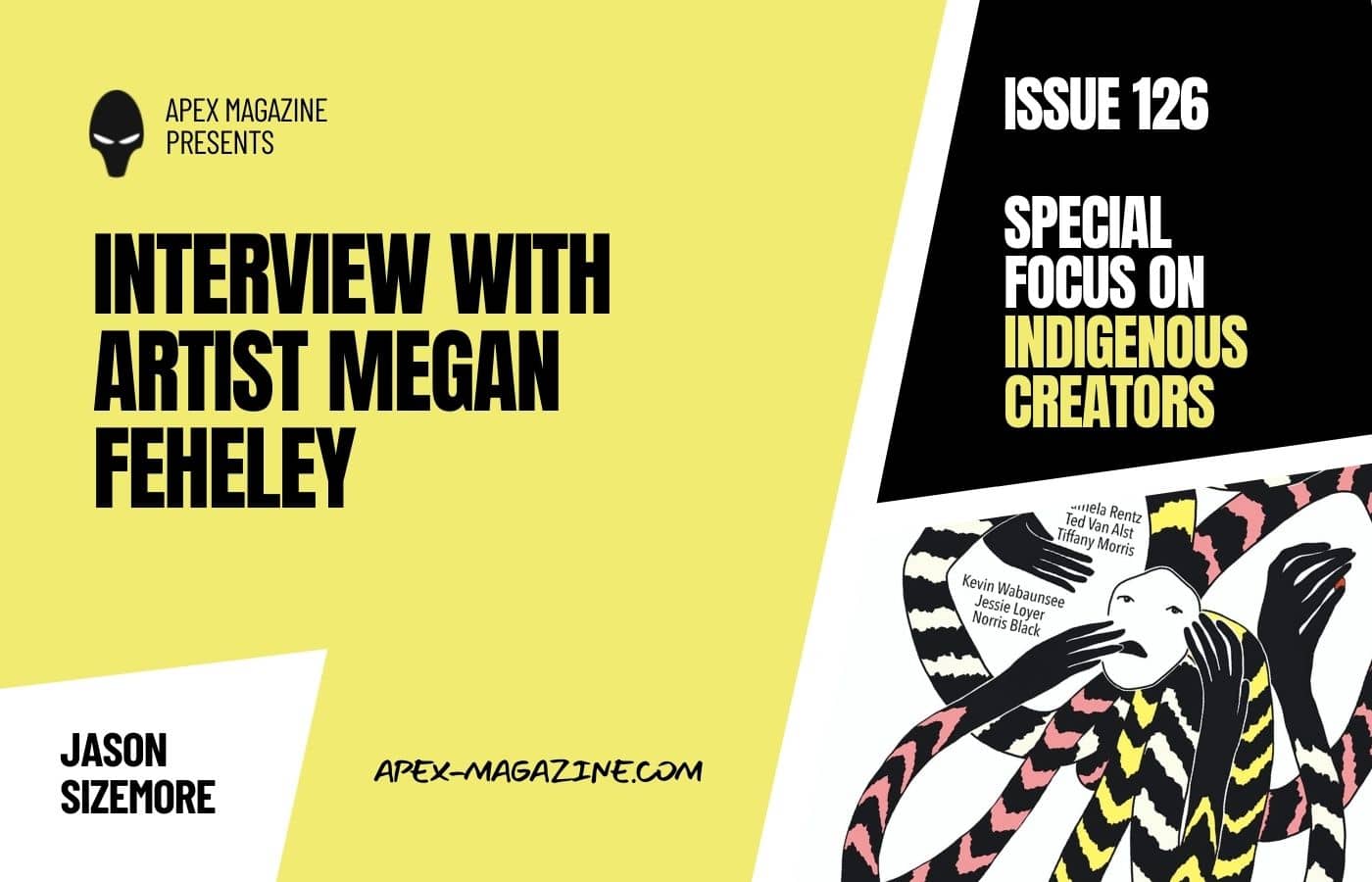

An issue ofApex Magazinefeaturing Indigenous creators would be incomplete without gorgeous cover art by an Indigenous artist. Our issue’s guest editor, Allison Mills, handpicked interdisciplinary artist and curator, Megan Feheley, to create an original work for us.

Megan lives and works in Toronto, Ontario, and is studying toward a BFA in Indigenous Visual Culture at OCAD University. While predominately using the mediums of sculpture/installation, beadwork, textiles, painting, and video, Megan makes their art in collaboration with community and land, with specific interests in environmental justice and decolonial approaches to art-making. Their current focus includes upcoming curatorial projects as well as ongoing experimental installation work.

You can find Megan’s website atmeganfeheley.format.comwhere you can view samples of their beautiful work. They also maintain an active Instagram presence@sakihitisowin.

§

APEX MAGAZINE:Unlike a lot of the artists we feature in our zine, you often work with physical objects instead using a digital space. I’m really impressed with your beadwork.These piecesare straight up amazing. When creating beadwork, how does it compare to creating a new piece of painted art? I’m thinking in terms of physical demands, mental preparation, and how you approach the project.

MEGAN FEHELEY:Thank you! Beadwork is artwork and cultural expression, it’s also a very community driven art practice; I learned beading by sitting in on beading circles, and still bead with friends. It’s a very grounding thing, and the materiality of it is so interesting to me. Beadwork is wearable, durable, and endows a little spirit or being into what you’re creating.

Beading is sort of like drawing with pixels—but the process is very different than a drawing or a painting. I usually prepare a piece by drawing patterns that I know will work well as beadwork and combine colours from my bead collection that I think would be fresh and interesting. Sometimes I design beadwork patterns that reference beadwork from my territory, although I do experiment quite a bit. It can be a bit hard on the hands and neck and involves a lot of intricate work and constant revision; but it is very satisfying and nothing feels better than giving it to friends or family so it can be worn and loved. I’ve also worked with beadwork in a digital space. I worked on a project a few years ago (Uncover/Recover)where I used 3D modelling software to recreate beadwork patterns from a 170-year-old beaded hood from my territory that was in a museum collection. The 3D modelling remixed the beadwork from the hood into a digital space where it could be accessed by our community again.

AM:On your website’s ABOUT page, you hint at an “ongoing experimental installation work.” This piqued my interest because I like art that’s a bit unusual and difficult to put into metaphorical boxes. Can you give us a hint into what you have in the works?

MF:I have been working on a series of new works that have been pushing the bounds of my typical practice, and they involve a lot of research and ephemera. As an example, I installed a work last fall at Xpace Cultural Centre in Toronto calledmâsikîskâpoy(a time-based work involving cedar boughs, blocks of ice, and tobacco) that was the basis of some new ideas for me, although it will take some time before they’re brought full circle.

AM: Something you do is create these vivid red tarps bearing intricate patterns and text in ililimowin (your dialect of Cree). Can you tell us a little bit about these works?

MF:Yes—I tend to call this body of work mybirch bark tarps.It is a very material-driven body of work rooted in my entangled concerns with climate disaster and Indigenous cultural knowledge loss/erasure. The patterns are based on birch bark biting designs, an Indigenous mark-making practice that involves using thin sheets of birch bark, folded several times and bitten to make designs that are revealed once the bark is unfolded. I take the patterns from birch bark bitings I’ve created and transfer them onto the tarps by folding the tarps like I would the bark and cutting the patterns with an X-Acto knife.

Birch bark is such a central and important material for many Indigenous people and is used in a many peoples’ art and cultural practices. Creating the birch bark biting designs in the plastic tarp material transforms it as a mode of transferring knowledge visually in a world without birch bark, a growing anxiety and possibility with impending climate catastrophe.The permanence of plastic in this work is something considered to stand in duality: it is a product of an extractivist industry that has been weaponized against Indigenous bodies and land and is inescapable in this day and age; but is also something that is utilitarian, recyclable, inexpensive and could survive impending climate events where birch bark may be scarce, entirely extinct, or in other ways unavailable.

My understanding of ililiw/Cree visual culture is that objects and belongings have a certain lifespan and weren’t intended to last forever: it is a vital function for things to be remade and retold so that the teachings they hold can be recontextualized for another generation. Colonization has violently interrupted this mode of production through apocalyptic events that Indigenous peoples have (and haven’t) survived, and my concern is about any future events caused by climate change that could jeopardize our knowledge production and transmission further. Although in a double bind,these tarp piecesconsider how to create things that could potentially withstand generational gaps in production—their permanence is evidence of this anxiety. I also incorporate Cree text into these pieces as a way to speak in a myriad of ways- sometimes to the future, sometimes to the now. I am currently learning ililimowin, which will likely be a lifelong process, and reflect often how fragile this dialect of Cree is. Saying anything in ililimowin to the future feels powerful.

AM:Your piece for our special issue, “Tangle,” displays several characteristics common to some of your work. There’s a sense of interconnectedness, of danger, and a face that looks off in the distance as if in despair. It’s certainly unusual, but we love unusualat Apex Magazine, so it fits perfectly. How would you describe your approach to creating an original piece for a digital short fiction zine since it looks like this might be one of your first times creating for this particular medium?

MF:I don’t typically work in this arena, however ideas of futurity are a frequent topic of conversation in the art world right now and very relevant to my art practice. When Allison asked me about artwork for an issue on Indigenous futurists, I knew what I wanted to create. Something that I think about and try to incorporate into my work is that time from a Cree perspective isn’t linear—it’s fluid, cyclical, and runs into and over itself. I had a sketch of these tangled arms reaching out and into each other that I kept returning to and created an illustration of a character that drew on my thoughts on time. The illustration is of a spirit who was travelling through time and got caught up in between and tangled up in herself, the larger story there is up for interpretation.

AM:Your work communicates a lot of unease and discontent with the evolving ecological disaster our world is facing. Much of the fiction we publish inApex Magazineshares the same feelings of unease and discontent. Do you have any particular favorite eco-fiction or eco-focused work that our readers might enjoy?

MF:I think an important distinction or note to make is the tie between the climate disaster we are currently facing and colonialism—they are one and the same to me and co-produce each other. Indigenous communities have already seen ecological disasters that colonialism has brought and current or impending climate disaster is an extension of that. I think that is partly the source of a feeling of unease or discontent in my work, that and a generational anxiety from being a young person who has been aware of climate change since early childhood and is currently staring down a bleak future. With that in mind, my recommendations aren’t necessarily eco-focused, but the land is present in other ways:

- Moon of the Crusted Snowby Waubgeshig Rice

- Marrow Thievesby Cherie Dimaline

- Parable of the Sowerby Octavia Butler

- Split Toothby Tanya Tagaq

AM:Who are some of your favorite artists? Whose work has inspired you the most?

MF:I have so many! I could list artists who I love all day, but some of my all-time favourites are: Jeneen Frei Njootli, Rebecca Belmore, Maria Hupfield, Caroline Monnet, Duane Linklater, Nadia Myre, Dayna Danger, Joi Arcand and Thirza Cuthand. I think I find it tricky to say someone has inspired me the most, but I will never forget the first time I encountered Jeneen Frei Njootli’s work early in my undergrad. It changed how I thought about my art in a fundamental way, and broadened how I thought about art in general. I am also very inspired by my peers in the art world, my community and my family—my mom is also an artist and taught me how to draw and paint. She is still helping me make work, and is my most valued critic.