In 2015, Troy Wiggins’ story, “A Score of Roses” appeared in the anthology Long Hidden: Speculative Fiction from the Margins of History. His story utilized AAVE (African American Vernacular English). This use of AAVE was called a “literary trick” by a reviewer, and that started a controversy.

Here’s the thing: AAVE should be accepted, and this sort of thing, ideally, SHOULDN’T have happened.

But it did. And it does.

So.

Not enough genre peeps are being published writing in, for lack of a better word, non-Eurocentric dialects/vernacular. Notice I specified non-Eurocentric. I’m going to focus mostly on Patois in the Caribbean. Because, as Shakirah Bourne says in her GetWrite article “On Dialect – How Caribbean people supposed tuh talk in a story, eh?” in regards to Irvine Welsh and his very famous Scottish novel, Trainspotting, saying:

…how the ramgeorge people can love, read and accept the language in this book, and then complain and cry down bout lil Caribbean dialect in novels, saying nuhbody won’t be able to understand it?

She mentions different reasons why this was so, but the reason I suspect is “Maybe he was a confident, white male and so no one thought to question him.”

That’s disheartening.

Modern science fiction in the North America is missing out because some readers act as though writers who imagine entire worlds can’t manage Patois, but since the Windrush Era, Caribbean authors have been publishing in the UK to great acclaim, in both full Patois and partial/code-switching. One of the best examples of this is Samuel Selvon’s Ways of Sunlight, which includes a story “Brackley and the Bed” written in full Trinidadian Patois. The opening of the book also contains an intro where Selvon explains his choice and usage of Patois. “Brackley and the Bed” is hilarious and represents exactly the way Trinidadians talk, only with standardized English spelling:

Brackley hail from Tobago, which part they have it to say Robinson Crusoe used to hang out with Man Friday. Things was brown in that island and he make for England and manage to get a work and was just settling down when bam! he get a letter from his aunt saying that Teena want to come to England too.

Caribbean literature has a rich, award-winning history of works filled with Patois, and US/Canadian speculative fiction readers are missing out on what contemporary literature has known for a century.

Other Caribbean writers who wrote critically-acclaimed works in Patois are Earl Lovelace, Derek Walcott (mostly poetry), George Lamming, and Edgar Mittleholzer—the first best-selling author from the Caribbean in Europe who built an audience on Gothic novels. “My Bones And My Flute” is an early example of speculative fiction done in Patois, specifically horror. Neil and Undine Guisseppi have also published many books and stories that go back and forth between the Queen’s English and Caribbean dialect.

Patois and identity/region

This is something that’s addressed in Joanne C. Hillhouse’s Wadadli Pen blog article, “Reading the World: the Caribbean Leg.” She says:

One telling thing in Ann’s responses is that she found no formula to Caribbean fiction. Thematically, stylistically, tonally, they were as diverse as the countries and writers, themselves, as diverse as we who live here know we are.

“There is certainly no lack of stories to tell,” Ann said, “and publishers looking for fresh voices will find plenty of them in the region.”

Case in point: I grew up in Trinidad. Celeste Rita Baker’s from the Virgin Islands. Even I had to ask Celeste what certain local Patois expressions she used meant when editing her short story, “Name Calling,” for Abyss & Apex.

Another example, this one personal. When I came to Canada, it took me YEARS to break through the Patois barrier and understand what a Jamaican was saying. To this day, still, if the accent is thick enough, it’s impenetrable to me.

Also, from the introduction, Samuel Selvon’s Ways Of Sunlight:

When Selvon started to write in the 1950’s it was almost universally believed that the language which most of the people in the West Indies actually spoke (rather than what they were taught in school) was merely a dialect of Standard English. However, in recent years there has been an increased awareness that what were thought to be merely inferior types of English are in fact varieties or dialects of a language - West Indian Creole -which exists in its own right with a structure and vocabulary of its own. And although West Indian Creolecertainly has some affinities with Standard English it also has affinities with West African languages, with Portuguese, with Dutch, French, Spanish, and all the various other influences which have contributed to its development over the years.

Jamaican is now officially its own language, like Kreyol is in Haiti.

Here’s an illustration of Trinidadian Patois use:

Regional accents are common within the United States. If a character from Brooklyn says there were “toity-tree poipple boids, sitting on a coib, choiping” or a Bostonian says, “Pahk the cah in Havad Yard,” nobody blinks an eye. Why should they not extend Caribbean dialects the same courtesy?

Let’s apply that to writing. What are the sincere supposed to do to understand Patois when it varies sharply from island to island, when even people from various islands have to translate their local Patois to each other?

Simple. Make it consistent throughout the piece. I agree wholeheartedly with Shakirah Bourne and her suggestions for depicting something as fluid and widely varied as Caribbean (English) Patois:

Be consistent – If you decide to use ‘tuh’ for to, or ‘wunna’ for you all, keep doing it throughout the story.

That’s basically ALL we at Abyss & Apex did with Celeste Rita Baker’s piece that we published in 2015, “Name Calling.” Really. You can check it out for yourself; we posted both versions for those inclined to make a ruckus about the “editing” done at the time.

In the end, though, I wasn’t countenancing ANY criticism of the treatment of the Caribbean Patois in “Name Calling” if readers weren’t from the region. If Nalo Hopkinson (Jamaican-Canadian) was publicly cheering me on, I felt I had nothing to worry about. In any event, there wasn’t any criticism from any writers from the region.

The other problem (Hurdle? Challenge?) when stories with Patois/dialect/vernacular are published (or even earlier in the stage, edited), is, it is often misunderstood.

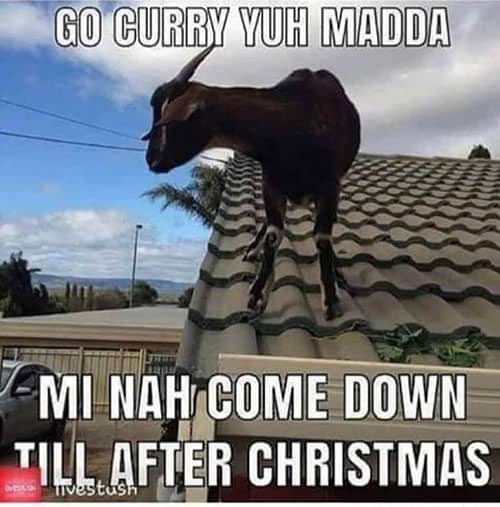

Even for something as simple as posting a meme on Twitter, that my godmother (who hails from Jamaica) messaged me on Facebook, I decided to translate it for those who weren’t up with Caribbean vernacular who read my timeline. Here it is:

Translation:

“Yuh madda” = “your mother/yo mama”

“Mih nah come down” = “I ain’t coming down”

Another case in point? Troy Wiggins’ case, as mentioned at the start of this article. I have run into that myself: I have had people say that the Patois was hard to parse and inconsistent in story edits; I had to mention that not only was that called code-switching, that I have had my fiction used in workshops as examples of GOOD code-switching usage. This seemed to convince them, and I had no problems after that. (Mind you, I got along quite fine with these editors at the time, so it could have been a misunderstanding that was quickly remedied at their end.)

The possible pitfalls of writing completely in Patois/dialect/vernacular? Well, there’s the chance that people may not understand what you’re saying. But, then again, as Shakirah Bourne further points out in her article, from a review: “American readers can use the glossary in the back to translate the slang and dialect—essential, since the dialogue makes the book.” We can adjust to anything because humans love patterns.

If you want to write in Patois, or in dialect/vernacular, more power to you.

Some may want to switch between Standard English and Patois/dialect, as RSA Garcia did in “Douen Mother.”

I mean, as Shakirah Bourne rightly pointed out: “If a Caribbean author doesn’t write Caribbean dialect, who else will?” Caribbean people already become upset or annoyed, in movies, at the accent of the token black person from the Caribbean (normally representing Jamaica), complaining about how fake it sounds.

Assuming you want to write in dialect …

Here’s another article: “Do or Dialect: 6 Tips for Building a Believable Voice." Taking a look at this article, I’d say the first, “Don’t write out the dialects phonetically” and second, “If you must write out dialects, use a light touch” are the products coming from a dominant Eurocentric culture, and that it’s a product of its time, even though it’s 8 years ago; seeing as I’ve published the first ever fantasy story written in complete Patois in a North American speculative fiction magazine, and it’s been received quite well, I think using a light touch is moot. I heartily recommend 3-5, however, “Rely on syntax and grammar”, “Use colloquial expressions”, “Pay attention to rhythm”, and can take or leave number 6, “Describe the qualities of the voice separately”.

In the argument for writing in dialect, I would point out A Clockwork Orange. In case you didn’t know, or have read it, the dialect is entirely made up.

‘What’s it going to be then, eh?’

There was me, that I Alex, and my three droogs, that is Pete, Georgie and Dim, Dim being really dim, and we sat in the Korova Milkbar making up our rassodocks what to do with the evening, a flip dark chill winter bastard though dry.

That’s how the book begins. No one flinched. Instead they taught it to teenagers who then learned Elvish, High Valerian, and Klingon. On Duolingo, if necessary. In other words, the audience is there. Give them the work.

And you know what, folks? Everyone code switches. We use slang with our friends and then perfect grammar with authorities no matter our culture and skin color, so the arbitrary resistance to unfamiliar Patois/dialects is ridiculous.

Some Suggested Solutions

To the issue of not enough genre peeps being published writing in (for lack of a better word) non-Eurocentric dialects/vernacular; have diverse editors on staff so writers feel more comfortable submitting.

And as for dialect/vernacular pieces not being understood: we need more reviewers with these backgrounds doing the reviewing. You’re not going to ask someone who’s a basketball coach to review a ballet; you’d ask someone who is an expert on ballet.

The black diaspora and mainland black African culture, like all others, is wide and varied. Not sure at the vastness I’m hinting at? Try finding out the various indigenous languages present in Nigeria alone. While I can only speak with certainty of the Caribbean aspect of the Black diaspora, and then only with absolute certainty of the Trinidadian vernacular that I’ve been exposed to while I lived there, I have mentioned African American Vernacular English in this piece.

A good primer: Dictionary.com’s United States of Diversity series: African American Vernacular English — “What Makes African American Vernacular English Distinct And Complex.”

Also called Black English or Ebonics, a blend of the words ebony and phonics, AAVE is unfairly stigmatized and sometimes labeled ‘bad English.’ But the grammar is actually as complex as Standard American English (SAE), possibly even more so, and with different rules.

Different dialects have different rules. We should embrace diversity, and learn them.