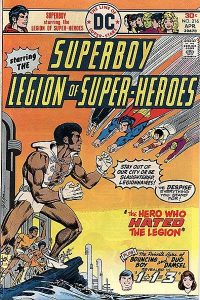

A past’s vision of the future can teach us something about its present, or, in the case of the “Big Two” superhero comic book publishers, about how it ever was and sometimes seems like it ever will be. Issue #216 of DC comics’ Superboy, Starring the Legion of Superheroes enlightens readers not only on the state of race relations in the idealized 30th century of its stories, but captures the arc of most black superheroes in the comic book world, whether it be in 1976 (when issue #216 came out), or the 2000s when Luke Cage joined Brian Michael Bendis’s New Avengers.

In “The Hero That Hated the Legion” readers are introduced to Marzal, an island city populated by “a Black race that wants nothing to do with the outside world” and their bare-shirted champion, Tyroc, whose various cries and grunts grant him a strange collection of superpowers. Forced to enter Marzal in order to seek out stolen goods that have crashed to Earth from where they were hidden in a satellite (and that some bad guys are after), Superboy and the Legion of Superheroes find themselves unwelcome. Needless to say, all of the Legion are white—even when they are green (Brainiac 5) or blue (Shadowlass), they are white. Biracial Karate Kid is the exception, but since his ethnicity comes in the conveniently helpful form of martial arts, and he unquestioningly accepts the superiority of the dominant culture, there is no problem with his being part of the group. The visual nature of the comics medium marks blackness as different. Thus Tyroc and the people of Marzal are another story.

At the behest of Tyroc (whose afro’d visage appears on huge tele-screens around the city), the people of Marzal avoid the “Legionnaire intruders,” refusing to talk to them and ducking into their homes. Tyroc’s fiery rhetoric accuses the Legion and thus the outside (white) world of purposefully ignoring Marzal in its times of need. He gives a litany of times that the people of Marzal needed help, but the Legion never offered any. The neglect these people of color have experienced is not meant to remotely challenge the rightness of whiteness, which the narrative presents as self-evident, but to indicate Tyroc’s unreasonableness. When Tyroc mentions how the Legion failed to provide aid during the “terrible ion storm of last spring,” he comes off like Kanye West in the eyes of white America admonishing George Bush on live TV during the Hurricane Katrina fundraiser—Superboy doesn’t care about black people, either.

Sure, this comic came out 30 years before Katrina, but the effect is the same. How dare Tyroc assume that anything but the ill-fortune of choosing to live in this city led to their situation? How dare he mention it? History is meaningless because “racial prejudice died out centuries ago.” Any resentment that Tyroc and his people feel must be unreasonable bitterness. Both blue-skinned Shadowlass and Kryptonian Superboy remark on just how “bitter” Tyroc sounds. In fact, when the Legionnaires discover that Tyroc is trying to capture the same bad guys as they are, Superboy says, “He’d better not get in our way!” because the sovereignty of the black people of Marzal doesn’t mean shit to the Legion. Tyroc asks, “Is it the color of our skin that doesn’t make us important enough?” Despite the efforts of the story to suggest otherwise, the answer is fairly clear: Yes.

Superboy and the Legion of Superheroes wants readers to understand how ungrateful black people are for the help they do get. When a couple of Marzal’s citizens are saved from a bridge collapse by Superboy and Karate Kid, the narration asks “But do the survivors express gratitude?” as the panel depicts them yelling “Get out or Marzal!” and “We didn’t ask you to save us!” Karate Kid characterizes this as Tyroc “brain-washing them with hatred.” The Legion never considers whether Tyroc’s accusations might have merit, and clearly neither does the author (given the resolution of the story.)

After Superboy and the Legion defeat the bad guys and rescue Tyroc and his city, Marzal’s champion is confused. “You went out of your way to save my life…even though we’ve shown you nothing but hatred and contempt!” Superboy explains, “When it comes to race, we’re color-blind!” Shadowlass and Karate Kid add, “Blue skin, yellow skin, green skin…we’re brothers and sisters…” Tyroc is convinced! Realizing he’s been “wrong about a lot of things,” he agrees to return to Metropolis with the heroes to see if he qualifies to become a Legionnaire. “Long live the Legion!”

Marzal would then be mostly forgotten until Tyroc and the Legion return four years later. At that point it was in danger of phasing out of this dimension for 200 years, putting black people even further out of “the world” the Legion saves.

Tyroc is limited to Marzal by choice—as a result of his own hatred and ungratefulness—until the magnanimity of the Legion of Superheroes shows him the error of his ways. The fact that his land and people have been ignored by the Legion until now is never addressed. It is obvious why. The reason lies not in the narrative within this issue or even in the continuity of issues of Superboy Starring the Legion of Superheroes, but rather in the narrative of white supremacy that is implicitly part of the superhero genre. The reason Marzal is ignored is because writers and artists in our world could afford to ignore people of color. When it became increasingly difficult to continue that neglect, well the reason has to be not the fault of those being neglected, out of their prejudice.

This whole story is the 30th Century equivalent of that old saw, “Who’s the real racist?!”

This overly-didactic, problematic comic might be easy to dismiss as a hackneyed exception from almost 40 years ago. However, we can point to DC’s slightly less didactic introduction of John Stewart, as back-up Green Lantern just a few years before. And we can see what the competitors at Marvel were trying to do with the afrofuturist pretensions of Black Panther or the Blaxploitation verve of Luke Cage in the same decade. Whatever the setting, all these comics and characters sooner or later fall into the pattern laid out in this one issue of Superboy .

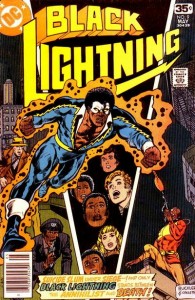

A year after Tyroc’s appearance DC comics would have their first title featuring a black superhero, Black Lightning, whose focus was on a Metropolis ghetto where Superman is never seen—Suicide Slum. There is something to be said for a black superhero who focuses on helping his own community. But when the reason that his community goes ignored by other (all white) superheroes remains unspoken, it is difficult to ignore that segregation matters in the superhero universe. It is a classic double-bind that black characters are placed in. They can either focus on helping their own, which leaves them marginalized (and in the case of Black Lightning cancelled after 11 measly issues), or develop more of an audience through mostly ignoring their cultural or racial heritage—their blackness serving the purpose of representing diversity without actually being diverse. Blackness, like the “black” in the hero’s name is just part of the pattern of superhero costumes that serve for easy and broad identification. Later, Black Lightning would be recruited into Batman’s Outsiders where his race never became much of an issue and would eventually lead to his becoming Secretary of Education for the Lex Luthor administration—Suicide Slum forgotten.

Marvel’s Black Goliath had it even worse. His series only last 5 issues, and in those five issues and in his guest appearances in other places afterwards he is mostly depicted as an inept superhero. Rather than being relegated explicitly to a black neighborhood, BG’s own title took place on the west coast, which in the Marvel Universe is just one step above being a Great Lakes Avenger—it is where failed or second-tier comics go to die. Furthermore, he is depicted as growing up in Watts, a black community in Los Angeles, providing his blackness some “street cred,” even as his profession as a scientist for Stark Industries marks him as an exception. Black Goliath would never really make it into the big time. He’d briefly be part of the Champions (who?) and later the West Coast Avengers. Eventually he was served up as a sacrificial lamb on the altar of the summer crossover event in 2006, when he’d be killed by a clone of Thor during Civil War. The subsequent outrage of his heroic peers was out of proportion to his actual role in the comic universe.

Even the more successful black superheroes are enmeshed in narratives of assimilation, or at the very least prioritizing the values of a world that would dismiss them over their own. Luke Cage, aka (Black) Power Man, inhabited a marginal space in the Marvel Universe for a long time. Both his insistence on getting paid (his original title was Hero for Hire) and the fact that he operated out of an office in the seedy Times Square of 1970s New York City, marked him as different from the mainstream Marvel heroes. And when the Blaxploitation fad that spawned his character began to fade, another character, Iron Fist, was bumped into his book, so that he and the wanna-be Asian-appropriating-kung-fu-superhero could continue to limn the edge of a world dominated by Captain America, Iron Man and even Spider-Man (I guess folks could tell he was white under his mask), until cancellation in the early 80s. It would not be until the early 2000s, after a failed gangsta rap influenced relaunch in the 1990s, when Cage would be invited into to join the New Avengers, that he’d make good. There is a scene, however, that cements his journey from a seedy “for hire” world to the world of the Avengers. He convinces Captain America and his fellow Avengers to perform “impact superhero work” in emulation of the NYPD policy of the Giuliani and Bloomberg eras, in which high saturation of a “bad neighborhood” with police ostensibly leads to a lowering of the local crime rate. In New Avenger #17 (2006), Cage brings superheroes to what seems like a modern-day-Marzal, Detroit—ignoring the history of white flight and loss of industry in favor of a narrative of black criminality. Luke Cage agreed to join the Avengers if he could do some things his way and different from the status quo, but he is actually just recapitulating tactics that unfairly target marginalized people, while Iron Man and Captain America patronizingly approve of Cage’s articulate display when interviewed by the media. Cage points into the camera and issues his warning, “We’re coming to your neighborhood,” We all know who that “your” is. The job is done. Luke Cage is legitimated and those neighborhoods he claimed to want to use the Avenger’s resources to help? They are never mentioned again. They might as well have phased out into another dimension like Marzal.

Of all well-known superhero comics, perhaps only Milestone’s heroes managed to re-imagine the superhero world as anything other than white—and we all know what happened to them. (And if you don’t know, and are asking “What’s Milestone?” then that is answer enough.)

The world of superheroes remains unrepresentatively white. Its characters must adhere to the confines of that culture. Black superheroes must serve as a stand-in, representing all their people not for the benefit of those people, but in order that their white peers remain virtuously color-blind. “Black” skin must be just like “green” or “blue.” Green and blue people aren’t real. Black culture, history, and community are not allowed to be real, either.

Marvel editor Tom Brevoort tweeted in 2011, “99% of all superheroes are white." This conflates the reality of the published world with the world it is to some degree meant to represent. Less generously, Brevoort’s statement accepts that to whatever degree comics present an idealized world, the ideal is predicated on there being a lot fewer non-white people. Our fantasy erases people of color, either by assimilation or by literally banishing them to other dimensions.

Maybe Tyroc and the people of Marzal had the right of it in 1976. Better to opt out and refuse to participate if being counted in the fraternity of superheroes means having to pretend the superhero world has already achieved racial justice.