MojitoWaiter Transmission—275—

Dialogue: HELP. CEASING TO BE.

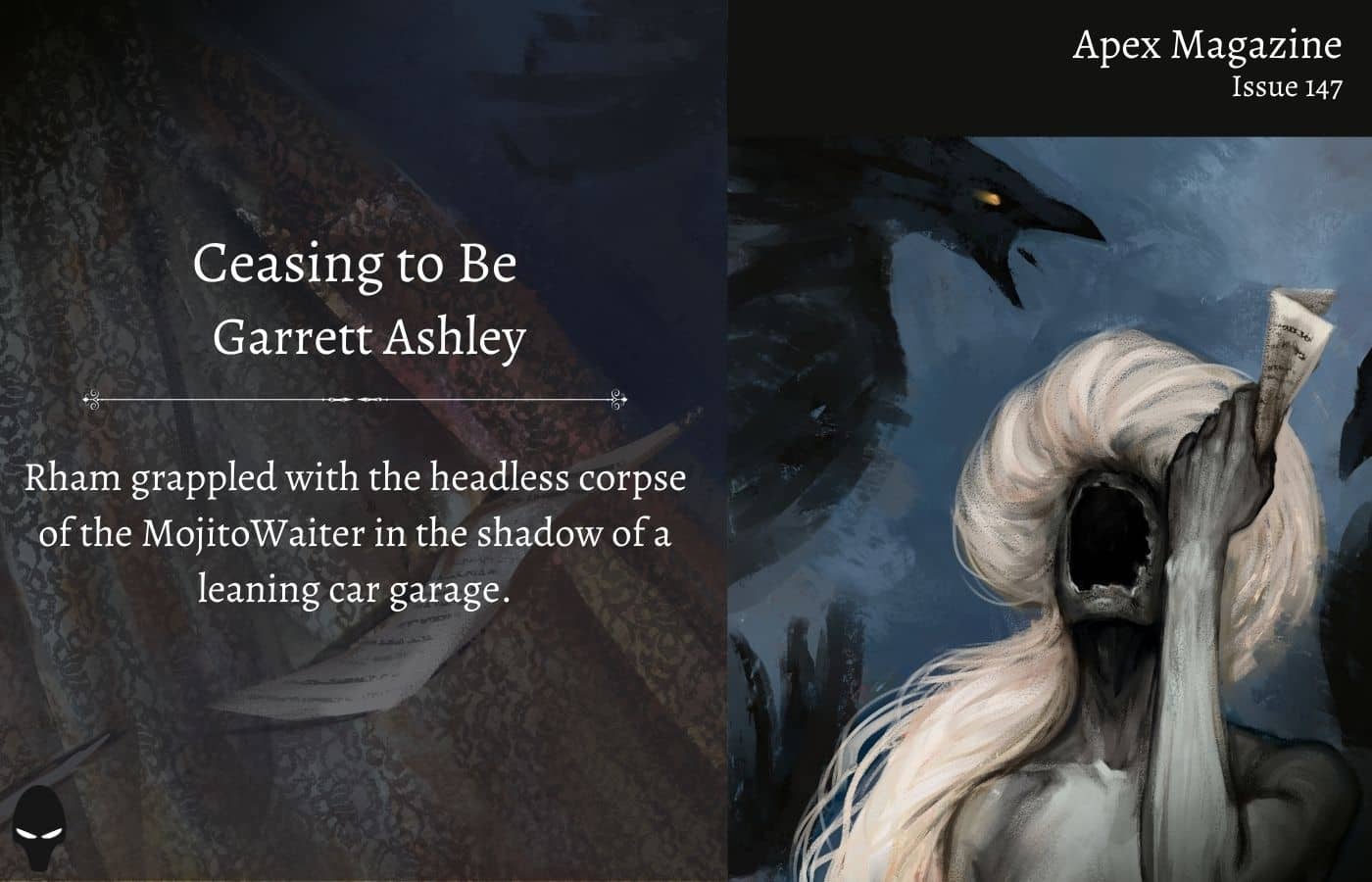

Rham grappled with the headless corpse of the MojitoWaiter in the shadow of a leaning car garage. The artificial had already drawn blood: a flap of skin hung from Rham's face after taking a hit from its aluminum fist. He'd warned me to stay behind him because the body might still be functional. This was the price of getting to the scene of death before other scrappers.

We'd been kicking around in the tall grass looking for its head when the body leapt out and attacked. It went for the more immediate threat; my bulky, wrench-wielding stepfather.

Pivoting at the waist, the MojitoWaiter flung its arms around, the self-preservation kit giving every bit it had left. It walloped Rham on the shoulder, knocking him down, and his wrench flew into the grass.

Rham out of the way now, I blew a hole in its chest with the shotgun. The robot whirred into a slow stillness.

He got up and snatched the shotgun from me and stormed back to the truck, threw it across the driver's seat.

"Anyone could have heard that, Muni."

"You look like you've been in a bar fight," I said. "Whenever you go home looking like you’ve been nearly killed ..."

But Rham wasn't listening. He cleaned the blood off his face, and I got out the metal detector. The MojitoWaiter's preservation kit, upon noticing some problem, the absence of a soul, or whatever was happening to AI lately, had forced it to rip its head from its body and throw it into the bushes.

The metal detector thrummed; I felt it with my boot, saw the face down in the grass. I picked the head up with my free hand like a softball.

I showed it to Rham at the truck. "I think it's supposed to look like Audrey Hepburn," he said.

The muscles underneath the synthetic skin tightened suddenly. I dropped it on the asphalt. Rham smiled, picked up the head. His muscular fingers were dry and cracked. "She won't bite you."

"I think it was trying to talk."

He laughed. When Rham heard about the reason so many of them were offing themselves he told me, without any sense of irony, that it sounded like a theory someone my age would come up with.

But I had no clue what people my age thought about; I didn't spend much time with anyone other than Rham. Nobody knew that I did this with him. He was always telling me that I needed to introduce myself to some people. Just go right up and sit next to them, he'd say.

He copied the serial number from underneath the chin and I bagged the head and put it in the ice chest. We'd disassemble it later, collect the black box, and prep everything for resale.

Three students from junior year had been chosen to fly to classes at Huxley to learn about neurotechnology. I wasn't one of them. I stayed in trouble. Principal Miller kept an eye on me; her drones followed me everywhere between classes, threatened to zap me if I even looked like I might lash out at any of my classmates. In exchange for three of our highest performing students, Huxley sent over three child-looking artificials, their craniums fitted with an updated version of a procedurally-generating AI system that was still in the beta phases. The idea was to study how AI learns and adapts to other humans who are also learning and growing; they'd go to classes with us, sit with us in the lunchroom, and hang out with us at recess. I needed extra credit in my social networking class, so I volunteered to let one of them follow me around.

Miller, happy maybe that I was trying to do better, asked me to sign a waiver. She made me read every sentence of the contract; turns out, I'd be in deep shit if I dropped one of them down a well or got it run over by a car.

"Do not make me regret this," she said, scratching her name across the bottom after I'd signed my own.

Anne, the artificial assigned to me, had skin like rubber with hair punched in like a doll's. Her face, though, was expressive, not as uncanny as a lot of the models you'd find giving company in nursing homes and care facilities. She wore a pair of white medical gloves for a little while then took them off, threw them away. She had a stride that had human qualities but was too consistent to be quite human. A slight whir sounded from her joints.

We didn't talk much at first. Anne held doors open for me. I swatted her hands away during class when she tried to play with my hair. She mimicked what she saw in class—passed me a folded-up piece of paper, one day, the drawing of a three-armed Dracula riding the back of a unicorn.

I turned back to her, the paper still in hand. "Have you ever seen a horse?"

"I don't think so," she said.

I knew I was in trouble when Anne started asking questions: she wanted to know about our assignments, how the food tasted, what my favorite sounds were. She waited, eyes-widened, for my response. I'd never thought about my favorite sound before in my life.

"Have you ever seen childbirth?"

"Nobody here has ever seen a childbirth," I said, exhausted.

She followed me around school asking questions like this, watched me doing homework, and commented on how Miller's drones were always watching me—just me. When she asked about them, I didn't know how to explain that I didn't handle pranks very well, that I was called poor often and tended to lash out at the other kids. Lately everything had been pretty relaxed. Maybe because I had drones following me everywhere.

A week into Anne following me around, I started to worry she was getting bored, so during recess I snuck her to the drainage ditch. We crawled under the fence, her synthetic fingertips gripping the pipework connecting our side of the school to the highway.

I watched the water rushing below across piles of junk. I wanted to tell her that my people were collectors of junk. I needed someone to know how I lived. But I figured anything I said to her would get reported back to Huxley if they weren't already listening, and some of the black boxes we were hocking must have been their intellectual property, after all.

"Why are we here?"

"Because it's dangerous and we're not supposed to be here. It's private."

"We'll miss class. We'll get in trouble."

"I'll get in trouble," I corrected her. "And this is more important than going to class. Privacy is more important than anything."

We watched the water rush over the junk. It came in brown globs, bubbled milky white over heaps of buckets, plastic rods, car tires, unidentifiable purple filaments.

"I've been thinking about my favorite sound—I haven't heard it in a long time. My grandmother used to make it when she walked. She had a cane that split into three parts, and when she walked with it, it made a creaking sound."

"What was your grandmother's name?"

"Faye. I don't want to talk about my grandmother, if you don't mind."

She looked down at the junk, eyes darting back and forth across the shifting colors.

"What's your favorite flavor?"

"Nobody has a favorite flavor." I realized I was being rude. "You talk. I don't feel like talking."

I thought about my grandmother and her cane. Anne talked about herself, how she discovered that she was female-identifying before coming here. She'd had the option to choose hands with longer fingers or stubby, cartoonish ones. She had viewed over three-hundred hours of sitcoms from the 90s and early 2000s in real time. And since we'd met, she'd already discovered that my stepfather was on a sort of watch list for black market resellers.

"What does he sell? Can you tell me?"

"Do you get police reports up there or something?" I touched her head. "Are you going to report any of this back to Huxley?"

"The only thing that can be ethically extracted from me is psychosocial data and anything that occurs during an emergency situation or act of violence. You can also tell me when you don't want me personally to remember something."

"That wasn't in the contract."

Her eye twitched. "You read the contract?"

"Don't act so suspicious about it," I said.

The contract also hadn't said anything about what to do if or when these artificials went apeshit and killed themselves, either, whether I'd be held liable for something, say, if she were to throw her head into this creek right now. We watched the cars through the leaves, through the smells from the ditch.

I scrambled some eggs and watched a movie called Sabrina, courtesy of Rham's wife. I'd asked Harper if she had anything with Audrey Hepburn. I had my own place next to them within earshot of the river, a trailer that'd belonged to my mom's mom. My grandmother helped raise me after my mother died, kept me fed and clothed while Rham flew in and out of bars and mysterious week-long absences. I stayed here by myself—it was private, I could do whatever I wanted, and nobody ever bothered me. Except the freezer full of black boxes were here, and sometimes Rham would have to come in to collect something.

Now, Audrey was sitting in a car in a garage. She was trying to kill herself. She really did look like the head in our freezer.

I wondered about what would happen to Anne. Anything with an IQ above 65 was stopping in its tracks to have some sort of existential crisis. Maybe the result of a bugged software update, foreign hackers, or just general incompetence. Most artificials ripped off their heads and threw them into the bushes to protect the black boxes from scavengers. This is what they were programmed to do in anticipation of a shutdown, and they tended to do it whenever they felt the call from the beyond, their spirits ceasing to be—whatever that meant.

One of the worst things I ever saw was a family of four that had gotten into a car wreck after an artificial driver ripped its own head off and tossed it out the window. Rham listened to a special radio that intercepted the AI's calls for help before police and the ambulance arrived.

I saw the family’s bodies. We hid the head and waited with the corpses of this man and woman and their two mangled children on the side of the road.

We weren't monsters, after all.

The AI at fault for the deaths had suddenly known nothing but to protect the data in its head, a manufacturer protocol, the non-AI/scripted programs running in the background after its real death, whatever it was that would prove useful to corporate advertising algorithms. It killed people trying to protect its data, so much data that it couldn't properly be transmitted wirelessly.

I wasn't really paying attention to the movie, but Audrey ended up being okay. Some man got her out of the car on time. She cried and played dumb, tricked the guy into believing she didn't realize leaving the car on would fill the garage with toxic gas. I rubbed my hands together, felt their warmth, touched my cheeks, watching her—I was totally different than this actress in every way, but that was fine with me, I told myself. We preserve ourselves in ways unknown to us.

The principal pulled me out of first period the next day. Held me tight by the arm and shoved me against the wall when we got outside.

"What the fuck?" she said. "Do you understand that you're not supposed to take the robot outside school bounds?"

"We didn't go outside school bounds."

"You crawled over a fucking sewer pipe and sat on the edge of the highway."

"I didn't know that was outside of school bounds," I said.

"You were sitting twenty feet above a busy road," she said, keeping her voice calm now. "You know what is out of bounds, you know what is not out of bounds. You're under the impression that I'm an idiot. You don't like adults and you've been through a lot. I get that. But you're living in a fantasy where adults are less intelligent than you because you read fucking Catcher in the Rye or something. I'm asking you kindly: please don't cost the school any money. Don't get mud in its hair. Don't fuck up its tennis shoes. Don't teach it racist jokes. I'm begging you to keep our school out of the news."

I didn't know where this was coming from, but her grip on my arm finally lessened, and she walked away. When I returned to the classroom, Anne was sitting there with her legs crossed. She passed me a note: Did she hurt you?

GrinBOT Transmission—276—

Dialogue: HELP. CEASING TO BE.

We drove down to the GrinBOT’s last known coordinates. Rham had already been drinking a while. No scavengers yet—this place looked clean. We looked around first for anyone that could be hiding in the bushes. GrinBOTs were particularly dangerous to recover; if it had been doing a session with someone out here, someone on the verge of hurting themselves, that person, in shock, might still be hanging around, and you never know people, Rham always said.

We waited under a large bridge, pilings as big as warehouses. Flowers grew up in the cracks from the road. People used to live down here in tents, but had to find someplace else to go after the place flooded. The remnants of the camp dotted the muck; a line of trees stood in the distance, and some buildings beyond that.

My grandmother used to tell me every dog she had—big, little, wild, house trained—would go out to the woods when they knew they were about to die. They didn't want to be found.

"Let's check that way," Rham said.

GrinBOT's body was strewn across a bed of yellow weeds. The arms splayed upwards, and the head, if you could call it a head now, still hung from the shoulders by a few strands of wire. Birds circled overhead, the steak-like smell of burning cables probably piquing their interest.

"Looks like buckshot to me," Rham said, fingering around the wounded cranium. He squeezed my shoulder with his big, dried out hand. "Well, let's get what we can."

I picked up the head and tried to cram it back into the shoulders. For a moment there was a twitch, a fan blowing warm air onto my hands.

Rham slung the torso onto his shoulders. The head fell back down and batting against his hips. We made our way back to the truck and he tossed it into the bed.

We'd just buckled in when another truck drove down the hill and blocked our path. Four men got out, each with a gun strapped to their hip. Rham, drunk, let his window down and said hello.

"Step out of the truck, friend."

"I didn't know we were on private property. My hands," Rham said, showing them his hands still oily from the robot. "I don't have any weapons."

"I said get out of the truck."

When Rham got out of the truck the man wrestled him to the mud and the others stamped him with their feet.

"Stay down."

The men looked into the bed of the truck at the robot. Two of them lifted it out and threw it into their own.

The leader came back around to my window and pointed in at me. "You better take your old man home," he said. Then they got back in their truck and drove out of the valley and back up onto the bridge. I didn't realize I was crying until Rham was in the driver's seat again, looking at me like I was crazy.

"You good?" His skin was bloodied, his left eye swollen shut. Blood poured down his mouth, neck, pooled around the collar of his shirt.

"Yeah," I said.

He started the engine and we got the hell out of there.

Anne called. I was watching the end of the Audrey Hepburn movie, going back and forth in my head about whether I thought she was under duress or whether she was manipulating the male lead opposite her. Sabrina was lounging on a ship now, dog in lap. A hat is offered to her as my phone rings. Anne's name showed on the screen.

There was a lot of noise in the background—something banging, heavy things being shuffled around.

"You want to come over?"

I looked at the phone again to make sure it was Anne who’d called me. "To the school you mean?"

"I'm calling from the office. Nobody is here but us and the janitor. Come over and I'll let you in."

My phone showed it was a little after midnight. I got dressed and pulled my bike out of the lawnmower shed. I could hear Rham and Harper in their trailer—Rham had been holed up since the attack, too sore to move, he said, his face a swollen mess now, possibly a couple broken ribs. I doubted he would notice if I left for a little bit.

I petaled out to the school. As I approached the main building, I stopped and looked around for the drones. They were folded up in their cubbyholes like gargoyles, their lights turned off. I could see Anne at the door waiting, waving her hand with a big smile on her face.

"Quiet," she said, opening the door as I walked my bike up to hide it in the bushes. I followed her to the office, through the lobby, and into the security closet.

"What are you doing?"

"The janitor's in the cafeteria. I'm keeping an eye on him."

She showed me her charging station in the principal's office; the other artificials were in their charging stations, heads slumped over peacefully.

We went through all of the principal’s drawers and notebooks. There were exam booklets with the answers highlighted in green. There were mid-semester grade sheets, scholarship applications, a list of students on the honor roll, a list of parents to watch out for at parent/teacher conferences, a sampler of vodka, a jar of salt. I picked out a thick bottle of syrup and extended it to Anne.

"Pour it everywhere," I said.

"I can't. You do it."

"If you see me do it, will you do it?"

"I'm not allowed to do property damage," she said. "I could literally go into sleep mode and I wouldn't be able to erase the footage of you coming in."

So I poured the syrup across the contents of the principal's desk myself. Her papers, her tablet, into the #1 Mom cup with all her fancy pens. I poured syrup across her keyboard, into the fans of her computer.

Outside the principal's office, I poured the syrup into the copy machine. It was a huge, expensive piece of equipment. I was about to pour syrup across the secretary's desk, but I didn't think she deserved it. I crammed the sticky bottle into my back pocket and would throw it away when I got home.

"I can feel the janitor coming in my legs," Anne said. She led me out of the building and promised to take care of the surveillance footage.

"Isn't that property damage? Erasing the footage?"

"I don't think it's property damage. It's programmed to either record or erase."

Maybe she was telling the truth—it was difficult to tell. But she seemed really happy that I'd come. Something about the way her cheeks lifted, the way her eyes glowed.

She'd see me tomorrow, she said. "Don't touch anything between here and the road."

"See you," I called out as I started out on my bike. I still had syrup on my hands.

ZayZay9102 Transmission—277—

Dialogue: CEASING TO BE.

"You go to the door," Rham said.

The house looked fine—nothing had happened. There were azaleas out front. A canopy covering two rows of turnips from the sleet.

"Why do I have to do it?"

He stared mechanically at the house in front of us. "Look at me. What do I look like to you?"

"Like you got beat up," I said.

"I look like a criminal. You're a kid. They'll trust you more. You know what to say."

We had a sort of procedure in place for house calls. We weren't exactly out in the country, but we were far enough from the city and these people likely wore a pistol on their hips at all times, and anyway Rham looked like he'd been hoofing it in the woods, had been unable to wash his face because the pain was too much.

I rang the doorbell. Now that I was close enough to the house, I saw how the blue paint was flecking away from the clapboards. Spiders infested the curved metal handrails around the tiny porch. A woman came to the door. She was red in the face, her eyes bloodshot.

She wore a pistol on her hip—Rham had called this one exactly.

"Who are you? It's early."

"Did something happen here this morning? With your robot?"

"How do you know about the robot?"

"Her broadcast," I said, looking around the place. From here it looked like a dusty house, not a lot of furniture in it. "She put out a broadcast before."

"Before," she said. "Before. Yeah, okay. She was in her room. I heard something strange and went in to check on her, when—"

"Her room?"

It surprised me that she talked about the artificial like a person—had apparently given it a room.

"I can't go in there," she said.

"I can take care of everything if you want. You won't even have to look."

I went back out to the truck and got a bag, looked at Rham sitting in the passenger seat. "It's going to take a moment," I said.

"Need help?"

"I don't know," I said.

His eyes were on the rearview mirror now. There was a cornfield, and on the other side of that there was the highway, and a checkpoint leading into the city; the high-pitched squeal of a train could be heard somewhere moving like a serpent over the fields.

When I got back to the house with a bag large enough to carry the whole robot, the woman stopped me at the door.

"Who is that in the truck?"

"My dad," I said. "He hurt his back. May I come in?"

She let me in. I held the bag behind me. I didn't want her to see what I was about to do. I wondered what she was so upset about, but at the same time I think I understood. I'd been there for my grandmother in similar ways, someone to look at and talk to even though I couldn't understand most of anything she said. She knew enough English to get by, enough to make me feel guilty. "Don't leave me," she had said—one of the last things I heard her say before leaving. The broken English, the hint of a crack in her voice as the physical space between us grew. I'd never been able to forget about it, and I heard her everywhere I went. Don't leave me.

The woman let me go into the bedroom. Toys had been flung onto the floor, clothing, a chest of drawers pulled away from the wall. A girl's body lay on her stomach by the bed, her feet curled under her. Anne's size or smaller. A nursing home companion, maybe. The head had been tossed somewhere into the corner. I folded the heavy body into the satchel and found the head in a pile of dresses by the closet. I tried to move quietly; the woman was waiting for me in the hallway.

"What company does your dad work for?"

"Like I said, your daughter called us on a radio."

"You mean you picked up her distress call on a radio," she said. She looked at the bag, a blank stare on her face.

"I know this is sudden."

Her hand was on the gun. She shook her head, crossed her arms and moved out of the way. I was halfway down the hallway when she offered to help. We lifted the bag together and brought it out to the truck. "I hope your back gets better," she said to Rham. She patted his arm and walked back to the house.

"What was that?" he asked me when we were on the road.

"Something depressing," I said.

Anne pulled me aside during recess in front of everyone. I didn't mind—there was nothing inherently embarrassing about a robot trying to be friends with you—but I didn't have friends, I spent most of my time alone, and I was aware of the fact that the other kids would think an artificial was the only thing capable of liking me.

She wanted to come over and see where I lived.

"We just met."

"I might not have much time, Muni. We're dropping like flies, and I want to see where you live before I'm gone."

"You're not going to die."

"I don't think dying is the right word for it. It's just a feeling I have. Something twitching in my—"

"In what?"

"You just don't want me over because you're ashamed of me."

A train flew by in the ditch below us. The sound blotted out the cries of our classmates. "I'm not ashamed of you, and you're not going to die." The bell would ring in a little bit and we'd have to go back inside and I would have this thing sitting on my chest for the rest of the day. I didn't know why—Anne wasn't even a real person, yet somehow all this shit about my grandmother was coming back, stinging.

"You know Miller isn't going to let me take you outside of school. That's the real problem."

"You know she's warming up to you," Anne said.

Nothing was enough. She'd bother me until I gave in. "You're not going to like where I live. But you can come back with me after class."

She left me alone then. I felt uncomfortable, with the feeling of so many eyes on me.

DeskFamiliar Transmission—278—

CEASING TO BE.

Another run—my mind wasn't in it, and I think Rham could tell. The swelling had begun to come down from his face. He told me to sit tight while he did it, but to keep an eye out on the trees for him just in case. We'd gotten this call right after having dinner; it was getting dark and Harper was taking a shower. Rham shook his head, told me let's get it done with and get back.

CEASING TO BE, they'd all say, as if the line had been rehearsed. I figured it out, at some point: "ceasing" is a quick, easy word to say and hear; no matter the quality of the signal, this is clearly understandable. "Be" is where my own existential crisis comes in; they feel that "being" is the opposite of not functioning, that whatever is happening to them is causing them to no longer exist.

Today in geography class it happened: one of the kids ripped their head off and died. We were learning about prime numbers and Goldbach's conjecture when one of the exchange students—she had black hair, some grays, and wore the same sleeved dress every day—made a gurgling noise.

"You okay, Rosy?"

Mr. Coleman's arm was still up at the smart board, smart pen in hand.

Rosy twitched, rubbed her neck. "I'm I'm I'm."

"Okay then," Coleman said.

He lectured for a moment longer, wrote something else down, pausing between sentences to give us time to take notes.

"I'm, I'm I'm," Rosy said.

"You're what? What's happening?"

Suddenly her arms started to jerk and spin; her sleeves tied up in a knot until they ripped. She leapt up, the desk still attached to her, and rolled around on the floor until she was free.

We made room for her to struggle. We backed against the wall; our things knocked around in the chaos. I was the only one who knew exactly what was going on, what Rosy's incoherent mumbles meant, that somewhere on a specialized radio, Rham was getting her full message to us.

"I'm, I'm, I'm."

Mr. Case stood back in the corner, eyes wide, pen still in hand like he could write on the board at any moment.

Rosy pulled at her head. Something clicked, and her skin began to rip, fluid shot out onto the linoleum floor, and her headless body made an athletic sprint towards the window—head in hand like a grenade—and lobbed the head through the glass with an explosion. Rosy's body turned towards the room's door, walked two steps, and crumbled to the floor.

The head had landed on top of a substitute teacher's car, who is also the person who found it: she reported that she had no idea what she was looking at, it didn't even look like a face anymore.

Later, Rham would tell me that was trauma: "I once knew a woman who saw her husband's shot up body in the ditch outside their trailer. She went inside and made mac and cheese before it hit her what she'd seen."

I didn't know the point in him telling me this.

Anne didn't say anything about what had happened to Rosy. Her face didn't give away any emotions. We went to the edge of the woods during recess. There was a thrum from a nearby power station. A dozen or more homeless people lived out there in the trees beyond the fence. The most I could see of their camp from here was a recliner chair covered it what appeared to be a yellow rug.

"I'm sorry about Rosy."

"Did you take her head?"

"No," I said. "That's not how it works."

"How does it work?"

"We take the black box and sell it to people who sell it to people who can't afford their own software engineers. I don't know much about it. I just help my stepdad out."

"I really want to see," she said. "I think it would be interesting if you showed me."

"You promise you're not a spy or something like that?"

"I’m not," she said, twining her fingers through the chain link fence. "I'm just curious about what happens when we die."

Miller signed the waiver for me to take Anne home with me, even broke open a portable charger for her in case she needed it in the morning. "You seem happier," was all she said. She didn't look at me. The bag the charger came in was sticky with syrup.

We rode the bus home together. Rham was still laid up on the couch, and I hadn't heard from Harper. Anne was about to go straight to their trailer when I grabbed her arm.

"In the back," I said.

She followed me to my trailer, taking big steps in her doll's shoes.

"You live alone?"

"For the most part. Rham lives there. He's my stepdad." I led her up the crooked steps into the trailer. The place smelled like cigarette smoke, which I'd never been able to get out of the place no matter how much paint I covered things up with. Anne sat on the couch; a plume of something yellow shot up from under her butt.

"Why don't you live in the same house as Rham?"

"Because we have a complicated relationship. I used to stay here with my granny."

We watched a few minutes of a French movie I'd checked out at the library. Well, I watched a few minutes: Anne kept getting distracted, looking around my trailer. She got up and went to the back door and looked towards the woods through the dirty glass.

"What's back there?"

"A river."

"I want to see the river."

"It's too dark. Do you want to watch the movie?"

She tried to sit through a bit more of it. A guy on business in a sprawling office building was trying to have a meeting with someone high up that worked in the building, but things kept getting in the way. The building was so big and surreal, he couldn't find his way around. There was something really strange about the architecture of the building, like it'd been designed by AI and not humans.

"Do artificials have goals? Like when you're a kid—I mean, when I was really little, I wanted to be a software designer."

"I could tell you that I have goals, but it wouldn't be sincere," she said.

"Oh."

"I could tell you, for instance, that I want to be an astronaut. I could say it's because I want to be able to put the Earth into perspective. Because that's what most human astronauts say, or have said about their careers. If it's available online, I've absorbed the information and can regurgitate it."

"I can't tell if you're saying you want to be an astronaut or not."

"Maybe not," she said.

"A lot of humans want to do things because other people do them. It's not that unusual to regurgitate."

Anne had gotten up again. She stretched her arms and there was an audible pop from somewhere in her chest. She opened things: drawers and cabinets, peaked in, standing on her toes.

"Where do your friends live?"

"I don't know. I only see them in school. Hey, don't go in there."

"Is this it?"

I got up—held my hands out as if to stop her. She'd already lifted the lid by the time I got to her.

We looked inside together. She reached in and pulled out the MojitoWaiter's head. She made a quivering sound, something inhuman, and closed her eyes.

"I knew this was a bad idea," I said. I took the head from her and threw it back into the freezer. Ice shards flew back out at us.

She moved away from me.

"You told me you knew about this. I thought you already knew all about it. I thought—"

"That could be me in there," she said. "I can feel it swimming around in my head like bugs."

"Where are you going?"

She was hard to keep up with, had already knocked on Rham's door when I got around to the front of their trailer.

Harper answered holding a beer. She looked down at Anne, clearly an android, and scratched the top of her head.

"I need a ride."

Harper disappeared into the trailer. "I am not getting into this," I heard her say. It was always dark in there, gloomy, and reeked of stale beer.

Rham appeared out of the dark, his bruised body covering the entirety of the doorway. "You're the robot. And I guess you're up to something," he said, looking at me.

"I need a ride to the school."

"No shit," Rham said. "It's night. There's no school." He closed his eyes, thought about what he was saying. "Wait, are you having a fight? Why do you want to go to—"

"Her charger's not working," I said. "Just give her a ride. She doesn't want to be stuck here powered down."

"I don't want to die," she said.

Rham went back in for a bit then came out, keys jingling. He smelled like he'd been drinking.

"Please don't do anything stupid," I said.

"Like what?"

Anne got in the truck with him. Then they were gone.

Rham knocked at my door later. Came in, two beers in hand. He gave me one, and I stared at it a moment before he sat down. "She had this—" he used his hands to implicate the shape of a box. "I watched through a window. They have little sleeping pods in the janitor's closet."

"She looked in the freezer."

"And had an existential crisis. I know. She had all kinds of questions. She seemed upset."

"Questions about what?"

He squeezed his eyes shut. "I don't know. Questions about us. Your mom and grandmother, all of that. Your real dad."

"It's a seven-minute drive," I said.

"She asked a lot of questions in a short amount of time. She acts like a real person. And I know you're not stupid. I trust you to handle it."

"I don't think she'll tell anyone." I drank some of the beer he'd brought me. My throat burned. I thought of the school—Anne helping me to break in. She liked doing things that were illegal, things that were beyond the scope of her program's limitations. Maybe Rham and I could get a pass as well.

"Just keep your eyes open," he said. "Don't bring it around again. For the love of God."

"Thanks for not killing her."

He got up, went to the door. The smell of him wafting after, the room suddenly clear. "It looks like a kid," he said. "I don't like that. Goodnight."

JackPot Transmission—279—

CEASING TO BE.

I told Rham I didn't want to do it anymore. I couldn't think about death anymore. There were images of death in my brain now that someone my age shouldn't have to own. He stuck his hands in his pockets, nodded his head.

"I'm headed to the casino. I need to get going as soon as I can." He looked towards the freezer. A hum filled the air. "I'll get rid of those soon. I promise," he said.

My grandmother had died right here—basically on her own, and I'd abandoned her. It's one of those things I wanted to tell Anne, but I didn't know how—the way leaving her had made me feel, the excuse of I'm just a kid bad enough on its own. She had been sick for a very long time and I didn't know how to deal with it anymore. She'd had mood swings. She couldn't make it to the bathroom in time. She looked like a ghost. The worst part was that she still told me I love you in the way she always had. When all I could have wanted was for her to disappear before she died, made herself more distant spiritually, mentally, in order to give me time to prepare. I'd take care of her and when I got to school, the other kids would tell me I smelled funny. I could get over that—I knew the trailer smelled bad around the time she died, and nobody knew what I was going through. Maybe I didn't want to accept that death was something we all had to look forward to—maybe it was something else, I didn't know what.

I caught glimpses of Lucy around school and eventually worked up the nerve to ask her about Anne, but she for the most part acted as if she didn't know what I was talking about. When I did see Anne, she avoided me. She didn't pass me notes in class. She disappeared during recess to use the charging station even though I knew she didn't need charging. I waited by the chain link fence near the woods, hoping she'd come and talk to me. A few days passed and I told myself that I needed to brace myself for the future—she was going to be shipped back to Huxley eventually. I told myself that was fine—it needed to happen, I needed to finally grow up and make some real friends.

Redacted Transmission—284—

MUNI I'M COMING OVER.

I was looking for a movie to watch when someone knocked at the door. I thought it might have been Rham come to offer dinner, but it was Anne. She had dirt in her hair, and her shoes were covered in mud.

"I don't feel good."

"You walked all the way here?"

She looked in, maybe towards the freezer, maybe not. She shook her head. "I want to look at the river."

"It's getting dark," I said.

"It's urgent," she said. I could hear it in her voice, something shaky, odd.

Anne held my hand. "I don't. I don't," she said.

"Do you believe in memories? Do you believe that one day I'm going to look back on my shitty childhood and actually miss any of it?"

"I don't know. I don't," she said.

She was going, clearly. Her grip tightened slightly.

"How do you feel?"

"I feel," she said.

I closed the trailer door and pulled her with me. We walked into the woods. She dragged her shoes through the mud. Her footsteps were stiff, unplanned.

Her hand's grip tightened.

We stood beside the creek. She looked down into the water and the water's reflection rippling against the bank.

"Looks like something invisible moving down there."

"Want to get closer?"

"Don't go. Don't leave me."

"Okay," I said.

Eventually she started shaking and reached up to her head yanked at her hair, but I held her down. She tried to get me off her, but she was too weak; I could feel the metal in her struggling to work, to contort. I used my knees to pin her wrists, anything to keep her from ripping her head off like all the others.

"Hey," she said. "Hey."

Eventually she stopped struggling and I got off her. My knees bled. Her eyes were wide open. I reached down to shut them, and they made a slight mechanical whir as they closed.

A representative from Huxley came to claim Anne's body. They were there in a few hours, during most of which I got zero sleep. Rham, not knowing what the hell was going on, started drinking, pacing around the yard and Anne's body, which I'd dragged all the way back home. Eventually, Rham went inside; I stood there with her until the van arrived. They apologized for the inconvenience. "She came a long way," they said.

"It's not that far," I said.

Rham stood there with his hands in his pockets, nodding, worried about whatever he needed to worry about—the possibility that they'd review what Anne had seen, what I'd said to her. He could have ripped her head off and stashed it somewhere, but he didn't. He nodded when they said thank you and held me to him when they hauled her away, knees folded up, in a plastic box.

He brought me to school the next morning and I had to pretend that everything was okay—as far as everyone knew, Anne was just gone.

At lunch I saw Lucy, the third artificial, sitting by herself at the corner of a table. It was a lonely picture—I wondered how she felt about Anne, whether Lucy was also feeling the existential dread sifting through her algorithm.

I was thinking I should say something to her—some kind of consoling word or two.

But just as I was starting in her direction, a group of kids sat next to her with their lunch trays. The blank look she wore became a smile. She talked, and I watched for a moment after receiving my tray, getting into the line for my food. The unconcern on her face. I wasn't very good at reading people to begin with, so it might not have been anything—she didn't seem affected. She had a job to do. She never spent much time with Rosy or Anne anyway, so why should she care?

I was about to sit at a table alone at the corner, near the doorway, under the sound of the air blowing machine at the door where all sound was drowned out from the room and I could feel at peace with myself for a moment when I found myself drawn to Lucy's table anyway—I didn't sit right next to her but by one of the other human kids. We didn't speak. We barely acknowledged one another. I just listened to them for a little while talking about the birds they'd seen, some video game or movie, I couldn't tell which. I didn't do anything but listen, but it felt like enough.

Content warnings: Death and dying, neglect, alcohol use, drunk driving