I don't do flash fiction.

Charles Stross

Just like painting a one-inch miniature portrait inside a seashell is harder than painting the same portrait on canvas as large as you like, writing flash fiction can be a challenge. It forces a writer to refine their craft to a sharp point. Flash fiction needs to have everything a short story has—characters, twists, tension, resolution—but it has to do it in a cramped space. There’s no room for waste.

Story Basics

What are the bare minimum elements of a story? Let’s take a look at a very short story:

Three men walk into a bar. The fourth one ducks.

Jokes are stories. The first part of this joke establishes its genre – “man walks into a bar” jokes. The second sentence subverts the expectations established by that genre, creating a twist and conclusion.

Stories create tension, and then they resolve it. For your flash piece to work, it has to give the reader something to care about, then make them tense about that thing—worried or hopeful or afraid – and then resolve that worry or fear.

One of the major reason flash stories fail is lack of structure. Lack of a twist, turn, or satisfying conclusion. There’s no need for more than one twist, no space for complications, but the story absolutely must feel like a comprehensive whole, and having a conclusion goes a long way to making it feel finished. You want to leave the reader with a feeling that a door has closed, a purse snapped shut. The whole is complete.

It doesn’t have to be complicated, or new, or different. Every day someone falls in love with their first epiphany story, happily-ever-after romance or butler-did-it mystery. Structures are shapes we pour stories into. It can be as simple as: Introduce a character with a problem. They try to solve it and this complicates the problem. They try something else, this works. Think of how many different stories can fit in that vessel. A secret agent, a bored toddler, a con artist, a saint.

Flash Fiction Tips and Tricks

If you’re here for tips and tricks, here are mine. I start with a story seed. Maybe it’s a character I want to write, or an idea, or an emotion. Maybe it’s a setting I want to share with the world. The Velvet Tango Room, a speakeasy tucked down a blighted urban street with broken weed-choked sidewalks. Let’s start there.

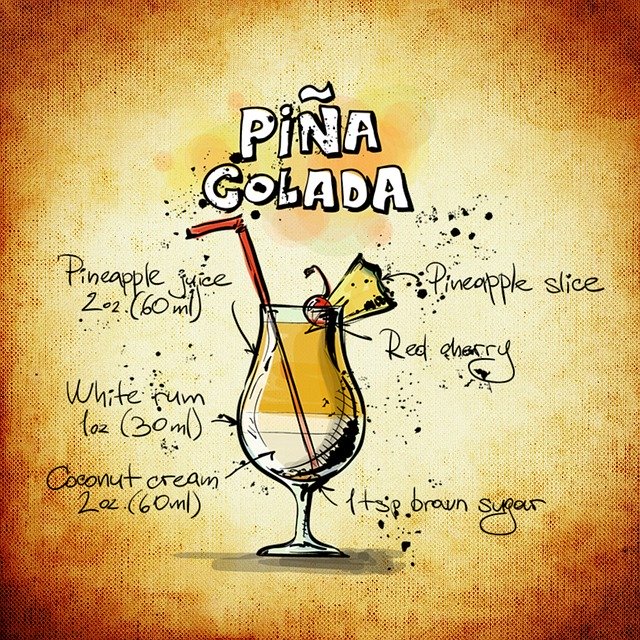

What is that satisfying ending I want to leave the reader with? How their gin martini will make you wonder what garbage you’ve been calling gin martinis all these years? Okay, it’s a story of discovery. I write down my ending, the discovery. Then I pick a false lead, a false discovery, that goes in the middle. I’ll open with you pulling the heavy wooden door.

A recipe for flash fiction: setups, twist, and punchline.

A recipe for flash fiction: setups, twist, and punchline.

Because flash is so short, I often think in threes: Setup, twist, punchline. Sometimes, if I’m really lucky and careful with my word choices, I get a second twist in the second draft.

Here’s a twist: It’s awful in the Tango Room tonight. Crowded with smug-looking twenty-somethings wearing clothes that cost more than your apartment. The date you wanted to impress looks ready to fake a family emergency.

It’s good to start with character, with a person the reader can inhabit. Someone we can care about. Why are you dragging your disinterested work colleague to this speakeasy?

And when I say character, I don’t mean physical description, job title, or a list of super powers. You might want that stuff in a longer story, but flash demands brevity, so only give us the most interesting detail about this person. My teacher once said “If you mention a character’s hair color on the first page, you have nothing interesting to say about them.”

Stories work through emotion, and a flat detail, no matter how plot-relevant, won’t engage your reader. It’s not that the narrator can speak to the spirits of the dead, it’s that they’re afraid the dead think they’re an alcoholic because they’re going to a bar on a Tuesday. As another teacher told me, “Write the dirty, messy things your character hopes no one notices about them.”

I like my one detail about my flash character to be a contradiction. The brave coward, the quiet blabbermouth. What is your main character’s innate illogical mix? Can you reveal it in one sentence, preferably an active sentence?

You drag your date into the crowd, wanting to explain the history hidden behind jostling shoulders, wanting to explain the mysteries enacted by the women behind the bar, but only arrogant jerks lecture. You hope your date will give you a chance to lecture.

Or it’s not that kind of story. Maybe you’re writing a straight-up action piece and all that matters about the protagonist is that they are in trouble and need to get out of it. That’s okay, too, but make the trouble interesting, and make their reaction to it not the first thing that comes to your mind, but the second or third.

There’s less room for character if you need to fit an action plot in under 1,000 words. Every element that needs explanation takes space, so if you have ghosts you might not have room for undead policemen. It’s a choice. Sweet or dry vermouth? An olive or a cherry? A martini and a Manhattan fit in the same glass. You wouldn’t drink them mixed together. (Blech). Let your flash piece do one thing well.

Flash Fiction Rules

I’m a big one for rules. I make them up and I steal them from other writer’s tweets and blog posts. Here are a few:

If you describe something twice, compare the two descriptions. Delete the less interesting one.

Create a setting with one image. A fireplace is a living room. A pile of leaves a yard.

Delete every cliché. There’s no room for that in flash.

That said, nothing like a good stock character to let your reader fill in gobs of background with nary an extra word from you. Pour some whisky and antacid together and you’ve got a grizzled detective.

Write the worst first draft you can, because it’s a thousand times easier to edit than a blank page.

Here’s how I write terrible first drafts: Lay down the bare bones of your story structure. Start with one sentence. Two sentences, three. A man walks into a bar. The bar is haunted. The ghosts are more interested in the cocktails than him. Replace each sentence with a paragraph. Edit the paragraphs into scenes or plot beats. Add that spicy dash of theme. Replace your sentences with better ones. Writing is re-writing.

Maybe you aren’t starting fresh. Maybe you have 800 words you scribbled down in an inspired fit, half-drunk after that fateful worst/best date, and they are lovely words, but you can tell they aren’t quite a story yet.

Push those words around. Find the strongest, most emotional sentence in the piece. That’s your new last sentence. Find the second strongest. That’s your new first sentence. Can you make this work? Did you just ruin it forever? Hell, that’s what saving a new draft is for. Write bits on Post-it Notes and move them around on the desk. See what feels like a story. Push the middle emotionally away from the rest so the story has movement. Foretaste of smoke, caramel on the tongue, finish with peat. Make a good thing bad, a bad thing good. Lie.

Trimming the Excess

If your story is too long, delete every instance of these words: Seems, almost, nearly, merely, really – any words that express your inborn need to caveat. We know there wasn’t literally every type of drink on the menu, but it’s okay to say “every type of drink” instead of “almost every type of drink.” I promise it’s not cheating.

Also delete: So, very, a lot of, a bit of, a little. Unless you need that beat to force a pause. Interrogate extra words, ask them to justify their place in the story.

If your story is still too long, see if there are actions you can move next to dialog to stand in for dialog tags, replacing “he said” with “he sat down” if you already had it. Yes, this means having a character sit earlier or later than originally planned. There are few actions so precious they can’t be nudged.

If the story is still too dang long, well, you may have to remove a scene, or a character. Pick through the story’s parts, find the organ that’s not pulling its weight. Ask it, are you contributing to the emotional payload I want this story to deliver? Ask the barstool, the quirky customer, the loving description of the burning of a sprig of rosemary: does this story stand without you? If so, let me show you the door.

The Final Cut

Be messy, be vicious, be specific and immediate. And cut, my darlings, cut like a sadistic casting director, and you may just get that perfect glassful of story.