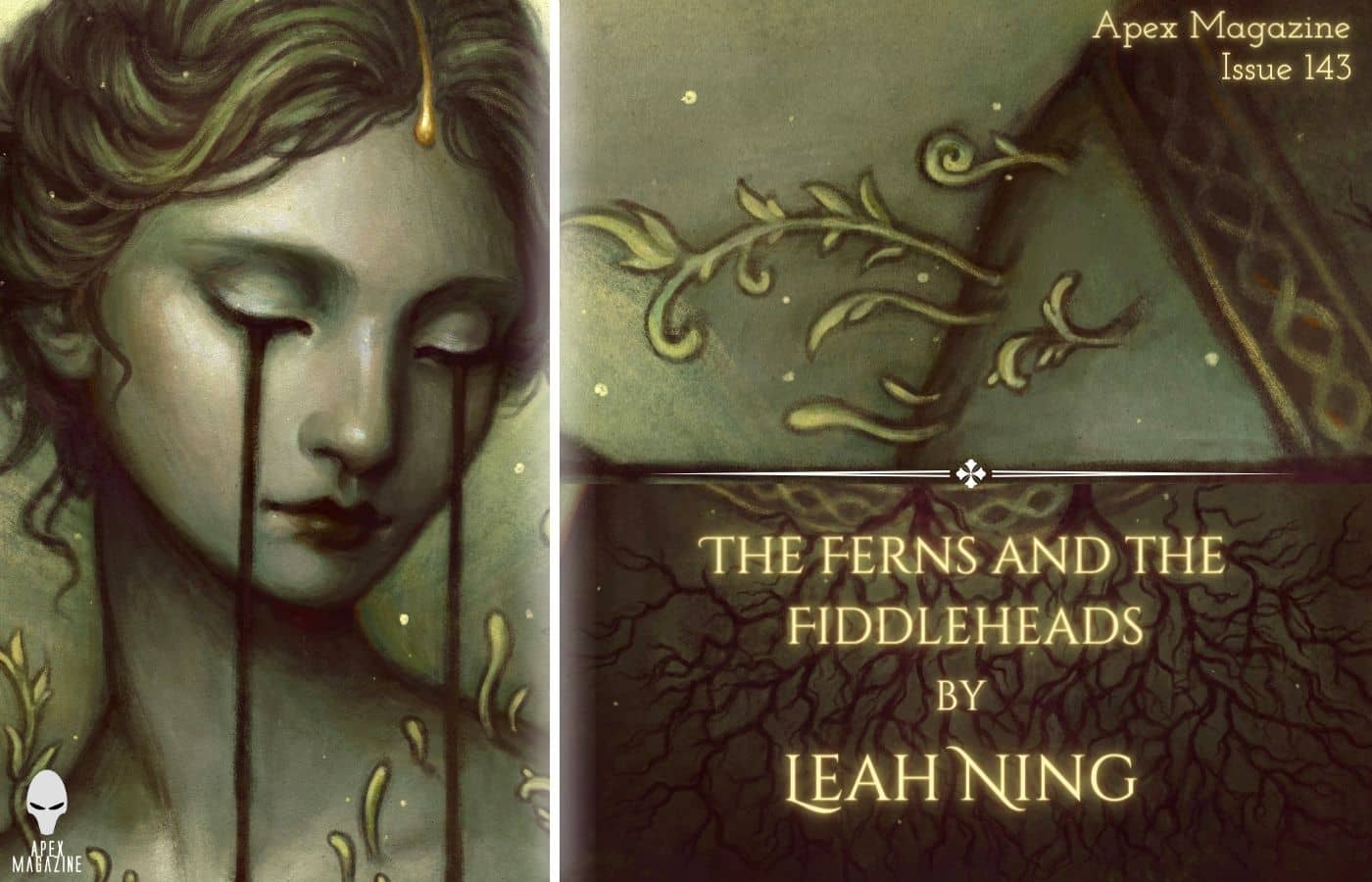

He used to pick falsehood from her face as easy as Mama drew her scythe through amaranth stems in the field, and other villagers always asked her aid come harvest; Fatin Bakir's deft hand sped the work by days. But the ferns have turned Papa's thoughts to slow, ponderous things, moving the way a fighter does just before they hit the ground. Fresh fiddleheads unfurl from his skin each night, bobbing merrily with his breath each morning.

The amaranth killed Mama two years ago, when Papa was still strong enough to stop Noor going up the mountain. Before the first time he couldn't get up without her help.

Now that he can’t stop her, Noor begins to climb with swift, sure steps. The dust of the path settles on the bare tops of her feet, works its way down between skin and cloth and begins its slow abrasion.

There’s big magic at the mountain's top, she hears. Big enough to coax the ferns from Papa's skin before they grow through his tongue, their wet leaves a dark clog in his throat.

When she reaches the dubious shade of the trees, skin cool beneath a sheet of sweat, there's a slim blade of pain between her shoulder blades, small and precise, almost a needle. She draws a breath in through her teeth and reaches back, thinking of a thorn, or—

She is at the bottom of the trail, and she is going to save her father. Standing next to her is a boy.

He looks at her strangely, this boy stuck between the child he is and the man he'll become. Fatin supposes it's not truly strange—girls know want when they see it, even before womanhood—but it's strange from him. It would be easier if she loved Warren the way he wants her to.

He offers his hand. An offer, not a demand; she sees it even through her terror of the mountain, which chews up those who brave it and does not spit them back out. She's heard it snatches you up with thorny, brittle fingers the moment you're out of sight. She's heard stories of screams. She's heard it devours you slow, nestles its teeth in the soft of you so you don't know it until it rends flesh from fat, fat from muscle, muscle from bone.

Fatin is counting on that last one. She's also heard that the higher you climb, the more magic you get, and she's not taking any chances.

She accepts the offered steady strength, and the smile he produces warms the sweet brown of his eyes.

Noor’s fingers close on the velvet of new leaves. The vision of her Papa drains away while she traces the leaves' edges to their stem, the stem down to the split skin between her shoulder blades.

They were here. Noor watched Mama come to save her own father, and Papa came with her ... for what? For love? To keep her company? Both, probably. Noor never knew him that young, but she knows his eyes. They are the same ones that peered up at her, dull and fuzzy with pain, when she left him that morning.

"You left enough," he said, "for two days." Those eyes flickering to the food at his bedside, then back to her.

Had he known? She didn't think so. "In case of calamity," she said, smiling, and left as he laughed. Left before his laughter could get him to coughing. She thought she'd scream if she heard him cough again, the roots tracing delicate madness on the insides of his lungs.

Now she's got her own roots. None in her lungs, not yet, but the feeling of wrong as she tugs that stem—thin little seedling-filaments in her spinal column, threatening to snap—jolts her stomach.

She turns back, one soft shoe scraping a slim fan into the dust. Her fingers tremble at the split in her skin. She can't see the bottom of the path anymore, not even the opening in the trees. She'd just entered them, hadn't she? But her feet ache like she's been walking for hours. Walking while she lived her Mama's memories, maybe.

She could go home. Maybe should. The mountain's wound its green and pliant fingers through her skin.

But is it enough?

She looks up the dusty trail. The air hangs thicker up there; sweat winds down her face, tickles at her ribs. If she climbs and doesn't return, she won't forgive herself. If she doesn't come home with enough magic to coax the ferns from Papa's skin, she won't forgive herself.

Because she loves him? Because she can't listen to him cough anymore without her chest tightening down so hard she can't breathe? Because she's afraid that one morning she'll find him purple and choking on dark, wet fronds, reaching for her, hoping she'll know how to save him?

Noor begins to climb again. She doesn't know how to save him any other way.

Her fingers close on the velvet of new leaves. Warren brings his hand to hers, and he's not so steady anymore, watching the slow, dark run of blood over the deep brown of her bicep. An acorn tat-tat-tats its way down through the canopy to thunk down into the dust somewhere behind them. Fatin runs a finger down the soft edge of one leaf, down to where the stem swells the split in her skin.

"You, too?" she asks.

Warren shakes his head. He's trembling. She wants to and cannot quite reach for his hand again. He won't look at her, the way she can't look at her Da sometimes when he's wheezing his way through one of his episodes, the heel of his palm pressed to his sternum.

Fatin's belly sends up an anxious flare. She isn't dying. She needs him to look at her.

"Why?" she asks.

"I don't know." Still with those trembling fingers at her knuckles, still with downcast eyes. "Maybe ... I didn't come here ... wanting it. Like you did."

Gods, she hopes so. She can feel more beneath her skin, stirring, beginning to unfurl. He came to be with her, not for this slow annexation of the body by strange, deep magics.

When Fatin pulls away and begins to climb again, he catches up with her, nervously massaging at one lean forearm. He does not offer his hand. She does not offer hers.

He's lying. She knows it.

Noor plants her feet in the dust, trying to swim through the daze of her thoughts to grasp the why. It is still high noon, desert-hot even in the shade. Her head swims, and her skin hurts, but she knows her Papa was lying.

When Noor was little, she clipped golden bouquets from Mama's hair. Papa's skin was still clear then. Noor stopped clipping when the severed stems wept red instead of clear, sticky-slippery sap.

After that, he never had time to go up the mountain. Mostly he sat with Mama, his thick, strong fingers in her hair, working at her scalp, easing the ache of the roots.

His ferns showed up after she died. Not in ones and twos, the way Noor's sprouts are—she's got another in her palm now, roots sunk into the meat of it, blood a warm and steady drip from the tip of her middle finger—but all at once, a thickening bed of them in the rotting garden-flesh of his body.

He clipped them, must have, all the way down to the skin. Hid them from Mama, from Noor.

She supposes she could ask why. She's never known her father to lie. It could be something as simple as not wanting to worry Mama. Wanting to care for her, especially in her final days, those dark hours of viscous blood and deep, curdled gasps that made Noor's insides shrivel.

She breathes in dry, thin mountain air. The drip of warm red from her fingertip does not stop, but slows.

Go home, Noor. You've got enough. You don't know how long it's been and Papa's waiting for you, so go home.

She doesn't want to. Out here she's doing something. Out here there's an answer, finally, to the constant molten roll of terror she's lived with since she can't remember when.

Out here she might come back and find Papa dead, but gods, she won't have to watch it happen, figure out what to do, wonder if she could have done better, if she could have saved him.

Out here she can save him.

If you're out here to save him, go home. You've got enough.

She can't know that. There's no way she could. So she has to keep going, to let more magic take root, to climb all the way to the top even if she has to crawl.

Doesn't she?

He's lying.

He says he's not afraid, but Fatin can almost smell it on him, a sharp-sour humidity that hangs in his wake. Afraid of what the mountain is doing to her? Afraid of what she's doing to herself? She doesn't suppose it matters.

She's losing time. The sun doesn't move, but she hurts more than she should for the time she's been walking.

"Quiet," Warren says when Fatin asks how she seems during these lost stretches. He wipes his damp palms on his pants. It's not a habit she's noticed before, but has she ever seen him out in the sun this long, sweating this hard? She doesn't think so.

Her first seedling has grown up toward her shoulder. Another has unfurled at her temple and, as she walks, its leaves brush her ear like light insect legs. The blood it brought dripped from the point of her jaw, slowed, stopped, became a crumbling rusty streak.

Warren walks with his head down, steps sliding in the dust, hair wet and clinging to his head, one glossy, dark curl stuck in a lovely whorl at his temple.

Fatin's hand drifts toward his as if by gravity, magnetism. And, cautious hope pulling his brows together, he takes it.

The next seedling bursts through the soft underside of her jaw. Movement there, like a questing finger, and then it comes through in a glut of jellied red that sticks, quivering, to her shirt, her pants. Noor gags, which pulls at the roots anchored in the tender flesh beneath her tongue, and she swallows hard. She wants it out, hates the way it seems to subsume her, but she stills her restless fingers.

There's a bud at the tip of the seedling in her palm now. Fingernails of red show through the fat teardrop of green. She's curious, somehow, as to what it'll be. Golden amaranth for Mama, ferns for Papa; what of the mountain does Noor relinquish her flesh to?

She swallows again, feels that deep tug, gets a brief but brilliant sear of panic from her belly.

She thinks, with a low, sick feeling, of how sometimes she stays at the market longer than she really has to. Sometimes it gets her a better price for their amaranth grain, sometimes it doesn't. More often it doesn't. Those days she comes home with hard, hot guilt in her throat and what if, what if, what if pounding sick headache drums behind her eyes. If she left for too long, or at the wrong time. If she came home to that dark, wet clot of leaves in Papa's throat.

The more it turns out okay, the more often she does it. She never feels so alone as when she's with Papa, caring for him, responsible for him, listening for those thick, hitching breaths that might mean he's asleep or might mean she's got to go weed out his throat.

Is this one of those days, where she's convinced herself that it'll be better if she stays a bit longer? That she'll get more magic for her time, surer cure for the risk? She doesn't know, but in her daze of blood loss, she dreams of the mountaintop, of ripping through the dust with her bare hands, of pulling out what magic she finds there and bringing it home, of saying This is for you, I did this for you, for you, for you.

The next seedling bursts through the soft underside of her jaw. Fatin gasps, and Warren's arm is around her shoulders, solid and warm. Her hand fills with the slippery heat of her own blood. And now she's shaking, but he's steady, holding her tight against his side. For a wonder, she is not uncomfortable, but grateful.

"Isn't this enough?" he asks while the dust takes the liquid rubies she provides with greedy gulps.

She shakes her head. If he'd told her it was, she might have believed him. But he asked. He isn't certain. So she has to go on. And he goes on with her, still wiping his palms on his pants.

She gains the summit with the final scum of energy she's dredged up from her exhausted insides. Her palm has bloomed: a red poppy, first nodding with the wind of her passage, then crushed into the dust as she falls, then lays, panting, on her side.

Gods, it is so hot.

It's treeless up here, the sun still baking down on her from directly overhead. Noor turns onto her back, chest heaving—there's a poppy nodding merrily there now too, she notices—and lets her fingers slip beneath the dirt—

Mama at the top. Papa catching her, trying not to fall himself, trying not to let her feel the growth beneath his shirt—

Mama's fingers in the dry dirt, Papa reaching—

Papa's want for her, the unyielding desperation of it—

Mama's love for him, not the same, not the same desperation but changing, yielding beneath Papa's fingers, growing into something almost as alien as the amaranth tucked behind her ear—

The way they kissed when they reached the bottom, the way it was Mama who took his face in her palms, knowing she couldn't have done it this morning, and, gods, her relief—

Noor can't stop it this time. She scrambles over onto her side and vomits. There's that deep tug beneath her tongue, now winding into her throat, and she gags again, brings nothing up.

He made it happen. He made Mama love him. He'd led her to the cliff and pushed her off and called that falling.

And Noor. She shouldn't even be alive, not if Papa hadn't—

"Oh," she says into the blistering silence. This time the sick feeling goes deeper than just her guts. She's sick down to her soul and she hates him but she can't, not entirely, not the man who tickled her face with red feathers of amaranth while he carried her through the fields on one hip, the man who laughed every time she tickled him back, only able to reach the crease of his elbow.

She came out here to save him. From what he did to himself. From what he did to Mama.

Noor pulls in a slow, deep breath. She raises her arm and reaches back, back, feeling between her shoulder blades until her fingers close on velvety petals, slick leaves, fuzzy stem.

What Papa's taught her: you can't yank a weed from the ground and expect to pull all its roots. Even through her shortening breath, Noor knows this, has learned it over the years of cultivating the amaranth fields. You have to pull with gentle, constant pressure, moving side to side, feeling where the roots will consent to come loose and where they threaten to snap. If they break, the weed will grow all over again. If they break, they'll keep spreading, anchoring themselves in the dirt as if to spite your efforts.

And she wants them gone. The poppies, the memories, the new and half-panicked disgust for her father, gone all the way and for good.

So she doesn't yank the poppy out. She puts gentle pressure on it, holding the stem tight and close to her skin, wiggling back and forth, feeling the roots sliding and tugging at her spine. Her breath comes out in high-pitched gasps. Her skin, beneath the constant beat of the sun, is cold and rough with goosebumps.

And then the pain comes like lightning, shooting up through her neck and down to her fingertips and toenails. Noor's throat closes up so tight she can't scream. Something between her shoulder blades tears, and she feels the poppy pull free of her skin with the familiar weight of a weed with dirt clumped in its roots.

Panting, she throws the flower and its roots behind her without looking. She presses her forehead into the dust. The newly empty spot between her shoulder blades throbs. She still remembers everything, all of it. She wants it gone. Even the magic. She wants it out of her down to the roots. She wants to go home.

Noor drags herself to her feet and eyes the entrance to the path. As she steps back into the trees, she takes gentle hold of the stem in the soft underside of her jaw, as close to the skin as she can grasp.

Noor's dizzy and shaking by the time she reaches the feathery red fields by their little log house. She's rid of the poppies, empty throbbing holes in their place, but there are more beneath her skin, growing, curling, preparing to tunnel their way free.

He's in there. Behind that door, down the hall, laying in his bed, waiting for her to come back. She was terrified that she'd be gone too long, afraid she was selfish, and for gods' sake time didn't exist on the mountain. The sun hadn't moved a tick when she left the tree cover.

And still she's going to save her father.

Because she wants to hate him. Because she shouldn't exist. Wouldn't, if he hadn't done an unspeakable thing to her mother, a thing that lasted the rest of her mother's life. Because he deserves to live without what he'd wanted so badly he'd taken her mother's autonomy, her choice, and molded it to fit his desperation. She hoped it would destroy him. She hoped he'd live long, long after she died, knowing what he'd done, knowing she died hating him.

Even though she doesn't. Wants to and doesn't, at least not all the way. Can't, no matter how she tries. Even with magic.

Noor goes inside. Once, burning with guilt, she might've softened her footsteps, hoping he'd sleep, give her a little more time to rest. She does nothing of the sort now as she goes to the doorway of his bedroom.

"Hey, Noor-girl," he says in his tired, raspy voice.

She presses her lips together until it hurts. The empty place below her tongue wakes and sings its rusty sawblade song. The floor is falling out from under her. She never wants to see him again. She wants to see him cry, hear him beg her forgiveness, watch his face as she refuses to give it. She wants him to crush her to his chest and explain it all away and make it gone.

Papa's face drops the way sticky sap might fall in winter: sluggish, halting, then all at once. "You went. Oh, baby girl—"

"Don't," Noor hears herself bark. Her tongue is no longer hers. "I know what you did to her. I saw it, the mountain showed me. I felt it, you bastard!"

His eyes flick up to the ceiling. His mouth tightens. "I know."

"You don't! You—"

"I couldn't leave it."

"You could have!" Noor's shouting now, her voice overfilling the little space. "You could have let her be!"

"I took it back," he says.

She can't listen to it. If he did something right, tried to fix what he did, she can't make herself hate him. He's lying, he's lying, he's been lying longer than you've been alive. "I don't believe you!"

"I know."

Noor's anger cools. It doesn't go. Just cools into something smoldering, calculating, beneath the raw skin of her chest. She goes to him without speaking and lays her palms against his stubbled cheeks, presses her mouth to his burning forehead.

"It's okay," she whispers, and reaches for what the mountain has given her. What it's invaded her with. What she's taken. Her father's sweat chills on her lips. "You're going to live."

She feels it wake within her, the magic she found at the summit, and—

It's leaving her. That sear of panic comes to her again, brilliant but less brief.

"No." She tries to jerk back. His hands, those thick, strong fingers, hold her in place, wrapped tight around her biceps. "No, stop, stop—"

But it's draining, all the seedlings, the roots, the new-made leaves, not shrinking but leaving, passing from her to him as she struggles against the pure, thick bed of magic the mountain sowed in him more than her lifetime ago.

And hers is gone. Her bones feel hollow, her muscles soft and shaky. She feels oddly bereft, furious, exhausted. She wants to hit him, to scream at him, and instead she says helplessly: "You weren't supposed to."

"You do not deserve to die," he says, "for what I did."

Noor searches the soft, somehow unfamiliar brown of his eyes for a lie. Wanting to find one. To find something that means he's wrong, that she can safely hate him.

She finds none of it. Her face drops into the garden of fiddleheads and poppies that is his chest, and she begins to cry.

When Noor wakes the next morning, she's in her own bed and he's gone. His bed is empty, and so are the fields when she scours them. There are footprints in the dust by the mountain's base, big shuffling ones, and she thinks of following them—he can't make all her choices, can he?—but goes home instead.

She cleans the dried and rotted leaves from his bed. She washes the sheets and hangs them to dry while she turns the mattress. She replaces the feathery red amaranth by his bedside with gold clipped from Mama's grave in the fields.

When she goes to bed that night, she replays those moments in her head. The feeling of his magic beneath her skin, pulling up roots, digging up seeds. Trying to remember if she felt anything else, any of his magic changing her the way he changed Mama. Because Noor still can't make herself hate him, and gods, it would be so much easier if that was his fault.