We drive iron nails through my sister’s feet and into the dusty floorboards below to keep her from flying away. She cries and rages, but one wrong move—a single fall—and her knobby knees will snap in half like saplings in a storm. I am tasked with caring for her in the aftermath. Sitting her down on a low stool. Wiping her tears and telling her it’s for her own good.

My twin spits into my eye. The foam coagulates against my lashes. “The angels chose me as their familiar. Me!”

Me, and not you.

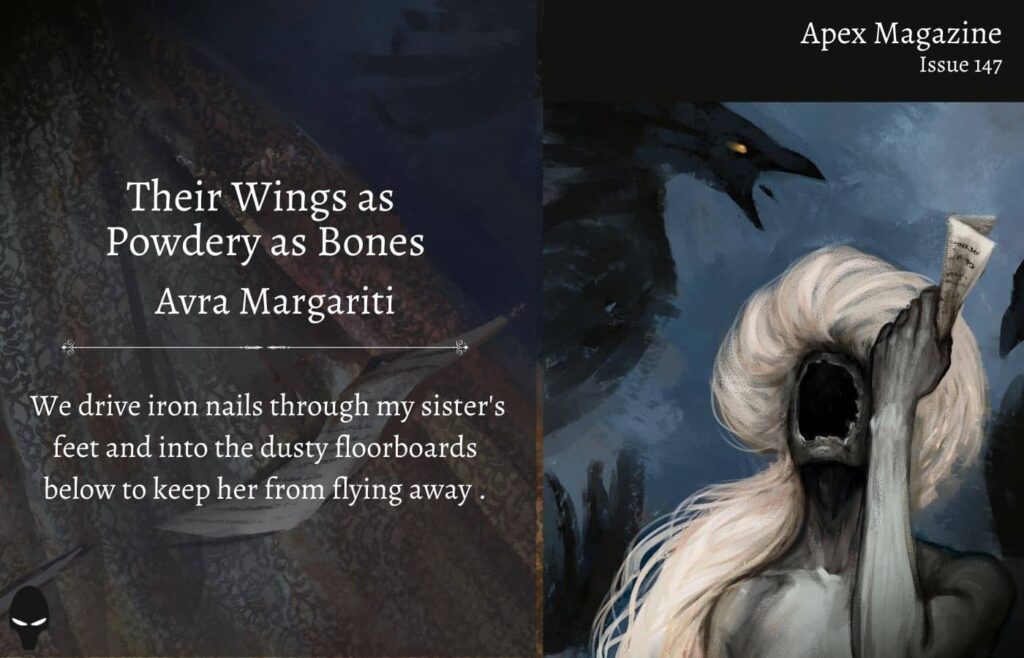

I gaze out the window where giant moth wings tesselate our front lawn, and bone-powdery stardust coruscates in the watery sunlight. When Mother beholds the roiling shadows, she firmly closes the drapes. Her mouth tilts, like stitches are pulling it down into a marionette moue.

My sister strains against the bloody nails toward the window, and the fuzzy shadows beyond. She doesn’t care about the pain, or, perhaps, she even revels in it.

Once upon a time, we are twins, and we are six years old. I’m nine minutes older than my sister, but it is always her who chooses which game we play each today.

Today we’re in the garden, and the game she’s chosen is crosscut-the-angel.

My sister’s made me grab a net and gather moths and butterflies for our game. Their powdery wings flap uselessly against the frayed rope of the net. Then, my sister bids me to trap the insects in an emptied marmalade jar. I can’t tell if the residual redness around the rim of the jar is strawberry preserves, or bug blood.

My sister does not like to use any type of tool or blade. Only her own chubby child fingers. She makes me hand her each moth, each butterfly, like she’s the doctor and I, the nurse.

Makes me watch as she tears off the wings. Brown and furry, or bright and variegated. One by one, stitch by stitch, she unravels them.

Sometimes she shoves the wings into her mouth, claims they taste like candy. The bent, disembodied appendages get stuck between her wiggling baby teeth. Other times she simply crushes the wings inside her fists. Always, she asks for more specimens to cut apart and examine.

Yet now, at sixteen, every time someone on the local news station mentions shooting one of the angels dead, my sister screams herself raw and tries to escape her binds until the smell of iron lingering in the house is joined by the copper tang of her blood.

The collective noun for starlings is a murmuration. For crows it is murder. For angels, I think it should be loss.

A loss of sisters.

Mother and I walk fast and furtive down the street, after visiting again with the holy man who ordered we keep my sister captive until the angels’ compulsion wears off. We rush homeward, having left my sister alone, her hands bound as well as her feet so she wouldn’t deal any more damage to herself. Normally, I would have stayed behind to care for her while Mother went to work and to the ever-emptying stores. But today, our mother woke me up and dragged me by the hair to the holy man, after a dream she had of me levitating.

It wasn’t worth the backhand to tell her that my sister and I share a face. That it could have been her as easily as me floating away into outer space in Mother’s dream.

After the holy man examined me, he pronounced me flightless, grounded, safe. Mother rejoiced, but my heart felt more leaden than my limbs keeping me solidly on land.

On our way through the neighborhood, we pass other children out with their parents, walking among the debris—several telephone poles and buildings had collapsed when the angels first alighted over our town. Some children are made to wear iron shoes as their parents pull them along under the brown-winged dome. Overhead, the angels mantle magnanimously in overlapping wingspans. The angels have no human characteristics, unless you squint. Then you might be able to make out a pareidolia face in the fuzz of their forewings or hairy heads. The face may or may not be screaming.

Some say the angels are not sentient; others, that they possess superior intelligence. The only thing we know for sure is that when they showed up, some people—some children—began to levitate towards the static stratosphere of the angel dome.

We walk on, Mother’s grip a vice around my forearm. Some parents prefer to slap handcuffs around their kids’ and their wrists, linking them together. The other day on the news, we watched a handcuffed mother lift off after her floating daughter, dangling midair until her shoulder joint dislocated, then her palm split apart. She fell and fell and fell toward the unforgiving asphalt. Her daughter tilted her head skyward, awash in elation, and never once looked down at her struggling, shrieking mother.

Along our street, little hands bang against the windowpanes of neighboring houses, begging to be let out.

I look up at the angel dome, trying to focus past the illusion of screaming faces; see if there are any children caught in the wings’ sunset-brown chitin. It is believed, once the angels have caught enough children like butterflies in nets, they will fly away back to where they came from.

Mother, fumbling with the house keys, catches me looking up and harshly pinches my side. The bruise will form right over the ribcage, straining with my every breath. From the other side of the door, my sister is howling. With waning patience, Mother pinches me anew when she realizes I forgot the gag.

Symbiote:

noun

a person living in symbiosis with another

organisms of different species peacefully co-existing in a mutually beneficial arrangement (e.g.: feeding, grooming, hunting)

an angel and an angel’s familiar

While she was burning with fever, this is what my sister accidentally confessed to me: the job of the chosen children is to pick the angels’ wings clean of space litter and ethereous pathogens. The wing fuzz is really scales made of keratin, carbon, and whatever dark-matter substances the angels carry with them from deep space.

Though twins, I was always larger than my sister. I wonder if my cumbersome bones are why the angels didn’t pick me to float. To fly. But my sister’s grace is lost now. Her hair unwashed. Her skin dirtied. The bucket she uses for her daily waste spilled all across the walls in one of her outbursts. A mad glint foxtrots in her eyes, distant like she is already soaring. Already picking comet- and space-dust from the angels’ bone-powdery wings. To think that the cherubic sister who once tore wings off lepidoptera now wants to spend the rest of her life caring for the moth wings as they cradle her in chitin …

I fall asleep in the bed my sister and I once shared, missing her body heat. I am alone, no wings to enfold me in their unknowable depths. Morning comes dark and sudden, sunlight filtered in grayscale through the angel-wing dome. I rub the grit from my eyes and trudge to the living room, following the sound of muffled grunts.

Mother is trying to wash my sister’s hair where she still sits embedded like furniture into the floor. The matted locks glint wet and soap-studded, the water basin lying upside down next to my sister’s inflamed feet. I huddle in the doorway, watching our new morning routine unfold. Frustrated, Mother kicks the basin away and next focuses on force-feeding my sister gruel from a child’s plastic bowl. My sister has refused to eat ever since we introduced her to the ironclad necessity of her confines. She chokes and splatters with each bite of food pushed between her lips, bile rising acidic in her throat and mine.

“Every angel is an alien,” Mother viciously recites. These are the words the holy man assured us will ward our household against moths and madness. Mother digs her still-soapy fingers into the gruel then shoves them into my sister’s mouth while her free hand pries the recalcitrant jaw open. I wonder if next I will be asked to wire my sister’s mouth closed or open at Mother’s will.

Sometimes, when my twin struggles, I think I can feel the pain in my own feet as well, the grinding bones and squelching flesh, the way womb-symbiotes are said to share sensations.

“Come here and help me,” Mother barks when she spots me in the doorway.

And I do, but before I can reach my sister, she’s bitten the finger Mother has forgotten in the cavity of her mouth. She digs her teeth in so deep, she must reach bone. Mother yelps, irate at the hubris of my sister mutilating her the way we have done to her.

For your own good, it’s all for your own good.

Mother slaps my sister across the mouth. By then, my sister has flexed upright as well, her footstool lost in the scuffle. The chains around her wrists pull taut. She wobbles, and the iron nails bite further into her inflamed feet. Sending spurts of pus gushing out with each sway.

“I cannot deal with you girls anymore,” Mother says and, rushing past me, she shoves the bowl of half-spilled gruel into my hands. It stains my secondhand nightdress like baby’s spit.

I remember what Mother had told us after Father’s death: I will never let you girls go. Not to marry. Not to study in a different city, or even to work far from the neighborhood. We would only have each other, she said, locking the door, swallowing the key. My sister raged, but I was secretly relieved. So perhaps, though we are twins, this is another reason why the angels chose her and not me. She wanted to go, and all I knew was how to stay.

“Let me go,” my sister says conversationally when I resume her feeding after Mother has locked herself in the bathroom. Her voice is hoarse from choking, from screaming.

“What will you eat up there,” I ask, “if I let you go?”

How will you feed yourself, living on the angels’ wings like a parasitic entity? How will you survive what lies past the earth’s atmosphere?

She scoffs. “Dewdrops glinting off glorious moth wings. Bugs caught in the angels’ antennae. Sun and wind and stardust. The celestial music of the spheres.”

My sister’s chains rattle as she says this, suddenly animated despite her recent fever stupor. A sneer paints itself across her bitten lips, as if she’s disgusted by my mundane questions in the face of the profound summoning that thrums through her veins.

I think of the pliers in the shed that would remove the iron nails from her feet. The cutters that would rid her of the manacles around her wrists. We locked the cuffs there after she kept trying to remove the nails with her own. But I will never bring the tools of my sister’s freedom, her flight, back here. A revenge—but for what?

“I just don’t want you to get hurt out there,” I say. My lie curls wisps of shame down my spine as I stare down into the haruspicy omens of the congealing gruel.

My sister laughs like grating planetary rings. “You groundling,” she says with a pity so immense, it contorts my insides.

It sounds like: you will never understand.

It sounds like: you will forever be left behind.

At school we practice making protective armor out of the scrap metal we scavenge from the debris the angels left in their landing. We study the proper antiseptic care for open wounds while the foreign object is still inserted inside. How to walk in the street in zigzag patterns so the angels cannot swoop down and grab us if they ever tire of their placid sleep and decide to take matters into their own beaks.

I look around my class, left as bare as the grocery store’s shelves. More and more chairs are empty every day. More and more children answer the angels’ call.

It’s easy for pathogens to enter the bloodstream from an iron wound, the teacher writes on the blackboard. The roads have been closed off since the angels landed over our town, enfolding roads and paths in their bone-powdery wings. The supply and trade routes are all cut off. No more antibiotics left, but at the first sign of fever or delirium, my teacher says, here are the herbs you can forage from the ravaged roadside.

Here are the holy man’s prayers to chant and hope for the best.

Dinner is old marmalade and the last of the bread we had stored in the fridge.

Mother’s finger is still bleeding from my sister’s bite. It has been weeping blood, on and off, for days.

We sit at the table together, my mother and I, and we eat silently, not tasting each bite nor looking at each other.

The marmalade jar reminds me of the moths and butterflies I once trapped at my twin’s behest. Perhaps this is another reason why the angels shun me now. My sister did the ripping, but it was I who did the capturing.

My sister cannot scream now because of the old doily occupying her mouth in a makeshift gag. Still, her grunts rake our ears through the closed door. Do the angels hear them, too? Is this a test, to see if my sister wants to answer their call bad enough?

I look at my moldy bread and think I can discern broken insect wings emerging from the red mounds of rotting strawberries. I look at my mother’s flimsy slice. It sits on her plate uneaten, a lost expression in her often-cruel eyes, not seeing how the blood from her wound drip drip drips into the red preserves. Until blood and strawberries are one.

In the middle of the night, I am dragged to wakefulness by the great flapping of wings. Heart chained to my throat, I rush to the living room, only to find the manacles lying limp on the floor, the iron nails still driven through the scratched floorboards. Yet my sister is missing. The only remnant of her: the meat and blood and chips of bone clinging to the iron where she freed herself.

She must have dislocated her thumbs to escape the cuffs around her wrists. Her dainty feet too must be ruined for good, but where she goes now, she won’t need them.

I don’t wake Mother up. My own intact feet lead me outside, to the dewdrop-chilled lawn. I expect to see my sister levitating and luminous like a fallen star in reverse. I picture myself clinging to her blood-slippery feet. Telling her to please, we’re of a face, of a womb, please take me with you.

Except, the sky is devoid of the dome of moth wings that has been shading our town for weeks. The moonlight skirts over our overgrown lawn unobstructed. Whatever escape happened, whatever covenant was sealed between child and angel, I was late enough to miss it. And still, as I fall to my knees amid the gritty grass, I can’t help but picture my sister floating up while marmalade-blood rains down below.

In my mind’s eye, she reaches out a yearning hand towards the dark-writhing mass of moth wings waiting to spirit her away into outer space. And as dislocated finger connects with keratinous wing, my twin sister smiles.

My own hand—the one that weeks ago wielded the hammer and iron nails—tingles. It remembers reaching for my twin, and her drawing back from me even before the angels arrived. How she would look at me with an expression tight-roping between pity and disgust. As if I was another warden—another burden—like Mother had become after our father’s death. A day before the angels’ arrival, I had left a dissected moth wing as a gift under her pillow. She called me sick. Said: we aren’t children anymore. Said: you need to grow the hell up.

And yet, she became the chosen child. Flying, elated, ready to dedicate her life to a higher cause.

As I look up at the endless sky, I am leaden and heavy.

Rooted to the ground as if by iron nails driven through my feet.