“Liecraft” is a layered story of fascinating relationships, deception upon deception, and a dynamic environment of buildings and walls that crumble and rebuild in reaction to the characters. To maintain a stable city, where residents are safe from falling structures and from the world of decay and entropy outside the walls, the best architects must practice a level of deception that can take years to plan and set up, and an earthshaking moment to execute.

About the author: Born in 1989, Anita Moskát studied biology and worked as a fiction editor in Hungary. She has published four fantasy novels and a short story collection. Skin and Hide (Irha és bőr) won the 2020 Péter Zsoldos Award, Hungary’s top prize for speculative fiction works. Her work often deals with the oppression of marginalized groups and class and gender dynamics.

About the translator: Austin Wagner is an American living and working in Budapest as a HU-EN literary translator. His translations run the gamut from speculative fiction to contemporary prose and poetry to children’s literature, and you can find his work at Asymptote, The Continental Literary Magazine, Versopolis, Weird Fiction Quarterly, and Hungarian Literature Online, where he is also co-editor.

Marissa van Uden: Thank you both for joining us today to talk about this truly amazing story, “Liecraft.” This was such a great read. My first two questions are for Anita: This story unravels itself in a beautifully fascinating way, with revelation after revelation building up to the fantastic ending. What were the challenges of writing such a nested story, and did it go through many iterations to make sure the reader always has just the right amount of information, to hide certain truths and reveal others at just the right moment?

Anita Moskát: It was definitely a challenge, because I don’t always write stories with these sorts of layers. I like when a story’s theme shows up in the structure of the text, when the form and the theme reflect on one another, so I didn’t really have a choice: I had to lie to the reader. Lies within lies within lies … and only at the end do we arrive at the truth. I wanted the discovery of the truth to be painful, but also liberating, as is usually the case with truth. In order for this to work, I couldn’t allow myself to be any more knowledgeable than the reader. I don’t usually plan out my stories in advance, I discover them alongside the characters. All I knew was that there would be lies and betrayals; I didn’t know where or how. In this sense, I’m walking down the same emotional path as the reader—I have to be surprised too. There are plenty of edits required after the first draft, fine tuning which information goes where, but by then the story already has its heart.

Anita: My best ideas come when I take long walks.

MVU: What inspired this story? Do you remember how the idea first formed, and where it went from there?

AM: The idea first appeared as an image: somebody wanting to share something important, but it’s so difficult to get the words out they start gesturing instead. The truth can be monstrously difficult to speak. We do so much to avoid it, but in the end we can never escape it. I wrote this short story in 2018, and it was the first time I’d broached these themes, but since then, lies and deception have been central to a lot of my work, including my short story collection. I’m interested in how we can use the tools of speculative fiction to talk about the post-truth world. As if we exist in a parallel universe with parallel truths. We pick and choose the facts we want, articles from different news sources give us contradictory accounts about the same event, and now AI is making everything even worse, we can’t decide if news is real, conspiracy theories spread at the speed of light. We’re not living in the same truth, and I find this shocking, I have to write about it.

MVU: This question is for Austin. Some of my favorite moments in “Liecraft” are when the characters are unwittingly revealing subconscious truths about themselves, known only by the way the environment reacts. What were some of your favorite moments or scenes to translate, and why?

Austin Wagner: The puzzle I enjoyed the most in this story was actually finding the right title. A literal translation of the original Hungarian would be something like The Master Lie, and that phrase does find its way into the story, but as a title in English it felt at best too restrictive, at worst like a cheap spy thriller. I wanted something familiar enough that a reader would immediately get a sense of what the story contains—lying and duplicity in spades, every word needing multiple grains of salt to digest—but also something uncanny, a bit jarring, to make it clear this isn’t just deceit in the sense that we understand it in real life, but deceit as an industry, as the literal bedrock of society, as something to be learned and honed and inflicted on others. I think Anita said in an email something to the effect of “it should be weird,” and I’d say we pretty squarely hit that target.

As far as the actual story, I’m smitten with the first sentences Khao speaks. Not only is it the climax of the story, but the reader now knows everything. Which means they know that every sentence he utters is a brutal, vicious, agony-inducing lie years in the making, and the catharsis for the reader is immense, they no longer have to wonder. The simplicity of those sentences, their directness—“It’s alright. It’s not your fault. The masters are still proud of you.”—is emotionally crushing, and after having to very carefully check and recheck my translation to make sure no accidental lies (or truths) slipped in where they shouldn’t, it was fun, if a bit sadistic toward poor Minna, to translate these bits in the most straightforward, no-holds-barred manner possible.

MVU: Amazing to get these insights into the art and science of the process. What have you learned about writing and storytelling by having your work translated, or by translating the works of others?

AM: I always knew translation was complex, involved work, but it’s really something to see it happen to my own texts. The most exciting part for me is the linguistic worldbuilding, how made-up words in Hungarian are brought to life in a foreign language. The translator has to create new words following a similar logic the author used to create them in the first place. Austin is wonderfully creative, and I love getting glimpses into his mind when he explains why he chose a certain phrase, or what other words he suggests as alternative options. The title of this story, for example—“Liecraft”—is far more exciting than the Hungarian title. I have a weird short story that features linguistic horror, and part of the chills stems from the fact that the character doesn’t understand scientific language; the text resembles real language, but is actually just gibberish. It was a funny experience writing it, but I have no idea how it could be translated, it would almost have to be completely rewritten. Translators are magicians.

AW: It sounds kind of stupid, but I never appreciated the intricacies that went into writing before I started translating. Sure, as a rabid reader I probably unconsciously recognized there was more going on than just the story, but as a translator, I now have to become consciously aware of those things. How three particular adjectives over a span of twenty pages are crucially important, how a phrase uttered once on page 3 comes back on page 274 and has to hit with the weight of a wrecking ball, how pacing within a sentence matters just as much as pacing of the story, or how no one text can (or should) contain everything; you need to find what’s right for this story, not take your favorite one-off ideas (or in my case, fun words I love using) and cram them somewhere they don’t fit.

More than anything, I’ve learned that if I’m not counting the pages as I work through a translation, if my eyes never flick to the lower-left corner of that Word doc, it means the text is really singing. And I don’t think I’ve ever known what page I’m on when translating one of Anita’s stories.

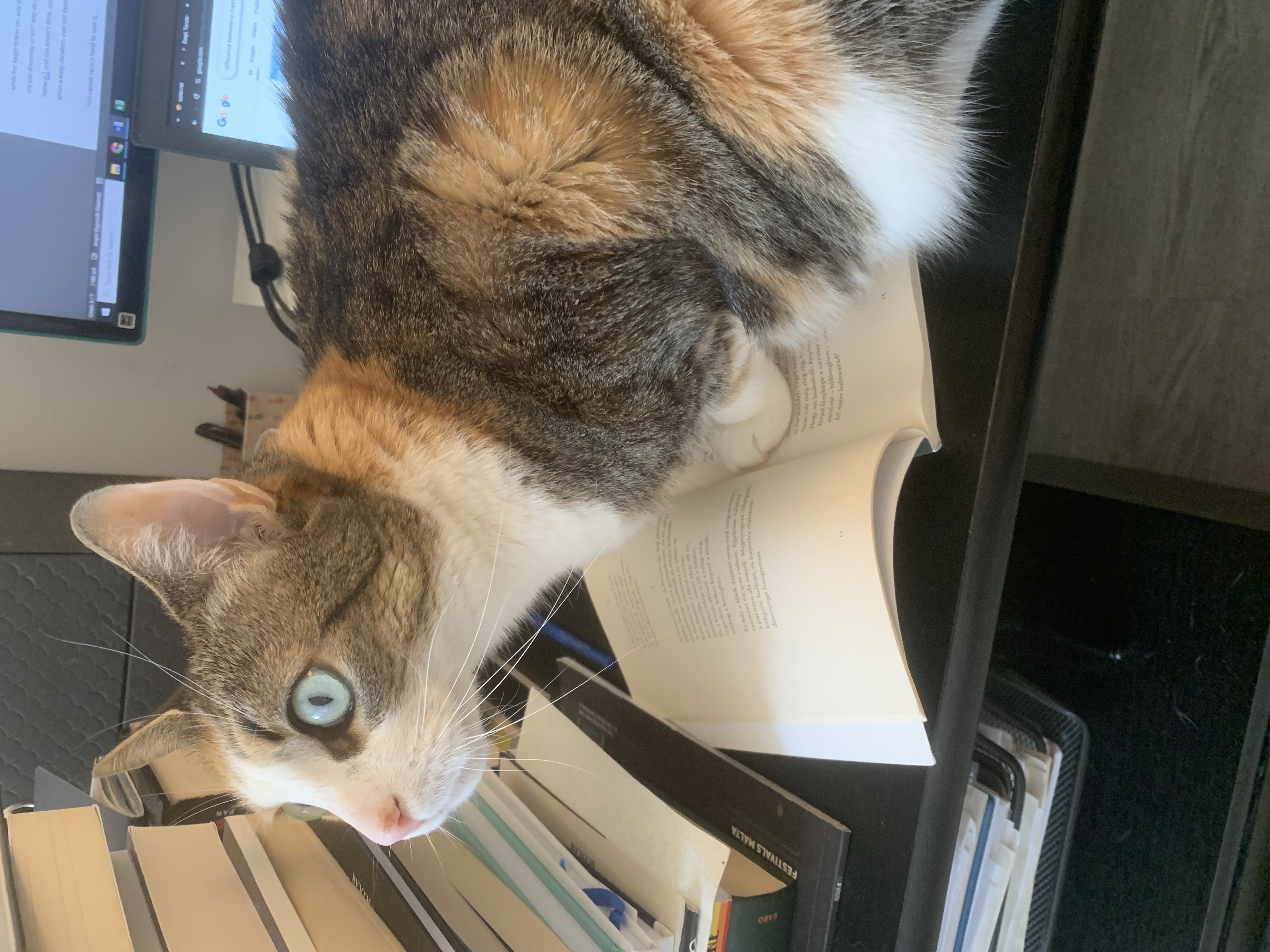

Austin: Aretha helping me translate poetry.

MVU: That is such a beautiful description of the magic of writing, from both angles! What else might an average reader not know about the process and art of translating stories or having your work translated? Can you share more about any of the challenges or how the decision-making works, or something that has surprised you?

AM: Hungarian is a very small language. Damned difficult too, but beautiful, and a joy to play with. We have many exceptional translators working into other languages, but few who understand speculative fiction. Austin moves about comfortably in both literary fiction and fantasy alike. Translation requires trust. It’s a similar relationship to the one between writer and editor, there’s a lot of back-and-forth about what exactly this or that bit means, how many layers of meaning there are, what nuances we need to be aware of. The text is broken down into parts and rebuilt in a different language.

One of my novels, Anchorage (Horgonyhely), was recently published in Czech in Veronika Erdélyi’s outstanding translation. I don’t speak a word of Czech, and it was a particularly strange feeling seeing that text; it required even more trust. I can read in English, get a sense of a text’s rhythm, feel that it’s my own. But the fact that others get to see the strange stories floating around in my head without any language barrier is still the best feeling. Translation is a bridge, and the reason I write is to create bridges with the people I will only ever meet through the text.

AW: If there’s anything close to a maxim I have for translating, it would have to be this: how would the author have written this if they’d written it in English. Which is very different from how non-translators probably assume it works, which might be more like how do I turn these Hungarian words into English ones? I think less about the specific words on the page, and more about what I know of the author and their work, how they write, how they think, the atmosphere they’ve created, what sorts of English words would make their eyes light up. This might ruffle some other translators’ feathers, as it sometimes takes me further away from faithfulness to the original text, and closer to something that is X% translation and Y% adaptation, but I firmly believe all translation is, to some extent, a new, adapted text. I always pepper my translations with notes and questions for the author, things like: “what if we add/cut a sentence for this/that reason,” or “this wasn’t in the original, but it works so well and so perfectly fits your voice, what do you think?” But I never stray so far as to change key plot points or add huge chunks of text, and I never make any bigger changes without the author’s consent, so don’t worry, you’re still getting the “real” story, just one that’s optimized for English.

MVU: As an editor I relate so much to that approach of trying to tap into what I know of the author and their unique style and mindset. I can see many parallels there. Austin, I saw that you translated an excerpt of Anita’s novel Irha és bőr (Skin and Hide) for Hungarian Literature Online. Was this how you two first met? Can you tell us a little about your editorial work at HLO?

AW: The first project Anita and I worked on together was a series of essays, short stories, and novel excerpts for Panodyssey, a sort of literary social media platform that partnered with a handful of Hungarian writers back in 2023, and I think that Skin and Hide excerpt stemmed from that project. Since then, we’ve regularly stayed in touch about potential projects, journals or publishers we could submit to, etc.

I’ve been an editor at HLO for nearly four years now. We’re an English-language literary hub that covers all things Hungarian literature, from new releases and excerpts to interviews and portraits of writers. We’re a small operation, but I’m really proud of the work we put out on a consistent basis. While we don’t usually deal much with spec fic, the other editors occasionally cave in to my pleading and give me a month or so to focus on sci-fi, folk horror, weird or bizarro, stuff like that. So there’s plenty of material there to interest Apex readers: another interview with Anita, the excerpt from Skin and Hide you mentioned, even a fascinating essay that applies philosophical and linguistic theories as an interpretative framework to “Liecraft.” Beyond Anita’s work, we also have an excerpt from and review of László Sepsi’s Fruiting Bodies, a truly outstanding work of Hungarian spec fic (gothic noir mushrooms, it’s a real treat), a short story and excerpt from Hungarian horror icon Attila Veres, an interview series with writers who have scientific backgrounds (Anita included), some truly bizarro work from Zoltán Komor, Csenge Fehér, and art theorist Mario Z. Nemes, and even some absolutely mad poetry from computer programmer Ákos Balaskó. So, dear reader, once you’ve finished this interview, head over to HLO to continue exploring Hungarian spec fic!

MVU: Amazing, what a fantastic menu of reading to explore! Anita, in an interview with Austin for HLO, you said this lovely line I wanted to quote: “I don’t think there’s anybody ill-suited to reading, they just need to find the books that speak to them.” Could you tell us about the books that, above all others, speak to you (whether from childhood or more recently)?

AM: As a child I didn’t like reading. Not one bit, despite how much my parents tried to encourage me. I was interested in storytelling, I was constantly dreaming, coming up with stories in my head, but it was video games and movies that I took to. In hindsight, it was probably because of my ADHD. I had a hard time concentrating on the written word, but my imagination was churning incessantly. Then when I was twelve, The Lord of the Rings and Stephen King’s The Shining fell into my hands (one of my friends stole them from her older brother’s bookshelf), and I suddenly realized: these were the books for me. I became a ravenous bookworm, all I’d needed were the right books. Atwood, Jemisin, Susanna Clarke, and Lev Grossman are some other favorites. As for writers working outside of English, I love Karin Tidbeck, Hannu Rajaniemi, Marina and Sergey Dyachenko, or the Icelandic writer Andri Snær Magnason. I’ve been reading Mariana Enriquez lately, a string of her books has been getting published in Hungary, and I can’t put them down.

I love the strange and surprising, experimenting with the tools of speculative fiction and the search for new paths excites me. I love clever worldbuilding, but the human side, the personality, the empathy and humanism of the text is just as important. I like when speculative fiction holds a mirror up to reality and helps us understand it better.

MVU: What about you, Austin? I saw that you are a huge fan of speculative fiction. What are some of the works that you feel have shaped you, or that inspire you today?

AW: It’s funny, my story is in some ways the polar opposite of Anita’s. I adored reading from a young age, could sit and read for hours on end, but only recently did I turn that love of reading into a career in translation. That being said, Tolkien and King were hugely formative writers for me, so in that regard maybe our stories aren’t so different. Later I fell hard for horror, probably because of that stack of Goosebumps book I had growing up, so figures like Clive Barker, Lovecraft, classics like Dracula and Frankenstein, became staples. As for books I haven’t been able to get out of my head since I read them however many years ago, Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves comes to mind as one of the most innovative, jarring, disturbing, haunting reads I’ve ever come across. I reread Han Kang’s The Vegetarian at least once a year. As for more recent reads, Rebecca Kuang’s Babel, Octavia E. Butler’s Kindred, and N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became were some recent favorites that should honestly be required reading, and Babel may be the read of the decade so far. I’ve also started Ken Liu’s The Dandelion Dynasty series, as well as Cixin Liu’s The Three-Body Problem trilogy and am loving both. Like Anita, I want my spec fic to say something, to explore some broken aspect of our society through a fantastic lens, to make us want to heal that brokenness—really, that’s what great spec fic is.

MVU: Our tastes in reading are very much aligned, but you have both dropped some titles here that I will now need to hunt down. I like to end our interviews by asking for a charity you care deeply about and would love to boost. Could you each share a favorite charity of yours, and let readers know a little about it?

AM: I’m so glad you asked this question, because it’s an especially important topic in Hungary right now. The government is making it very difficult for civil rights organizations to function. Just a few months ago, for instance, they tried to ban Pride, but thanks to many people’s collaboration and advocacy, we ended up having the biggest Pride ever. I’m sad to say the government is also clamping down on literature: children’s and YA books depicting LGBTQ characters now have to sold in plastic wrap to prevent them being opened in stores, and they aren’t allowed to be sold within a certain distance of schools. So the stakes are high. We want to live in a country where everyone is equal, and we can no longer just sit quietly on the sidelines. There’s a saying that Hungarians are prone to passivity, to simply enduring things, but this isn’t true. There is solidarity within us, cooperation, compassion, a willingness to help. When the government builds a fence on the borders with Croatia and Serbia to keep refugees out, civilians give them food and lodging in their own homes. We always have a choice. So instead of highlighting one specific issue—our home is burning in multiple places right now, whether it’s environment protections, LGBTQ rights, the rights of women and children, etc.—I would emphasize the importance of action. Passivity is the worst possible thing we can do.

AW: I couldn’t agree more with Anita’s sentiment. Hungary is and has been experiencing an extended crisis of attacks on civil liberties, NGOs are being killed by a thousand cuts, rights are being cracked down on if not outright trampled over. Institutions of education, art, and literature are either being taken over by the government or their organizations are being stripped of funding. But like Hungarians defiantly showed with Pride this year, they aren’t just rolling over, and here and there shine glimmers of hope. For Hungarians, action is key; for non-Hungarians elsewhere in the world, pay attention, and don’t let your leaders drag you down the slow descent into fascism.

But because I’m a teacher’s pet and can’t not answer a question as it was asked, a specific group I’d love to call out is MFÖEK (Mindenki fogadjon örökbe egy kiskutyát, loosely translated as Everyone Should Adopt a Little Pup). My wife and I adopted our dog from this organization, as did Anita and her husband, so I know there’s a warm fuzzy place in our hearts for this group—they work with local shelters to get animals into loving homes. It may seem like a small thing in comparison to the massive challenges Hungary faces right now, but I’m an animal lover who firmly believes that how we treat our four- or otherwise-legged friends says a lot about how we approach our fellow humans with empathy.

Anita: My partners in crime: Pöpsi, Bumbi & Borsó.

Austin: Stanley and Aretha.

MVU: I absolutely agree on all counts. Thank you for sharing your story of what’s happening in Hungary and for those inspiring and important words, as well as for your wonderful insights about writing and translation. Before we sign off, do either of you have any exciting projects coming up that readers should look out for, or is there a new release by someone else that you’re especially excited about?

AM: I’m working on a new novel in Hungarian at the moment. It has to do with the body, and how politics makes use of our memory. It still needs a lot of work, but I’ve really taken to it. Every novel is a new challenge, and I try not to pull out my previously tried-and-true solutions, but rather turn toward new worlds, forms, and narrative tools. This is how I keep up my enthusiasm, writing as passionately today as when I first started. Writing’s greatest reward is the joy you feel while writing.

Austin and I also have another project we’re working on, a translation of one of my novellas. It’s called Freedom of Contract, and takes place in a fictional Eastern European country where the laws of nature can be modified with legal contracts, and this leads to social inequalities. I would love for it to be available in English someday. It’s difficult to break into bigger markets from such a small language because authors often have to finance the translations themselves, and only afterward can they send the text out to journals or publishers. There are so many incredible Hungarian writers, and it’s only the language barrier that’s stopping their work from reaching a wider audience. We have the occasional positive example though, like Attila Veres’ collection of horror short stories, The Black Maybe, which was shortlisted for the Bram Stoker Award in 2023. And now I too am grateful to Apex for seeing something in “Liecraft” and introducing it to English-speaking readers. As a writer working in Hungarian, it really is an incredible feeling.

AW: As a matter of fact, I need to wrap up answering these questions and get back to editing my first translation draft of Freedom of Contract … Other than that, we have another excerpt from Anita’s novel Skin and Hide that will be published by spec fic magazine khōréō later this year, so if you liked “Liecraft” or read the other Skin and Hide excerpt on HLO, keep an eye out for that one!

Outside of the spec fic world, I’ve been working on a lot of poetry translations this year. I’ll soon be finishing the first volume from Hungarian poet Júlia Kustos, one of the most innovative and exciting young poets in the Hungarian scene today. So if by some colossal turn of fate someone reading this is the managing editor for poetry at a massive publishing company, hit me up. Translating poetry scratches a very different itch than translating prose; it’s somehow both freer and more restrictive, it demands a creativity born of limitation. It’s almost puzzle-like, but a puzzle you get better at solving the more rap you listen to. But ultimately, whether it’s poetry or prose or screenplays or children’s books, translating is an absolute joy, and seeing the fruits of that labor of love find a home in publications like Apex is an incredible honor.