The first thing I fell in love with, other than my family, was the fish in tank two.

My grandmother, a programmer for the Seasonal Conditions Department or SCD, held my hand as she led me off the stone path and away from the mossy green pond. We stepped up to an oak tree that’s limbs touched our digital sky.

“Feel this.” My grandmother placed my hand against the trunk.

The bark was slippery and hard, plastic. Artificial.

My grandmother’s smile showed off the ancient lines around her eyes. “It’s a door, little lamb,” she explained, stepping to the side of the trunk. She touched the surface and I heard a soft click.

Seamless bark opened. I jumped back and giggled. Electric bulbs flickered on, filling the dark hole with light.

“Where are we going?” I asked, following her down the stairs. I didn’t want to go, not at first.

“To show you the fish. You want to see them, don’t you?”

The red robes of my grandmother’s station, a comfortable reminder of her importance, whispered over her steps. She took my hand as a door slid open at the end of the stairs. The hallway lacked trees and sky, and the air smelled sanitized, like a medical floor. We weren’t alone. Adults in important robes of red, blue, and green walked the silver and gray hallway. Translucent holos, like those I played learning games on, hovered in front of their faces.

The hallway curved. Circular windows dotted one side of the wall, providing a view of hundreds and thousands of twinkling stars.

“It’s daytime,” I said, astonished.

“Yes, but we’re in space. Haven’t you learned that yet?”

I tried to understand what she meant. Space was empty air and space was outside, filled with darkness and stars.

The tank on the other side of the hallway shimmered under the slanted light from above. Hidden in cloudy aquamarine, dayglow flutters of fluorescents flickered, like starlight. I pressed my hand against the Plexiglas and they moved, danced. Some blinked to an inaudible rhythm and some pulsed.

“What are they?” I whispered.

“Fish,” she answered in a matter-of-fact way.

“Cal, has your mother explained death?”

I shook my head, unable to look away.

My grandmother leaned down to my height. I examined the fine lines that creased her neck. “Before we die, we are put in a tank, not this tank, but a smaller one. The fish take us, our memories, what we’ve learned and live on until someone eats them. Or they die, consumed by the computers.”

“How come?”

“So that nothing is ever lost, lamb.” She then pulled me into her arms. “I’ll pulse my light for you, forever.”

I closed my eyes, breathing in the scent of cooked sugar and earthy dirt. It was the smell of home, the smell of comfort, and love.

§

Everyone dies at sixty-five. If a soul lives longer their memories risk corruption and are rendered unusable.

History says we lived for much longer until a coming-of-age rite where a boy once ate a bad fish.

The boy was placed in maintenance, on a heating unit. His mistakes caused five deaths and an explosion that fractured society for the next decade. His evaluation proved he had confused the past with the present, due to eroded memories.

The next time I saw the fish was my grandmother’s sixty-fifth birthday. Her funeral took place in the glass dome, beside the park. Crowds filled the stands with our family, co-workers in her unit, and old friends. Their heads bowed as they clasped my grandmother’s hand. They called her brave as tears fell down their cheeks.

I’ve heard stories of other grandparents running away from the tank, of being dragged back to the platform, but not my grandmother. She stood tall and erect, calm in her red robes. Music started to play, one of her favorite songs.

Mother gripped my hand. Tears glistened on her cheeks like the stars outside the ship.

Grandmother swayed against the guardrail. Her eyes closed, her head tilted back, and her lips spread up in a smile. The song was old, slow, with lyrics that I couldn’t make out. The beat picked up with crashing cymbals and a woman’s deep soprano, pouring out one long note of lost romance.

The pressure of my mother’s grip increased as the song came to an end. I squeaked in protest, shaking my hand out of hers.

The people in the stands murmured as my grandmother stepped away from the tank. And I, like the rest of the gathering, wondered if she might run.

She picked up something too small to see and her voice projected through speakers. “My friends, thank you for seeing me off. It would be harder without you. I’ve been blessed in life.” She paused as if her words had failed her. “I look forward to joining the new generation. Until we meet again.”

As she let the tiny microphone drop from her hands she winked at me.

My mother moaned and I tried not to smile.

Grandmother walked back down the dock, removing the band that held back her thick mane of gray hair. It wound down in one swift fall. She then unclasped her red robe, letting it tumble down to her feet. She stood before us naked, glorious, and unashamed.

I loved her.

There’s nothing so beautiful as that moment of acceptance and surrender. She dove into the tank, graceful and quick. Her form hardly left a ripple on the water’s surface. She was obscured until a bright cloud of red spread across the top. It reminded me of her robes, her importance.

Hair, skin, and pieces of her floated to the top. Squirming little bodies started to glow in the clouded water, devouring her.

My mother’s cries grew into shrieks as if it was her flesh they’d torn apart.

Little fish flickered pink, flashing and pulsing.

Beautiful.

§

When the time came to eat my own fish, the ceremony took place in the same glass dome my grandmother had died in. The early morning projection of the sun slipped through the leaves of elm and oak, casting warm yellow rays through the glass. The fluorescent fish shimmered like diamonds under a light, flashing rhythmically, as if in anticipation of being caught. Neon green, hot pink, fuchsia, every color a bright light.

Two families sat in the dome’s stands.

A girl, born two hours before me went first. Her family consisted of an older couple, who sat hand-in-hand. In front of them sat a woman with long curly hair, like the girl’s. She held onto the back of a little boy’s shirt. His hair was just as curly, a shade of dark brown instead of the inky black of his mother’s. On the other side of the woman was a man with graying temples. He wore the suit of a watcher, those who kept the peace.

Unlike funeral rites, only family came to the fish consuming.

“No one wants to see teenagers choke down raw fish when they could watch the elderly be dragged to the end of the pool and pushed in,” my mom had said. As if it wasn’t a privilege to be passed down to the next generation. Her blasphemy could see her arrested if she wasn’t careful.

A man in royal blue robes, a “Keeper of Memory,” placed a net in the girl’s hand. She lifted her head, eyeing her parents in the stands. Her plump bottom lip trembled. Her curls bobbed up and down in time to the sound of her feet on the hard-plastic ground.

The tank gurgled as air bubbles rose to the surface. She dipped the net into the tank, her hand shaking like a tree limb in the park. The net dove deep into the tank and she drew in a sharp breath. She pitched forward, her feet wobbling at the end of the dock.

I wondered what would happen if she fell in. Would her blood blossom up, turning the water from blue-green to a red cloud?

Her hand shot up with the net, a wiggling fish pulsing with purple light caught in the mesh.

The Keeper removed the fish from the net and with practiced ease he slit the bottom of the fish open. Blood trickled out and landed at his feet as he scooped out the glistening entrails and dropped them into the water. Glowing fish broke the surface of the water, devouring the insides of their doomed sibling.

The girl was handed the fish. It was expected that she would eat as much as she could stomach. Her plump lips thinned and she grew pale. She bit into the side of the fish, choking and sputtering on the raw meat. Iridescent scales clung to the sides of her mouth and cheeks.

The Keeper offered her water before she could heave the fishy morsels up. She coughed into it, drinking her fill, before she took another bite. Her lips turned red with the fish’s blood, as she swallowed, choking it down.

My stomach turned, disgusted by her dishonor. Each bite gave her a piece of our history. Each bite held her future.

My Gran’s hands and voice had not trembled as she dove into the future.

I set my sights on the yellow and white ones. Council members wore robes of white. Yellow was for the engineers. I didn’t know if the color of the fish bore any real significance, but I was willing to hope.

Another Keeper helped the girl off the platform, offering her a cloth napkin.

“Can we go home now, Mommy?” asked the little boy in the stands.

“Cal,” my mother cried. Tears slid down her cheeks as they had for my grandmother.

“Don’t cry,” I told her as the Keeper handed me the net.

My palm was sweaty on the handle. I gripped it tighter and climbed onto the dock. Fluorescent dots twinkled under my feet, like a sea of stars. My mouth watered in anticipation. They’d taste like power and promise, each and every one.

I’ve never understood how memories go from a fluorescent glow and translate into static thoughts and information. It’s been explained through enzymes in the stomach and digestive tract, to blood cells and how our bodies absorb vitamins. The fish absorb calcium when they devour us, along with memories, causing the glow. It’s called Photoprotein. The glow lets us know it’s working. Our people broke down the steps and engineered the fish to need us, and in turn, we needed them. It’s a giant circle that’s traced back into the computer, keeping our existence regulated, making sure nothing is ever wasted.

There was other edible marine life, but none that could be genetically modified to contain our souls.

The Keeper muttered directions to me, but I didn’t listen. I leaned down and waited for the flicker of a yellow or white one. To my right I saw it. I dipped the net down, scooping colors in as if I’d done it hundreds of times.

Three little bodies wriggled in my net, splashing, and tossing. A purple one jumped out, its body twisted in the air, flinging tiny droplets of water across my face.

The Keeper laughed beside me and took the net.

“Blue or yellow? It’s rare to have a choice,” he said.

“Yellow,” I answered.

He tossed the blue back in with a plop. The small yellow one wiggled in his grip. The Keeper removed a knife from his robes and the digital sunlight cast reflections off its metallic surface. He carved out the innards of the fish’s belly, and I held in a protest.

I wanted it whole.

He handed me the fish and I sucked out its eyes, popping them between my teeth as if they were a rare delicacy. The gelatinous mixture was both sweet and salty. I crunched on the rubbery insides, below the gills. It tasted like salt and undercooked meat. Blood trickled down the sides of my mouth as I bit into the blood vessel along the backbone. I licked the sides of my mouth and ran my fingers under the sharp bones for the tender meat that melted on my tongue.

The Keeper’s hands gathered in front of him like a proud father, his eyes ablaze with false sunlight.

My mother gasped from the stands.

The girl who had eaten her fish before stood at the exit, watching. Her gaze held mine as I stripped the last fibers of meat from the bones and savored the moment they slid down my gullet.

§

The first real memory that surfaced happened in a dream. In the dream I worked at my terminal: code, code, and more code. Davey came over with his sheet of ones and zeros. His breath smelled like decay, and all I wanted to do was go home and have a giant glass of wine.

I glanced back at the tiny zeros and ones and tried to see what he pointed at and then realized he wasn’t looking at the sheet. He was looking at my tits.

“Christ, Davey!” I snatched the paper out of his hand and he was gone.

He was gone and I wasn’t at work.

I stood next to a chubby-cheeked boy with black hair and blacker eyes. He pointed out to sea. A ship sailed over water that reflected the blanket of tiny stars above. I handed the paper to the little boy, who laughed and said, “We’ll sail a new ocean. You’ll see, Calvin.”

“Calvin, sweetheart?”

I opened my eyes to mother’s hand on my shoulder, and her face, tearless for once, hovered over me. She sat down on the edge of my bed when I gripped the soft foam blanket tighter to my chest. I wanted to press my hand against my chest, to make sure I wasn’t the woman I dreamed.

“Did you have one of the dreams, already?” Mom asked. She smelled like strawberries and nail polish.

I cleared my throat and thought of the sea, which wasn’t a sea at all, but space that expanded infinitely outside of our ship. I’d known those things but not how to read a galactic map.

The little boy in my dream, his name was Puash, a child prodigy and scientist. He’d recorded maps, hundreds of maps.

He wasn’t the only memory. The one before him, a borderline alcoholic, Crystal, was an old-world coder. She was the oldest memory the fish had given me. She’d lived half of her life on Earth, in the Before.

I bobbed my head up and down. “The Before,” I said to my mother as she gripped my hand.

“I have one of those,” Mother said.

She used to work on the medical floor, but she hadn’t worked since my father had fallen ill. He received a grave diagnosis and was given to the fish shortly after.

I was too young to remember.

“I’m not supposed to talk about it,” I said.

She didn’t nod her head or tell me it was okay. Instead, she let go of my hand and straightened the lampshade. “Just remember, they’re not us. Just memories.”

I closed my eyes and imagined the wink my grandmother gave me, right before she dove in.

The fish held the doors to the past and our final dive into the unknown.

§

When I submitted my placement test, I was named an assistant Keeper of Memory.

My robes were aquamarine.

A Keeper of Memory’s duties were to take care of the conveyor of memories, the fish. My memories were full of coding, star maps, and maintenance level work, but the test singled me out for blue robes. I cleaned the tanks and monitored the proteins in the water. Senior members, starting at age forty-five, administered placement tests and prepared the ceremonies. Three weeks, after two coming-of-age rites and cleaning out more tanks than I could count, I took my second fish.

The impulse came in the evening as I watched over one of the tanks where I believed my grandmother’s fish throbbed neon pink. I’d dimmed the lights so that the water shone silver and black in the low light. Tiny lights sparkled in the depths and I connected the dots creating ever-shifting maps to far away star systems.

I took up a net and stepped toward the feeding plank.

The tank was larger and deeper than the pool used for coming-of-age rites and memory acquisition. It held the bulk of the fish old enough and large enough for human consumption.

I scooped a fluorescent pink fish into my net. It squirmed and wiggled, protesting the fate of my teeth.

I thought of the story of the young man who’d eaten corrupted data, and then I saw my grandmother—naked as the day she was born.

She’d promised to see us again.

The fish squirmed in my grip. I bit into its gills before I lost my grip. The spiny ray above the dorsal fin cut into my palm. Our blood mixed and slid down my hands as slippery scales came off in my mouth.

I threw the innards into the tank and munched on the soft meat along tiny bones. I pierced the large blood vessel and sucked at it until my head spun. I sucked at the eyes last, savoring the delicate flavor that burst across my tongue.

I’d washed, changed, and sat down in the locker room, half regretting what I’d done. And then memories ripped through me.

On a school trip we’d explored a menagerie of Earth’s animals locked away in enclosures. Great hunting cats lounged under warming lamps, licking their giant claws. I’d wanted to see those claws tearing into the flesh of their prey.

The memories tore through me like giant claws. Great talons gouging my skull, filling it with flashes of pain and memories. Attaching electrodes and sending pulses into my temples would’ve been kinder. I ground my teeth together as I became more.

I saw an old man in a hospital bed—the oldest man I’d ever seen. Machines beeped, standing alongside tubes that connected to catheters. The old man gripped my hand and squeezed. “You can’t let them go through with this. You can’t let them stick me in that tank. You know it isn’t right!”

He was too old to go in a tank, but this was before the rule of sixty-five.

“They’ll sedate you first. You wanted this,” I told him, angry that he was backing out. He’d die either way, but this way some of him would stay behind.

I wasn’t scared of death, and I tried to remind myself that it was easier to think that with so many good years left.

Only I didn’t think it. She did.

“Dammit, Layla! Would you just listen?” the old man asked.

The words were in French, from the Before.

I blinked, and I was Cal again.

§

I scrubbed the tank with a long brush and thought of Layla. Her memories were sharper than the others.

I watched the tank holo apps as I worked.

One of the app’s readings spiked—a drop in the water temperature from tank three. The tank housed what we called, “The Hungry Fish.” Their translucent bodies were pale white, the color of steam. They wouldn’t hold the memories of devoured souls until they reached maturity.

I logged in and sent the readout to the tank system administrator and my manager. I headed down the spiral staircase to the tank’s environmental control unit. Fish occasionally appeared beside the unit from within, their ghostly visage dancing in the dark water.

A yellow notification flashed in the corner of my eye. I opened it and the administrator said, “Try manually shutting it down and then start it back up. If that doesn’t fix the problem, let me know.”

Why I hadn’t made administrator yet was a mystery, not when their job revolved around common sense.

I shut the unit down and waited for the humming to die.

Green and blue fish in the tank behind me huddled together in threes and fours.

I turned back on the unit and waited for the hum to stabilize.

I eyed the fish that followed me. My mouth watered as I imagined sucking their eyes out.

The fish I took was electric green, brighter than our genetically-enhanced trees. I bit into it as the temperature in tank three returned to normal.

§

“Ugh. Why are we still in bed?” asked Layla, the French biologist.

She was me. I was her, and there was no line in-between, not after the last fish.

“Just a few more minutes,” Puash, the boy, said as I rolled over.

I was a child genius. Who did I need to get up for?

I knew the voices weren’t real. Only they were real, years ago they had lives, and now I made them real again. This wasn’t supposed to be how souls lived on.

It could be a side effect. Too many souls trapped in my brain tissue. Layla reminded me that wasn’t how the fish worked. Memories weren’t souls. Souls were for the religious and spiritual. But she wasn’t certain about anything.

The boy flickered back and forth. He thought work was boring, and he hated my apartment.

The strongest persona, stronger than Layla, called herself Repair. Her memories were sharp wrong things that drove nails into the sides of my head as if she were fighting me.

In the ship year 204, she’d been the captain’s wife, until she led a rebellion against the council and her captain.

She should have been fed to the computer, not the fish.

Her rebellion ended in the park by the same tree that my grandmother had led me into. A shootout involving stun grenades and tranquilizer guns haunted my dreams. I could feel the beat of her heart and the sweat on her forehead.

“We have to split up and go around,” she’d said to her meager group of ten.

Men and women bobbed their heads and their stolen weapons flashed silver under an artificial sunset. She knew they were all done for, but if she could find a place to hide the chip …

The chip, hidden in a necklace shaped as Thor’s hammer, Mjölnir, rested against her chest. Her squad fanned out, drawing fire long enough to hide the chip in a stone beside the doorway. She opened the tree door with a soft click before pain shot through her back. The dart stung, wrapping her body in cold fear as she fell and fell.

“We have to see if the chip is still there. We can still end this,” Repair urged me.

“End what?” I demanded, standing under my living unit’s showerhead.

“The fish.” It wasn’t Repair that said it, but Layla.

I laughed at them and thought of my fluorescent stars, my tiny sweet bodies. As if I’d ever destroy them.

And then I wasn’t in the shower anymore. I was a tied up ten-year-old boy. His arms were bound above his head. The crane lifted Puash (me) above the ground until my feet dangled in empty air. My shoulders throbbed. The crane moved over a pool where little ghost bodies swam in inky black water.

Momma would come. Momma wouldn’t let this happen to me.

Where was she?

The crane started to lower and his feet (my feet) came closer and closer to the water below.

“Dammit. Stop!” I screamed at all of them, but others were giving their death stories.

Repair didn’t know hers, nor did Layla, but there were others. A man who’d never see his daughters grow or see his grandchildren. Another woman who’d just found love, real love. The kind that filled her heart and made her knees weak. A week later she turned sixty-five. Her lover promised her that he’d watch her last moments, and she promised him that his face would be the last thing she’d ever see, but that hadn’t happened. It’d been the whip-thin man in blue robes. He pushed her off the dock, his lips pulled back in a cruel smile.

“How many years before it’s your mother?” Layla and Repair asked together, in two different languages.

A message shut them all up. A message in red. It wasn’t from my contact list, but whoever had sent it was important enough to escape my blocker. It was an assistant member of the council asking to meet.

Another message, this one in yellow, from my manager. He wanted to let me know I had the day off at the formal request of the council.

“They’re going to kill you, too. Get the chip before that happens,” said Repair.

“What’s on the chip?”

Silence answered, but her frustration buried itself in my skin and tingled in my fingertips.

Either the council wanted the chip and knew what voices warred in my head or I was going to get dropped in the tank. All life goes to the fish and back into humanity. And if not humanity then to the computer. Nothing ever really dies, not in space.

“That’s a lie!” the boy screamed.

My fist struck the counter. My knuckles throbbed. I hadn’t hit the counter. It was the little boy who could chart the universe. The rebels in my head drowned me out.

Repair hit the button to open my door.

§

Repair took over my body as my vision blurred and narrowed. My feet ran down the steel stairs, headed toward the shuttle.

I was her.

White walls blurred into gray slants that dimmed to darker shadows.

“This is death for us,” whispered one of the others.

“If you consume us, then you are us. How much better would it be if you could have kept your grandmother a while longer?” asked Layla.

“What is Repair doing?” I asked.

“What she has to,” said the man who never got to see his little girls grow up.

Every single person in my head agreed. Did my grandmother feel this way? Was she floating in someone’s head telling them that consuming her was wrong?

“The killing is wrong,” Layla snapped. “Why don’t you get it? The government takes life and uploads it into children. Why, Cal? Because it’s easier than teaching them how to do their jobs?”

“But no one really dies and nothing is ever really lost,” I argued. We’re gods conserving the heavens inside of us.

The voices stopped and I could see again. I stood under the artificial tree in the park my grandmother took me to as a child. The sky was soft blue with puffy clouds that lazily crossed the sun. A small stream bubbled up from the rocks and ran along the trail.

“Well?” asked a woman behind me, only she wasn’t a woman.

She, like me, was seventeen cycles. The girl who had eaten a fish before me at the coming-of-age rite. Her robes were pressed, white, and embroidered silver and gold along the hem. The robes identified her as an assistant to the council.

A message popped up in yellow. My presence was demanded before council chambers. A clerk, not an assistant, had sent it.

Behind the girl stood her father.

“You asked me here,” I said, surprised. “Not the council.”

“I’ll ask you one more time, or you can deal with my father. Where is the chip?”

Her father held something black that pointed at me, a stunner.

“If they knew what I did, they’ll know what you’re about to do,” I warned her, backing up toward the tree.

“No. We made sure of that. And we know the repair virus has infected you,” she said.

My back touched the tree door. Its solid structure was the only thing that kept me from the stairs. I’d rather be replanted in someone’s skull than at the mercy of whatever this girl was part of.

“Repair virus?” I asked.

She smirked, her lips drawing back to expose teeth as white as her robe. “You’ve met her already.”

My hand pressed the tree door. It clicked as her meaning became clear. Repair was never the wife of a captain. She was a virus and I was infected.

“The chip, now,” she said.

The chip was a step away from me, if it was still hidden in the rock, but if the memory of Repair was fake then why would the chip be there at all?

I threw the door open and rushed down the same stairs my grandmother led me down once.

The girl’s father chased me. His boots pounded the stairs matching my heartbeat.

“I knew your grandmother, Cal,” he called.

No. My grandmother had seen her fate in blue waters. She’d dove in, head first without blinking.

“She helped us engineer the virus, using her DNA. That chip is the next step, the test that means you’re ready.”

A hundred fish had pulsed in a dark tank, like gemstones, waiting to be worn. Waiting to be reborn. My grandmother had leaned down beside me, her robes whispering against the floor.

So that nothing is ever lost, she’d said.

Angry heat rose inside my chest like a wave crashing. I whipped around, facing my attacker. “Liar,” I accused, like a curse, spraying spittle. “She’d never help you.”

The stun rod in the watcher’s hands didn’t look the same. The tip was red, like the color of water after the fish ate.

“It’s a shame, Cal. You’re turning her sacrifice into nothing.”

My grandmother smiled at her end.

I forced my lips up and eyed him. He laughed, as if I was some sort of joke, and then the dark wand jabbed my chest.

“Did you get him?” asked the girl, through a holo app.

“Yes. He’s gone. We’ll have to wait till the next program goes active.”

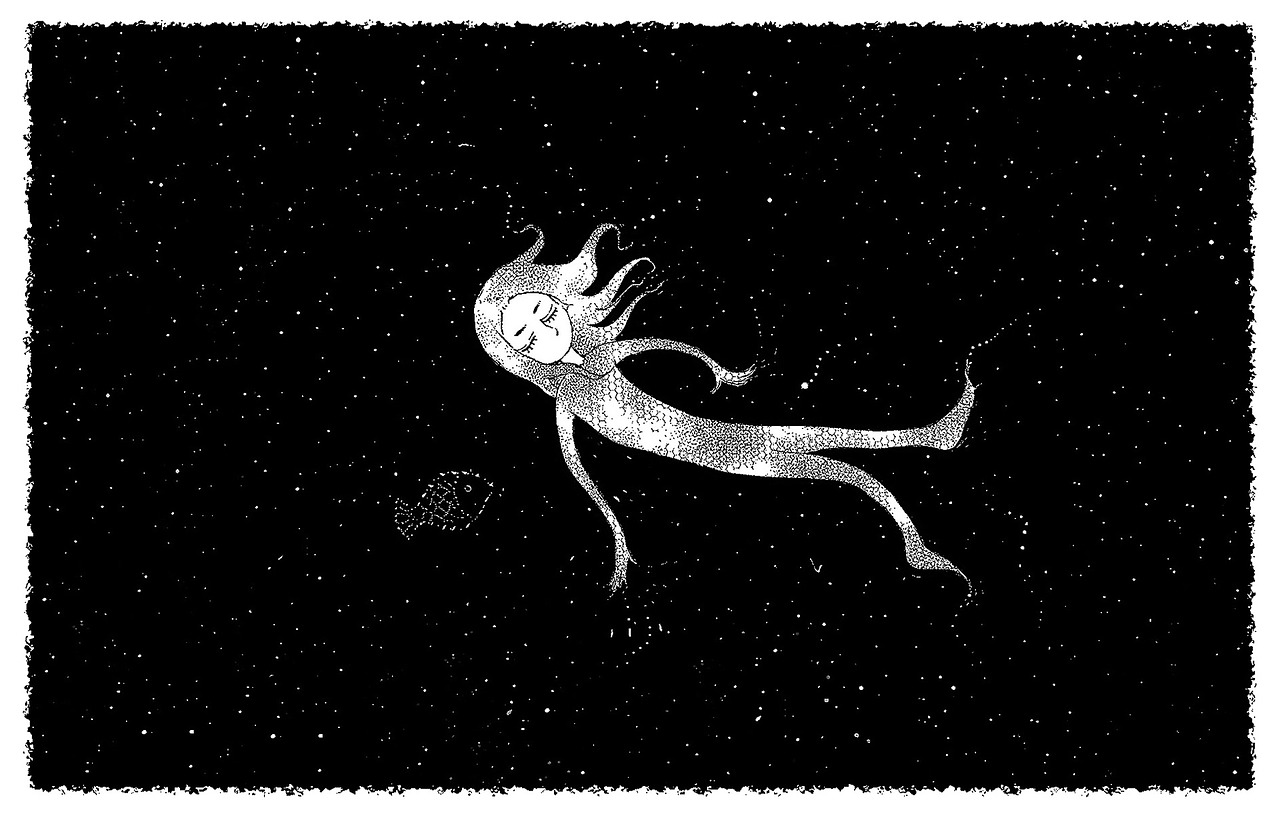

Warmth gave way to heat as if flames ate my insides. Orange and then yellow circles crowded my vision. In their bright centers I found darkness. It reached out and consumed everything. The fire inside of my skin left my arms numb, followed by my legs. I could hear a high pitch whine.

I’ll pulse my light for you, forever, my grandmother had said. I’d thought she knew how glorious the souls were, floating as if angels in a sky. I reached out, with arms made of thoughts. I tried to call out to her but I had no mouth, no arms. I was nothing.

As life turned its back on me, I wanted more time. Seventeen wasn’t enough, neither was sixty-five.

“We are here,” said the boy. Together we hummed a lullaby my grandmother had sung to me. Before we faded, I saw a flicker of hot-pink light.