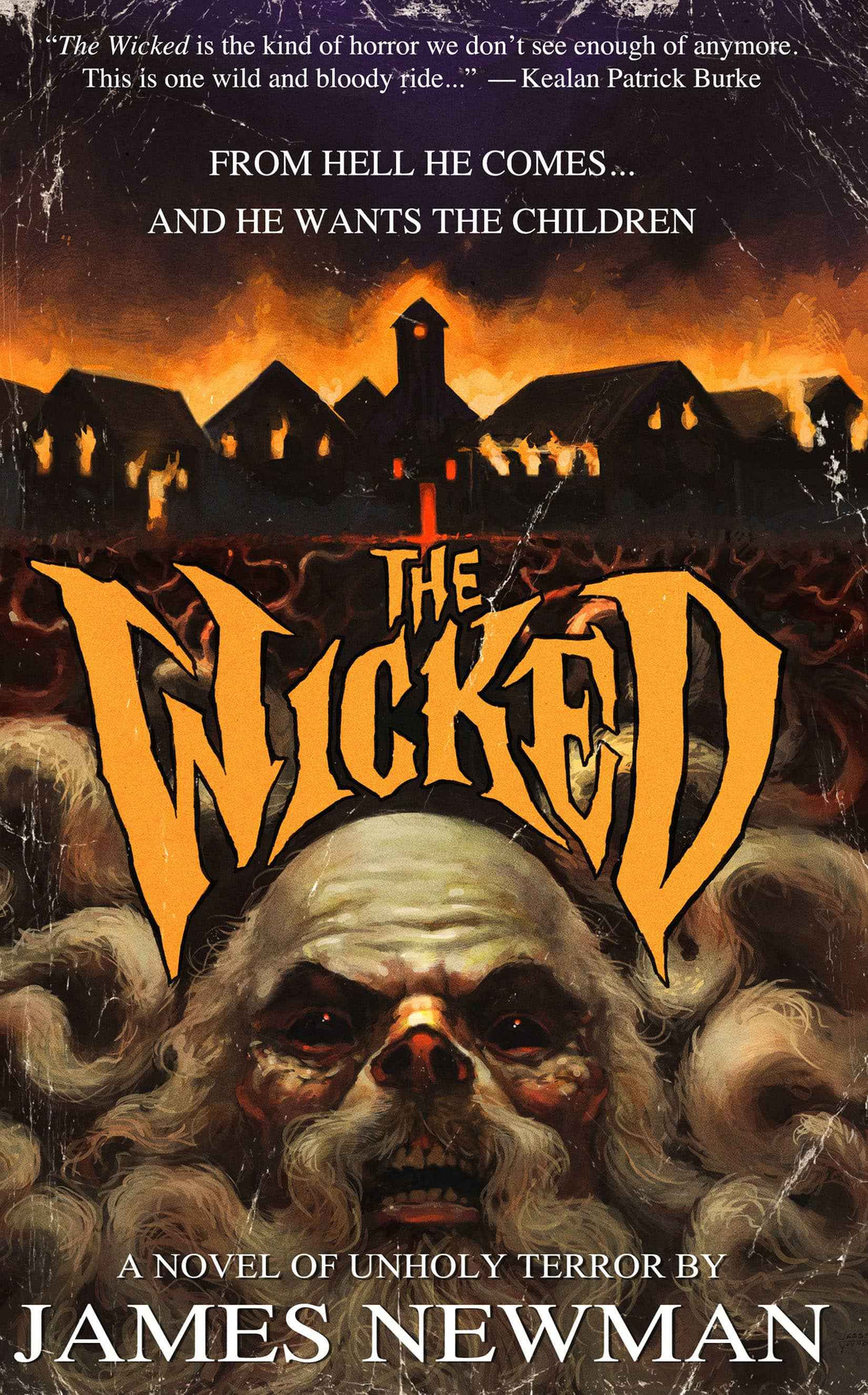

The Wicked (Excerpt)

by James Newman

On the evening of August 12, 2002, a fire raged on the outskirts of Morganville, North Carolina. Into the early hours of the morning it raged, higher and higher, as if the flames fought to devour the moon itself along with everything else. Because of the Morganville Daily Register, the tragedy of that night would come to be known as “The Great Fire of ‘02,” and its casualties would haunt the citizens of Morganville for the rest of their lives.

Neither ghosts nor spirits were these haunts, but instead the collective disbelief that such a thing could happen to the town’s innocent.

It happened at the Heller Home for Children, out on Pellham Road.

*

Initially the Morganville Youth Home, Heller Home was erected in October of 1952, ninety years to the day Morganville was officially established on paper. Founded by Joseph and Irene Heller (a retired Episcopal minister, he was known as “Uncle Joe” to the kids, she as “Aunt Reeny”), the place began as a modest two-story farmhouse, by all outward appearances little more than the quaint country home of a typical Southern family. Inside, however, one would find a house full of love and tolerance, a bustling home for children of every race and creed. No less than a dozen kids usually roamed Heller Home’s hallways, playfully roughhousing under Mr. Heller’s watchful eye while less rowdy teens nurtured their artistic talents with brush and easel. Within this makeshift haven for runaways and the like, Mrs. Heller cooked for her young wards nutritious meals which they might otherwise lack, and eventually the kind-hearted couple would convince these prodigal sons and daughters to return home to their families.

Within a year or two the Morganville Youth Home evolved into an unofficial hospital for neglected and abused children. Mr. and Mrs. Heller were not licensed medical professionals, but thanks to their close relationship with the Morgan County Department of Social Services they were granted funds enabling them to hire several qualified bodies eager to aid them in caring for poor children with nowhere else to go. Although the official licenses and such did not come until a year after their deaths (Mr. Heller died of a heart attack at the age of seventy, Mrs. Heller four years later of natural causes), the Hellers’ dreams were nonetheless posthumously realized. Six months after Mrs. Heller passed away in the first days of Spring ‘79, Morganville dedicated the new “Heller Home for Children” to the couple. It officially opened its doors as a government-sanctioned hospital to not only victims of abuse but also to children from needy families, particularly youth with chronic illnesses. Due to its historical value, the powers that be resolved not to raze the house and begin anew; instead, volunteers and county workers donated their time and money toward adding several new wings onto Heller Home. A local land developer, claiming the Hellers were the only family he’d ever known, dedicated three acres to the hospital and its young wards. There, the children could run through the grassy meadows bordering Morgan County, wade in the creek or climb the grand oak trees that lined the property.

It seemed as if every person in town did all they could to support the Home, be it through donations or by contributing toys or clothes, and Morganville’s citizens did this not out of pity but from the goodness of their own warm hearts.

Uncle Joe and Aunt Reeny would have been proud.

But on the night of August 12, 2002, two months shy of its fiftieth birthday, no one could have expected that the Heller Home for Children would suddenly ignite.

And burn.

And burn.

Until there was nothing left.

*

The Morgan County Fire Department received the call at approximately ten-thirty p.m. The caller: one Marietta Rude, an eighty-year-old widow who had nothing better to do, according to most who knew her, than track the whereabouts of others so her bridge club might have ample fuel for gossip every third Saturday of the month. Mrs. Rude had lived across the street from Heller Home for decades, and many could remember the days when she had branded the Home a haven for “no-good runaways.” Of course, to hear the old woman after The Great Fire of ‘02, it had been her duty to watch over those poor children since Heller Home’s inception. Things had been slow for Fire Chief Randall Simms and his crew that evening—“like the calm before the storm,” they would later tell their friends and family. Frank “Beanpole” Deon was kicked back on a sofa in the center of the firehouse, chomping loudly on a meatball sub while flipping through the latest issue of Popular Mechanics; Jack Deese and Ricky Friedman entertained themselves with some late-night Cinemax softcore on the Department’s 13” Magnavox, occasionally making off-color comments about the women on the screen out of extreme boredom more than any desire to be vulgar; Chief Simms, meanwhile, was engaged in a game of chess with Hank Keenan (who, in addition to volunteering much of his time at the firehouse, also served as a Deputy Sheriff and president of Morgan County’s Dads Against Domestic Violence chapter), both of them too bored to admit that neither could beat the other no matter how hard he tried, so why bother?

Simms had just taken Keenan’s bishop, the only move of any significance to occur in their half-hearted charade for the last hour, but the Chief never had time to gloat about it or even remove the piece from the board as the station’s ear-piercing bell suddenly announced it was time to move. Its shrill ring echoed throughout the halls of the firehouse, shattering the calm. A sleepy female voice on each man’s two-way radio informed Simms’ crew of their destination.

“Move your asses, boys!” Simms yelled, already sliding down the tarnished brass pole in the center of the room. While rookies Deese and Friedman were half his age, Simms could hustle twice as fast as either man; experience had taught him every second was precious. “Move, move, move!”

*

Chief Simms and his men responded in record time, sirens screaming and lights flashing over the sleeping gray houses of Morganville in their wake. But Heller Home could not be saved. The house’s main supports had already collapsed by the time they arrived, and no matter how many gallons of water they used to douse the place, Chief Simms and his men found their efforts were ultimately futile.

Simms cursed himself more than once that night.

He realized, before long, that they could do little more than stand there.

Stand there, watch the place burn...and pull out all the bodies.

*

The final death toll was sixty. Thirty-seven children dead. Eleven more seriously injured. Six of Heller Home’s care-supervisors who were on shift that night perished in the fire; the others were in critical condition. Of the twenty-odd residents who did make it out of Heller Home alive—be it through the aid of Chief Simms and his men or their own iron will to survive—seventeen of them later succumbed to their injuries.

The Great Fire of ‘02 was the worst tragedy Morganville had ever witnessed.

Several days later, after the mass funeral that saw Morganville citizens shed more tears in a single afternoon than they ever thought possible, Chief Simms and a couple professionals called in from the state capital determined that The Great Fire of ‘02 was no accident.

Someone had caused all that death, all that destruction, on purpose.