You are happy.

You are healthy.

You take good care of yourself.

But you could be happier. You could be healthier. You could take better care of yourself. If you really wanted to. So sayeth the wellness industry (mileage may vary). And the more unhappy, unclean, unhealthy you are made to feel about yourself, the more likely you’ll buy into whatever it is that can make you happy, clean, and healthy … this month. I’m not knocking the wellness industry, or at least not all of it. What I’m knocking is how the wellness industry and wellness culture have become twisted. How they, as Rose Keating puts it, “benefit from our self-loathing.”

When wellness magazines or advertisements recommend something absolutely outlandish, how many of us laugh and say “that’s ridiculous,” and how many of us sign up for it in hopes that it will work? That we’ll finally be happy?

In Rose Keating’s story “Next to Cleanliness,” Catherine wants to be healthy and happy. A cleanse from Dr. Matthews’ office worked for her friend, so certainly that will work for Catherine as well, right? And what won’t she do to be happy and healthy?

She thinks she’s going to be prescribed weight loss pills or a strict exercise regime for rapid weight loss. Dr. Matthews is strict, and his treatments are straight from a horror movie. But then everyone compliments Catherine’s rapid weight loss! Until the weight literally doesn’t stop melting off. Not satisfied, the doctor tries additional treatments because, in his view, Catherine still isn’t happy or healthy. But she could be if she really wanted to be!

A combination of body horror and passivity, “Next to Cleanliness” feels like a perfect episode of The Twilight Zone, an episode that flirts with satire.

Keating’s work has appeared in Hot Press Magazine, Southword, Banshee, and The Incubator. She is the winner of a Sean Dunne Young Writer’s award and won the Hot Press Write Here, Write Now competition. She is currently working toward an MA in Creative Writing at the University of East Anglia.

In this interview we talk about what was behind “Next to Cleanliness,” the wellness industry, writing about uncomfortable and taboo feelings, permission to try something new, and that it’s okay to not always feel empowered and strong.

Not feeling strong today? Not feeling happy? It’s ok. You’re ok, no matter what the wellness industry is trying to sell you this week.

Editor’s Note: Beware spoilers!

APEX MAGAZINE: What inspired this story? What kinds of things were you thinking about while writing it?

ROSE KEATING: I started writing this story in January 2020, over the Christmas break before I returned for my final undergraduate semester. I had been mindlessly scrolling on my phone and advertisements for New Year’s cleanses kept cropping up, which was gradually driving me a bit madder each time. But then something clicked in my brain, and I realized the cleanse idea could be a lot of fun to play within a story. I have a complicated relationship with cleanses as a concept; on the one hand, they’re representative of a fairly cruel, problematic overlap of patriarchy and capitalism—of the ways society actively encourages us to dislike ourselves and the ways it benefits from our self-loathing. It’s an intersection that results in the moralizing of happiness, while also setting standards for happiness that are never truly achievable since these standards are in constant, deliberate flux.

On the other hand, there is something deeply seductive about the idea of being able to become a brand-new person overnight. Being able to become a good, happy, clean version of yourself magically over a few days or weeks; it’s a lovely kind of fairy tale. While I was working on the piece, I was thinking about those two clashing ideas the most; the cruelty and falsity of wellness culture as well as the beautiful, seductive nature of what it promises.

AM: Catherine could have visited any health guru in the city. What’s the real reason she chose Dr. Matthews?

RK: I don’t think Catherine is necessarily the most independent or assertive person, so I doubt she would have sought out any doctors or health gurus at all if her friend, Susan, hadn’t suggested it to her. I imagine she probably chose Dr. Matthews purely because it’s what her friend told her to do. I’m quite interested in passivity in characters and particularly what it means to feel passive as a woman, so I think Catherine and the nature of her choices is probably a continuation of that theme.

AM: There isn’t much many of us won’t do to be happy. To be clean. To be thin. What does Catherine hope to get out of her visits with Dr. Matthews?

RK: It was important to me that Catherine’s reason for seeking out Dr. Matthews wasn’t something completely singular or specific. She feels down and is aware that she isn’t happy in the way we are told happiness should be or should look like. When I was writing the first draft, I briefly thought about shoving in a specific source that created this feeling, but something about that felt a little cheap and reductive. It’s tempting to try and attribute all unhappiness to specific events or individual traumas, to medicalize and sanitize it into a specific, solvable problem—but the reality is that a lot of people are unhappy and there isn’t always a singular, easily solvable reason for that feeling.

I don’t think it would be outlandish to suggest that Catherine has a sense of herself as lacking in terms of happiness or wellness because society actively encourages her to feel like she is lacking while, simultaneously, criticizing her for that feeling. She lives in a world that encourages and profits off her unhappiness then shames her on an ethical level for being unhappy. Living in a world like that would probably be enough to make you feel like you need to go somewhere to be fixed, and she goes to Dr. Matthews because on some level she wants that for herself.

AM: All the different therapies that the doctor tries for Catherine—to rid her body of toxins—how did you come up with those? Some of them are quite creepy!

RK: I honestly wish I knew! Coming up with ideas is probably one of the things I find most frustrating about writing. Not because I have none, but because it can feel like something that isn’t entirely in your control or that can’t be reduced to a step-by-step process. I’m a big believer in thinking of writing in a practical way, in terms of craft and nuts and bolts: solid, pragmatic elements that can be understood, tools that can be improved. Viewing writing through a dreamier, more artistic lens makes me a little nervous because it feels almost mysterious and uncontrollable. It makes inspiration and creativity feel a lot more random and esoteric, which might come across as romantic but is equally kind of terrifying because it’s uncomfortable to acknowledge that lack of control. The therapy ideas came to me like that: just randomly. I have a big, rough notebook that I use to write down lists of possible scenes for stories, and I mostly just brainstorm them as I’m going and pick the ones that feel the most relevant or interesting thematically, so I suppose that’s the closest I come to a process for that.

AM: As I was reading, I expected the story to end when Catherine does all the classic “how to be happy” stuff, like journaling, volunteering, practicing gratitude, meditating, and such. But no! Dr. Matthews wants to try one last therapy to cure her of toxins. Why not end the story when Catherine appeared to have found happiness?

RK: I suppose for me, the reason it didn’t end there is because she hasn’t found happiness at all. She does all the correct things, yet she still feels that lack inside of her. A lot of Dr. Matthews’ therapies revolve around the implication that Catherine is unwell/unclean/unhappy because she is not trying, or because she is doing something wrong.

Her toxicity is viewed as self-inflicted; not only does Catherine feel bad, she is also encouraged to feel bad for feeling bad. According to the standards set by people like Dr. Matthews, this feeling is her own fault and if she only does the right thing this feeling will go away, and she will be as happy and good and clean as everyone else.

Of course, this logic is unkind and flawed, and the point of that section was to address this flaw. Catherine plays ball: she follows the steps, she does all the things she is told will make her better, and yet she is the same person at the end of this, still trying to figure out how to feel as happy and whole as everyone else seems to feel. I decided I couldn’t end it here as it was almost a little too hopeless. While the actual ending might not be viewed as wholly positive, it felt like a way to offer Catherine more than this, to move beyond this restrictive logic and embrace something different.

AM: What are some of your favorite themes to write about? Why do those themes fascinate you?

RK: I’ve spent the past year on the University of East Anglia’s Creative Writing Prose Fiction MA where I’ve been working toward a short story collection, so I’ve been thinking about this question a lot throughout the semester. I still find it difficult to answer! With short stories, it seems like each one is its own individual thing, so trying to summarize them all as a collective whole can be challenging. Most of my work centers around the lives of women, so I think it would be fair to say one of the most common themes I return to is womanhood, at least in a loose sense. When I started writing I thought this had to mean a specific thing—that if I was writing about the experience of women, then every story had to be empowered and feminist and follow a positive, explicit ethical and ideological framework. I quickly realized this was not only a bit didactic, but also felt untrue; I don’t always feel strong and empowered and positive, even if I am a feminist, so it felt dishonest to write stories that only focused on that particular narrative. I’m a lot more interested in writing about feelings that are uncomfortable, things that are difficult to give voice to but that linger and haunt.

Because of this, I would say a lot of my stories center around ideas of shame, passivity, and taboo. I think non-realist modes of body horror and the fantastical are great for getting to the emotional truth of difficult, intimate feelings like shame, guilt, grief, anxiety, unruly and transgressive desire, so I’m really enjoying exploring those themes in my collection. With “Next to Cleanliness,” it was interesting to not only write about the societal aspects of self-loathing but also try to write honestly about what it really feels like to think there is something deeply, irreparably wrong with you. There’s something very exciting and satisfying about giving voice to feelings that can be hard or feel shameful to express, so it’s been wonderful engaging with those particular themes with the collection.

AM: When did you decide to become a writer? How has your process and your approach changed over time?

RK: It’s a little cheesy, but I’ve never wanted to be anything else. I genuinely can’t remember a time when I didn’t want to write. This has less to do with a noble commitment to artistic pursuit and more because I’m really bad at everything, and writing is the only thing I’ve ever been a little less bad at. My mum is a big bookworm and owned about a billion Stephen King paperbacks that my brothers and I were allowed to read when we were far too young. Because of this, I was reading at a higher level fairly early, which meant I was okay at writing for my age. Which meant my English teachers were nice to me. Which meant I wanted to write more and more.

Almost everything about my process and approach has changed over the years. When I was a teenager, I only wrote poetry, and I was an awful poet. Around the time I went to university I realized this, and that’s when I began moving toward prose. I took some very bad approaches with prose at first. I was writing short stories, but I had never even read a short story collection before. I was a little dismissive of the form in the sense that I just thought of them as very brief versions of novels; I didn’t understand what the short story form could do at all. I was also trying very hard to sound intellectual so there was an abundance of purple prose and pretentious stuffiness going on. I wasn’t really comfortable with my voice yet and was attempting to copy writers I admired at the time but doing it very badly. I hadn’t quite figured out my process yet either, so I was trying to do the usual things like writing early every morning in the library and that wasn’t working for me. I was a bit nervous working with non-realism at the time as well, as I wasn’t great at writing traditional genre pieces, like hard sci-fi or Tolkienesque high fantasy, but also seemed to be bad at strictly realist literary stories. Basically, I just didn’t really know how to develop my ideas.

My process and approach rapidly changed once I began to grow more comfortable with myself as a writer. I realized I loved writing alone in my room at 3am, and I liked doing a few thousand words in a night once a week, rather than a few hundred every day. I took modules on horror and other modules on post-modernism and began to understand the different modes formally a bit more—I realized that I was able to dip into different genres and modes and take what I needed rather than feeling like the stories had to fit into one particular strict box. I realized that I didn’t have to feign a flowery, intellectual voice and could write in a way that felt natural to me; shorter sentences and a little playfulness wouldn’t automatically make it silly or dumb. I also read a short story collection for the first time, and this changed the way I thought about writing and reading in a fairly mind-blowing way. Things were a lot better after that.

AM: Who are some of your favorite writers? How has their work impacted you?

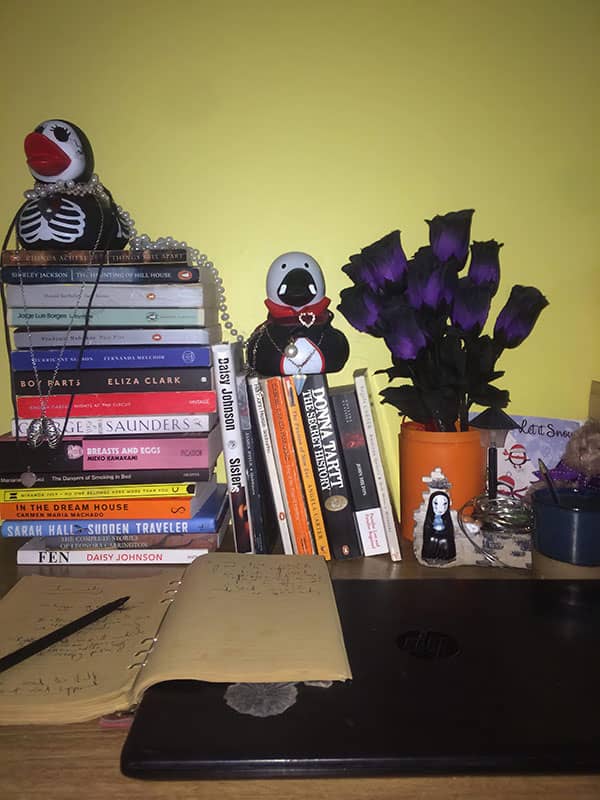

RK: Where to begin! I’m obviously a big short story lover and am a huge fan of writers like Donald Barthelme, Miranda July, Lorrie Moore, Denis Johnson, Camilla Grudova, Leonora Carrington, Clarice Lispector, George Saunders, Raymond Carver, and Carmen Maria Machado. As an Irish writer, I’m lucky to have a lot of writers back home that I admire an awful lot like Cathy Sweeney, Nicole Flattery, and Eimear McBride. Other writers I really love would be Daisy Johnson, Max Porter, Angela Carter, Han Kang, Eliza Clark, Kathy Acker, Sharon Olds, Shirley Jackson, Sophie Mackintosh, and Fernanda Melchor.

Those writers (and so many other) have probably each impacted me in their own way, but one of the writing tutors at UCC once asked me a very helpful question, which is how I now like to think about it. We had to read different pieces each week and answer questions on them, and one of the questions was “What has this piece given you permission to try in your own work?” I don’t think it’s very smart or fruitful to try to be the same as other writers, but this is a lovely way to think about the impact and influence other writers have on our own work—they widen your own understanding of what writing can be and allow you even more freedom to explore new ideas and methods yourself. In essence, the work of each of these writers gave me permission to allow myself to try something new.

AM: Thank you so much!