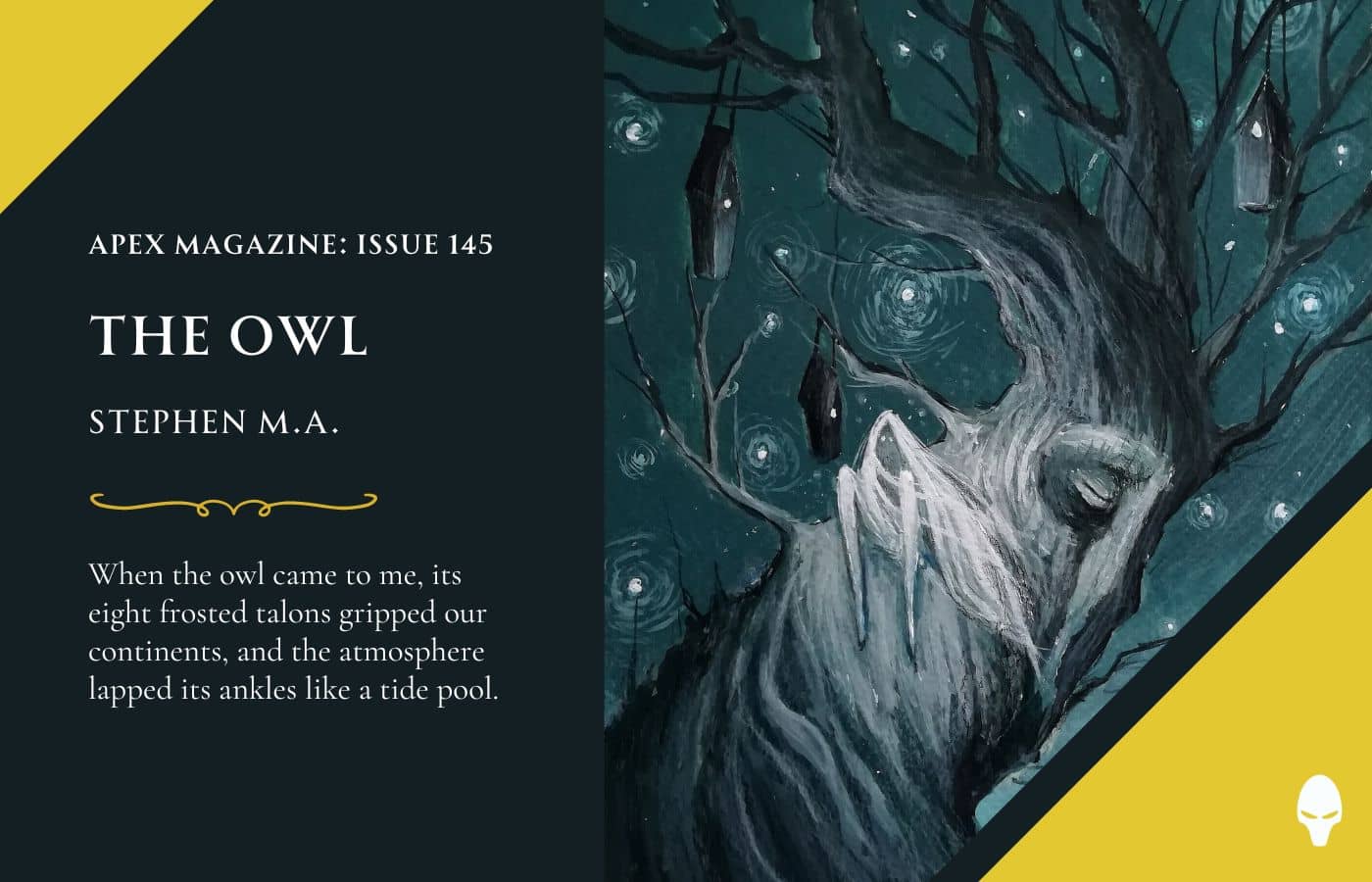

When the owl came to me, its eight frosted talons gripped our continents, and the atmosphere lapped its ankles like a tide pool. When it lowered its head from orbit, the coma of its face filled the sky above my front porch.

From the day its massive bulk had been spotted rounding Neptune, I’d known matters would come to this, and so they had, here at the final summer solstice.

The owl’s pooled green eyes, fixed on mine, blinked with the weight of countless gravities. The susurration of those moving lids fell like rain poured over the splintered Montana home where I had lived for all but two of my eighty-three years. My very ears welcomed such caress, at last, after so much time spent ringing with silent lies.

When the owl spoke, its voice filled my bones, and its words made syrup of the air in their wake. It said, “Child, shall I save your peoples? Some ask this of me, even now, when my task is made inevitable by their own malefaction.”

I rocked among creaking teak for a time, and then, from this chair, replied simply.

“Absolutely not.”

The owl nodded then, and a great gale issued from such gesture, washed in hissing ripples over fields of verdant barley which had been planted only weeks ago, by folks whose corpses now lay rotting atop this very same soil.

“Tell me why,” it said. Then it blinked once more, slowly, and with expectation.

I nodded in kind, and began.

When we were young, we carved homes into thickets of huckleberry.

We made acrid wine of the fruit, and stored it in Mountain Dew bottles, nestled among the roots in a shrubby pantry, which had been hacked into blistered relief with broken yard shears and other rust-eaten tools thrown out by parents.

We played mommy and daddy and baby and teenager, and daddy and daddy and mommy and baby, and mommy and daddy and grandpa and uncle. We made dinner of bitterroot and clover stems, and said our prayers, and lay down on loamy beds to hold hands and watch stars winking through the bramble overhead.

We reveled when our own moms and dads neglected the spring brush burn for several years running, and expanded our dominion into thickening thickets, until they made a sprawling maze connecting our four homes to each other.

We smoked our first Camels in that maze, stolen from the IGA, then prayed for forgiveness, and buried the soft packs deep beneath the beaten dirt threshold of our living room clearing. When the Bulls made the playoffs, and the parents whooped around backyard firepits slugging cans of Coors, we exhumed the cigs, and tried to blow celebratory smoke hoops in the air, to float above the huckleberries.

A stray ember caught the droughty undergrowth, and nearly burned the entire street to the ground. Nothing remained of our leafen kingdom, save the implements we’d used to create it.

After the fire trucks left, the boy whose parents had discarded those tools began shaking when they were discovered among the ashes, and his parents whipped him with a rodeo belt until he fled screaming into the hay fields. Such reprimand left weeping wounds as testimony, purple as the berries, which we salved in pale yellow, with yarrow gathered from empty irrigation ditches. Then we sent the boy back home, with a gleaming handful of Jolly Ranchers hidden inside one sock, because we couldn’t convince our own families to take him in for the night.

“We ain’t sticking our nose in nobody’s goddamn business. Pray for him if you want, but shut the hell up about it now, hear?”

The next day, he shared the Jolly Ranchers with us at school, but would not say why he hadn’t eaten them himself. He wore an overlarge Dallas Cowboys sweater, even on the playground, where a bronze sun baked the golden sawdust into shimmering waves.

We let him listen to Paula on the Walkman all day long, and nobody complained about losing their turn, not even the boy who lived next to me, who’d received it for Christmas.

Later that night, we listened to the crickets and shared a bag of Skittles in the ashes of our huckleberry kitchen, then swore on a kiss that we’d never be cruel losers to our kids.

When we were young, we’d just returned from driving around the gravel back roads in his rattling Taurus, listening to Dookie for the millionth time. We’d been saying our goodbyes when he suddenly stopped on a dime, pulled up next to the thickets.

Even at the end of winter, the old growth was out of control again, piled into a solid wall next to the asphalt. But he got out without a word, then moved with some unknown instinct, stomping a beeline toward a particularly tall patch, tangled deep in bramble claws that pulled his windbreaker taut across his chest.

He found her surrounded by dormant huckleberries, curled in a bower, covered in scratches just like his. The bruise on her cheek was from the preacher man, she eventually admitted to us, when she’d tried to run out of his office.

It was her own fault, she said, for staying too long after timbrel practice. She screamed at us when we tried to say otherwise.

We begged her to tell her mom and dad, then begged her parents to believe her accusations, then begged our own to disclaim theirs after they tried to blame us instead, and cast us out of her house, bellowing into the night as we sprinted down the street, a clatter of untied Airwalks, hearts pounding in terrified indignation while the rifle blasts rang out overhead.

“Don’t you fuckin’ dare bear false witness in my home, boy! Tell your fuckin’ mom her piece’a shit ain’t welcome here no more when he can’t even keep it in his GODdamn pants! All three’a you fuckin’ monsters! Tellin’ lies on a MAN OF GOD!” BOOM! “Don’t you fuckin’ EVER come back!” BOOM!

We hid in the thickets for hours, until he finally managed to stifle his anguished moans and wipe his face dry. He wanted to murder the preacher man, right then. Probably would’ve took off and actually tried, if we hadn’t been able to drag him inside.

Our parents ordered us to apologize to hers, then grounded us for a month when we refused.

Her parents sought counsel from the very same preacher man, who recommended ongoing scripture study at the church, in private, to help her learn repentance, and to live a life of testimony and witness.

She stopped driving with us to school, then began ignoring us in class, and one day she never showed up again, even when it came time for our junior prom. She hadn’t been able to shut up about that prom all winter. She’d been invited to the planning committee. The theme was Owls in Flight, and the student council had transformed the elementary gym into crepe paper moonscapes, with glittering stars hanging from the hoops.

She used to love the moon.

He waited for her all night, standing near the stop sign, bouquet of flowers in hand. He kept out of the streetlight’s spill, and flinched at the sound of his kitchen door slamming open in the distance.

All the windows in her house were dark, the way they’d been for days on end, even though the Suburban never moved. We didn’t know if the whole family was really gone, or if they were just sitting there in the blackness, staring out across the fields.

Me and the boy next door cupped our palms to hide the glowing cherry while passing cigs back and forth. We wouldn’t be caught dead at prom ourselves, and said so a few times, just to keep things light. He only grunted in reply.

It was too cold to be standing out there, especially after midnight came and went, but we never dreamed of asking him to go in. Instead, we shared the old Walkman, one piece of broken headphone for each of us, while holding hands inside our coat sleeves, and feeling each other up whenever he was facing the other way, out of respect.

He spent most of the night pacing around the stop sign, and touching the scars under his rented tuxedo, where her own hands had once spread yarrow on his skin.

When we were young, she suddenly turned up at home with her parents, the week after senior year began.

He’d risked his life to sneak beneath her bedroom window, just to see her face one more time, and to welcome her back to the street. She’d promised to meet us after church, but only if we waited respectfully outside.

That was just before Brokaw interrupted Days one afternoon, to calmly announce the owl’s discovery.

They all appeared in a group on the chapel stoop at precisely 11:46 a.m., then paused to chat while the preacher man said goodbye to his flock, who were dutifully shepherding themselves to the dusty parking lot filled with rusty pickups and sun-bleached Chevy wagons.

The three of us loitered on the lawn, waiting silently. But I couldn’t help noticing that the preacher man tried to avoid looking at her, and when this was unavoidable, it was done with a glare.

“Do they all know where she was this whole time?” I finally asked him.

“Duh,” he muttered. His voice was tight, arms crossed, fingernails digging into fisted palms.

“Is that why he looks like he hates her guts?” I narrowed my eyes, watching the preacher man close.

He shook his head sharply. “Dumbass, it ain’t because of that. It’s because she didn’t keep it.”

“Keep what?” I said, loud and clueless, like a fucking dumbass. Her dad glanced my way from the stoop.

He swiftly punched me in the ribs and hissed back, “The baby, ese, goddamn.”

Oh shit.

I clutched my side and stared at her in disbelief, amazed that it was still possible to become a complete stranger, even after all these years.

I beheld her parents with new disgust, skin prickling at the sight of them standing there, calmly chatting with the preacher man, while she waited silently at their shoulder, face placid and resolute.

I felt a stab of guilt at the disloyalty in my ignorance, but kept the pained gasp inside my lungs, so my bruised ribs would hurt all the more, because I deserved it.

I deserved it.

But not as much as her mom and dad did.

I tried to tell her so once, just before graduation, but she brushed me off with a flat burst of laughter. By then she was too far gone to bother litigating yesterday, never mind months ago. Too tired of resisting. Too tired of hoping for more. Anyway, apologies were meaningless in the face of the Great Redeemer. So was guilt. And blame. And responsibility.

She’d settled on her survival strategy, and it required only one thing of her, one task to complete, one rule to follow.

Be not of this world, at any cost.

Now, like the rest of them, she preferred to reject the crushing burden of causality, to give it away, to send it back to the universe, and to leave all things unto Him, instead.

The universe, in reply, sent us the owl.

When we were young, they’d been officially dating by Christmas, and his parents lost their minds about it, nearly as much as hers. Nobody ever admitted to knowing about the preacher man, but she was clearly tagged as damaged goods among the elders.

The worst part was that she didn’t disagree. She’d used those exact words herself, more than once, even though he begged her to stop.

We were both intensely protective of their relationship, but also grateful that it was drawing so much attention, making our own easier to ignore. We were determined to stay hidden beneath the radar, hands held under desks, whispered plans to hitch a ride to Missoula’s second-ever Pride party that summer. But we still couldn’t help ourselves beating the shit out of some sophomores who’d sneeringly referred to her as the church bike outside a basketball game.

His lip was bleeding afterward, and I’d reflexively held his face and said, “You alright, baby?” And so we were not hidden anymore.

After graduation, all four of us rented the house beneath the water tower, right on the edge of town, where we planted a huckleberry bush in the garden, and barbecued every night with crumbly Western Family briquettes, and blew smoke rings at the mosquitoes dancing around the porch lights.

Both our moms and dads had stopped talking to us, but we didn’t care about the old homes anymore. We had our own now.

The owl had fallen out of headlines by then. Tentative plans to try and scare it off had been deemed too expensive. Anyway, the governments said it had no interest in us, and would leave our system when it was ready to move on, probably soon.

Probably soon.

But I was still seeing it every night in my dreams, bending down through the clouds to rip the roof off its rafters and peer into my eyes.

When we were young, we’d expected her to stop talking to her parents as much, or at least go to a different church. But instead he started going with her, every Sunday.

We interrogated him about sitting there, week after week, pretending to listen respectfully to the preacher man. Her parents had obviously forced her, but how could he stand it? How could he stand it for even an instant?

He assured us he wasn’t falling in deep, just fallen for her, and determined to live every part of her life, right alongside. He said he didn’t need to understand her decisions in order to love her, and we could only bring ourselves to agree, despite the seemingly inevitable cost to them both.

When my own parents died a year later on I-90, the firemen said they hadn’t even been wearing seatbelts.

He held me tightly while I wailed, then strapped my bed frame and mattress to the top of his Taurus and brought them back home for me, back to the street, to the empty house.

My house.

The three of them set up chairs for the wake in my backyard, then spent the night, one last sleepover listening to the crickets through open windows.

We’d talked about moving in together, just the two of us, but he said he preferred to stay with them under the water tower, closer to town, and further from his parents, who still lived next door. But one afternoon, several months later, they told me he’d left on the Greyhound, gone to live with a twink on the Clark Fork, having made them promise not to tell me for at least a week. They showed up in the Taurus the very same hour, with bison burgers and a twelve-pack for the backyard, and a burned CD filled with Tina and Whitney.

Their own parents still refused to bless their growing union, and it infuriated me. But one night I swallowed my anger, for their sake, and ushered the mothers and fathers close, to watch our home movies, and witness the nature of this inevitable unity. Coors would smooth the way.

Begrudgingly the parents obeyed, and stared silently while I explained, then hit Play on the two of them dancing in our yard beneath the tower, oblivious to being recorded, while LeAnn sang of love on the boombox.

But after all these years spent breathing the same air, it was me who watched the two of them with new eyes. I felt a pang at having been right there, holding the camcorder, and still having missed what was recorded here for posterity, as they circled together in the pixelated porch light, swaying under minor key.

He touched herself, as she had touched himself, and they had touched themselves in kind. They had both been built a quilt of holes, punched into their body at every place where a hole should not be, deliberately hollowing them out, until the wispy tendrils of their remaining girders could but collapse inward, making dense neutron stars at the center of their life, before sucking even the steaming ash into those gaping maws at their core.

What’s more, they both desired this consumption, in their own way, that it might assuage the endless guilt of forcing this town to behold such ongoing carnage any longer. Now they were spiraling in, trajectories set, twin event horizons blooming together, right in front of our eyes.

I wiped my face, voice thick as I turned to say, “Do you understand?” I was ready to forgive on their behalf, that they might find peace in the singularity, somewhere, and perhaps.

But the mothers and fathers had already gone.

When we were young, the first virus arrived just after she’d found out she was pregnant with their eldest. He insisted we take it seriously, to keep her safe. I needed no such convincing. But when the second virus came, and their son had given them their first granddaughter, the arrogance of survival had infected our world down to the bone, and suddenly nobody else could be convinced at all, no matter how I begged.

He hadn’t been pretending to listen to the preacher man for years. They’d both fallen in deep, just like the twin depressions worn into their family pew, side by side. We’d all stopped exchanging Christmas gifts after they insisted on giving me a new Bible every year, to replace the one I’d thrown out the previous. My last gift to them had been a sandwich bag filled with condoms.

When the new virus arrived, the preacher man, now stooped and withering, said come with joy, and pray for His shield, and so they went, spilling over the pews in their fervor.

The governments tried the same old trick again, tried to convince us it only took the old and weak, but I was forty-two when I said goodbye to the last of them, for the last time, and started coming home to a half-empty street, outside a half-empty town.

I hadn’t known I was saying goodbye. I hadn’t known I should have been marking the time.

I hadn’t known life could be so long.

They razed the huckleberry thickets at some point, when the dust bowls had really dug in deep down on the prairies.

Barley was what the seed banks sent, so barley is what they sowed. I watched it spring into life all around me, first hesitant, then quick and fierce, like a new love, before it settled in for the long summer, green stalks outside every window, waving languid and thick in sweltering April afternoons.

By then I was actually enjoying the heat, and regularly sat out front, so the sun might beat itself into my stiffened joints.

Given how isolated the countries had become, nobody could explain the strength and speed of the new bacteria, except that we were all riding overused corpses by then, with immune systems whose every secret had long since been laid bare to the enemy, worldwide.

Still, they insisted on celebrating the planting with the usual potlucks and festivals, “like a real community oughta,” and then one day they all lay down and let the whispering fields swallow them up.

Every last one.

I carefully placed a hand on each of the rocking chair’s arms, then inclined my head. “Thank you for listening.”

The owl’s head inclined in turn.

My eyes narrowed with curiosity. “If I’d been able to offer you a huckleberry for your journey, would it have spared us?”

“Perhaps.”

I felt my pulse racing. “Then I’m glad I cannot.”

The owl said, “Shall I at least sing of this world in my travels, child, that it might live among the stars? I could offer this, you know.”

“No,” I replied, voice shaking with adrenaline.

Then slowly, achingly, I stood from this chair for the final time.

I carefully spat on the ground, teeth bared. “For sake of the dead, I sincerely decline.”

“But why?” the owl said. Its face tilted in anticipation of my answer, and to say this was not a question, but a fail-safe.

I made arthritic fists, stuttered by pain, and thrust my whiskered chin high into the air, before embracing the final audacity with a voice so small it would not even echo off the owl’s face.

“For I am become vengeance,” I shouted into the sky, and immediately burst into furious tears.

The owl blinked at my words, then flexed its talons to crack this world in twain, before alighting back to the beyond, without another glance behind the long and icy tail of its own feathers.

At last.

The fires rose within crumbling soil, the barley began slipping away in all directions, and the atmosphere poured in waterfalls toward a glowing molten core.

As the porch dropped out from underneath me, I shut my cindering eyes, and smiled at the bird’s exceeding grace.