He was known by whites on both sides of the Atlantic as “the Indian Bonaparte,” “the Indian Wellington,” and even “the Indian King Arthur”—all sincere compliments from an Anglo perspective—even before his tragic battlefield death in 1813 ensured that his life and myth would remain inextricably bound together. Arguably no other single representative of Indigenous America has so consistently captured the imaginations of mainstream writers over the past two centuries. After popular eulogizing, fantasizing, and romanticizing became long-established trends, Tecumseh’s literary afterlife took a new turn.

The maddening “What if?” of Tecumseh’s story made him a natural subject to view through the lens of science fiction, and it was this genre that gave Tecumseh new (after)life as a symbol for Native America.

Who Was Tecumseh?

Tecumseh was a Shawnee leader who created a pan-tribal Native confederacy to oppose westward expansion by the United States in the early nineteenth century. The idea of a coalition didn’t begin with him. Tecumseh inherited a tradition of organized resistance from other great chiefs before him, such as the Ottowa leader Pontiac, the Mohawk leader Joseph Brant, and his fellow Shawnee leaders Blue Jacket and Captain Johnny. The more personally charismatic, politically adept, and militarily savvy Tecumseh, however, forged an alliance of Native peoples on an unprecedented scale; members of his confederacy spanned the North American continent from Spanish Florida to British Canada.

He gained fame as both an ambassador and unifying force for his people, and his military prowess was renowned. He exemplified cool and clever strategy in battle—knowing Tecumseh led the forces against him, the Brigadier General commanding Fort Detroit surrendered in sheer terror without firing a shot in 1812—paired with generosity and loyalty to his warriors and mercy and respect to his enemies. While he became a lasting symbol of Native American identity and resistance, he was a cultural purist, not a political separatist; he forged lasting partnerships with Anglo leaders, most significantly British Major-General Sir Isaac Brock, with whom he co-led forces against the United States during the War of 1812. Thanks to Tecumseh’s remarkable leadership of his pan-tribal Native army in alliance with the British during that conflict, he also became a Canadian national hero.

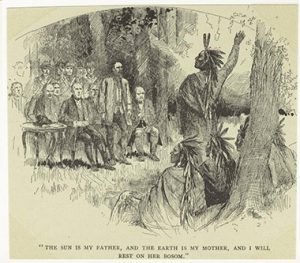

His primary U.S. military opponent, Governor of the Indiana Territory William Henry Harrison, described Tecumseh in 1811 in this way:

“The implicit obedience and respect which the followers of Tecumseh pay to him is really astonishing, and more than any other circumstance bespeaks him one of those uncommon geniuses which spring up occasionally to produce revolutions and overturn the established order of things. If it were not for the vicinity of the United States, he would, perhaps, be the founder of an empire that would rival in glory that of Mexico or Peru. No difficulties deter him … For four years he has been in constant motion. You see him today on the Wabash and in a short time you hear of him on the shores of Lake Erie or Michigan. Or on the banks of the Mississippi, and wherever he goes he makes an impression favorable to his purposes.”

So potent was Tecumseh in the popular consciousness that multiple U.S. soldiers lied and fought over the notoriety of being known as the one who had killed him on the battlefield, and William Henry Harrison rode the distinction of defeating Tecumseh all the way to the White House.

Of course, if you like your history on the more legendary side, you know that Harrison didn’t get the last laugh. He died in office, as did all of the U.S. presidents elected in years ending in “0” until Ronald Reagan, who came quite close when John Hinckley Jr. attempted to assassinate him. That’s seven dead presidents in a solid 136-year run for the so-called Curse of Tecumseh.

Tecumseh in Popular Literature

During Tecumseh’s life, many whites on both sides of the Atlantic were fascinated by him even as others feared him. After his death, his fame only grew. He became a romanticized hero as well as an admired symbol of principled leadership. His fall at the Battle of the Thames (also known as the Battle of Moraviantown) ended his story in 1813 with an extra dash of pathos. He died standing his ground, fighting shoulder to shoulder with his warriors, after his British allies turned and fled the battlefield, abandoning the Native Americans to slaughter. The Major General in command of British forces, Henry Procter, was later court martialed for this cowardly flight and betrayal of Tecumseh.

In 1818, Lieutenant Francis Hall, a British officer, published a poem in memory of a man he clearly revered. “To the Memory of Tecumseh” (as quoted in C.F. Klinck’s Fact and Fiction in Early Records) exemplifies many such tributes to the tragic chief: “Tecumseh has no grave, but eagles dipt/ Their rav’ning beaks, and drank his stout heart’s tide …”

Although Anglo culture found much to admire—and appropriate—in the chief’s story, Tecumseh was undeniably exotic and all the more mysterious and romantic because of this. In The Life of Tecumseh and of His Brother the Prophet (1841), Benjamin Drake quotes Judge James Hall on Tecumseh: “He was called the Napoleon of the west; and so far as that title was deserved by splendid genius, unwavering courage, untiring perseverance, boldness of conception and promptitude of action, it was fairly bestowed upon this accomplished savage.” Terms such as “genius,” “courage,” and “boldness” fit Tecumseh well, but he was not a Napoleon. The confederacy Tecumseh championed was not an empire in the making; it was an act of self-defense.

Canada’s celebrated first novelist, John Richardson, actually fought with Tecumseh at his final battle at Moraviantown before writing about the great chief. In 1828, Richardson penned a verse epic entitled Tecumseh: A Poem in Four Cantos, which presents a portrait of Tecumseh as a self-sacrificing republican hero who ultimately welcomed his own tragic demise. James Strange French’s 1836 novel, Elkswatawa; or, The Prophet of the West, draws parallels between Tecumseh and Hannibal, the strategist of antiquity often lauded as one of the greatest military commanders in human history.

Richard Emmon’s 1836 play Tecumseh; or, The Battle of the Thames, A National Drama underscores Tecumseh’s chivalric virtues and humane values—something of an irony, since it was commissioned to serve as campaign propaganda in support of then-Senator Richard Johnson, one of the men who claimed to have fatally shot Tecumseh during battle. William Galloway’s 1934 Old Chillicothe: Shawnee and Pioneer History distils earlier legends about Tecumseh, and its folklore remains the inspiration for a historical drama still performed today in Chillicothe, Ohio. Galloway both appropriates and assimilates his subject; Tecumseh falls in love with Rebecca Galloway, a white girl, who partially succeeds in Anglicizing him before he meets his final destiny. Galloway overtly compares Tecumseh to Hamlet in both his great promise and tragedy.

After the turn of the century, the tide of Tecumseh-related fiction continued unabated. For instance, German author Fritz Steuben published an eight-book series of novels about Tecumseh’s life between 1930 and 1939. Tecumseh and his brother the Prophet play key roles in Alan W. Eckert’s 1967 novel The Frontiersmen: A Narrative, the first in his six-volume Winning of America series; Tecumseh also takes the spotlight in Eckert’s 1975 Tecumseh! A Play and his 1992 fictionalized biography of the chief, A Sorrow in Our Heart. Furthermore, James Alexander Thom published his novel about Tecumseh, Panther in the Sky, in 1989, and in 1995, it was adapted into the TNT original film Tecumseh, The Last Warrior. Recent works such as Rosanne Bittner’s Into the Prairie: The Pioneers (2004) and L. C. Fiore’s The Last Great American Magic (2016) have brought the tradition of fictionalizing Tecumseh into the new millennium.

Tecumseh and Science Fiction

More than any other Indigenous American leader, Tecumseh poised on the knife’s edge of what might have been. It’s undeniable that Tecumseh made history in ways that cannot be overstated, but the point here is that he might have transformed our world into something we can scarcely imagine.

Herein lies the maddening “What if?” of Tecumseh’s tale.

At the prelude to and start of the War of 1812, Tecumseh led his pan-tribal Native army in coordination with Major-General Sir Isaac Brock, leader of the British forces, against the United States. Tecumseh and Brock formed a powerful partnership; they came to respect, trust, and rely on one another to a terrific degree.

Brock then wrote a letter to the new British Prime Minister, Lord Liverpool, in which he discussed his ally: “He who attracted most of my attention was a Shawnee chief, Tecumset [sic], brother to the Prophet, who for the last two years has carried on (contrary to our remonstrances) an Active Warfare against the United States—a more sagacious or more a gallant Warrior does not I believe exist. He was the admiration of every one who conversed with him …” Brock noted what he had learned from Tecumseh about how the United States “corrupted a few dissolute characters whom they pretended to consider as chiefs and with whom they contracted engagements and concluded Treaties, which they have attempted to impose on the whole Indian race.” He explained that the British would claim Native American loyalty if they could include American Indians in the final negotiations for peace when the war ended, and urged that the British recognize Indigenous rights to the land taken from them.

What does this mean?

Brock was so impressed by Tecumseh that he urged the British government to 1) give Native America a chair at the table alongside Great Britain and the United States when the final negotiations to end the War of 1812 were made, and 2) plan to recognize Native claims to lands the United States had annexed, should Britain win the war.

Either one of these actions alone would have redrawn the map of North America as we know it today.

But neither happened. Indigenous Americans did not have a say in negotiating the post-war boundaries in North America, and lands wrongly taken by the United States remained under U.S. control. The honorable and sympathetic Major-General Sir Isaac Brock, Tecumseh’s ally and advocate, died at the Battle of Queenston Heights in 1812. A year later, Brock’s vastly inferior replacement, Major General Henry Procter, abandoned Tecumseh and his warriors five minutes into the Battle of the Thames, leaving Tecumseh to be slain. Both Tecumseh and Brock were in their early/mid-forties. Had either or both survived the war—Tecumseh as a leader, and/or Brock as a leader influenced by Tecumseh—much might have been different.

Of course, no genre of fiction is better equipped to wrestle with a “What if?” than science fiction. Science fiction is the literature of the thought experiment, the story as simulation, the alternate history. Tecumseh’s tale has never ceased to fascinate—in part because Tecumseh’s dream of a unified Native America exercising sovereignty over traditional homelands is still a vision pursued by individuals and groups today—and science fiction has allowed authors to theorize different responses to the question “What would Tecumseh do?” In fact, one of the earliest modern alternate histories ever published, Guy Dent’s 1926 The Emperor of the If, involves Tecumseh. Other authors have followed Guy Dent’s lead; for example, both Eric Flint’s 1812: The Rivers of War (2005) and Erin Kushner’s Madison’s War: An Alternate History of the War of 1812 (2016) explore alternate histories of the War of 1812 and feature Tecumseh. On a slightly different note, the television series Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (1993-1999) repeatedly refers to an Excelsior-class starship named U.S.S. Tecumseh, thus making the ship and its implied tribute to the chief part of Trek franchise canon.

Orson Scott Card’s ongoing The Tales of Alvin Maker series of novels, short stories, and comics (1987-2015 and forthcoming) folds Tecumseh—who is referred to in the tales as Ta-Kumsaw—into a mythic alternate history of the American frontier. This serves as a stage for the coming of age of the series’ protagonist, Alvin Maker, who is supernaturally gifted with the “knack” for changing matter by force of will, and whose story loosely parallels that of Mormon leader Joseph Smith. Tecumseh’s historical brother the Prophet also plays a key role (and supplies the title for the 1988 novel and 2006-2008 comic series Red Prophet), although it is Ta-Kumsaw who deepens Alvin’s appreciation of his own potential by explaining that his knack draws from the vital power of the land itself.

Card’s Ta-Kumsaw exemplifies the magical yet natural power of the environment and those in harmony with it. For example, in Red Prophet, he walks on foot two hundred miles in a day–a feat reminiscent of historical accounts of Tecumseh seeming to be everywhere at once—because the land comes to his aid: “It would kill a man to run so fast for half an hour, except that the Red man called on the strength of the land to help him. The ground pushed back against his feet, adding to his strength.” Some critics might point to such Othering as a modern instance of romanticizing the Noble Savage; others might argue that environmental ethics is a necessary component in a series dedicated to the moral instruction of a young hero, and few figures from history and legend better represent a connection to and fierce defense of the land than Tecumseh. Both sides probably have a point.

An unusual and particularly powerful work is Beth Meacham’s short story “One by One” from the 1993 collection Alternate Warriors edited by Mike Resnick. Meacham imagines an alternate twentieth century in which “the Two Hundred Years War between the Shawnee Alliance and the European invaders” continues to seethe in the enormous half Native reservation, half mainstream U.S. state of Indiana, with acts of violence begetting more in an endless cycle. Rather than dying at the Battle of the Thames, Tecumseh had turned the tide of the war there. As Meacham writes, “the treaty that the U.S. had finally signed with Tecumseh’s grandson, just as the Civil War broke out, had guaranteed that the members of the Shawnee Alliance kept their traditional village sites and traditional farmlands.”

In one of the tale’s most visceral and disturbing scenes, Army Counter-Terrorist soldiers force two Alliance Warriors to their knees before a statue of the heroic Tecumseh and shoot them execution style. The moment effectively underscores the nobility of one who would never have sanctioned such treatment of enemy prisoners of war; it also contrasts Tecumseh’s example as a principled leader with the less-than-noble tactics of both sides of Meacham’s ugly, inherited de facto war. The fact that this Indiana conflict is between peoples who have lived side by side for generations and intermarried is one of Meacham’s points: “Half the people in this state are related by blood or marriage to the other half … I suppose that’s what makes things so tense. There’s nothing worse than a family fight.”

Perhaps the most significant work of science fiction featuring Tecumseh thus far came from Vine Deloria, Jr., noted Standing Rock Sioux academic and activist, author of works such as Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto (1969) and God is Red (1994). His distinguished career included serving as both executive director of the National Congress of American Indians and board member for the National Museum of the American Indian, as well as winning the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas.

During the U.S. bicentennial year of 1976, Christian Century created a series called “What If …? Rewriting U.S. History.” Deloria’s contribution was the first in the series, published for the January 7-14, 1976 issue. Written from the point of view of a very different 1976, its main idea is summed up in its title: “Why the U.S. Never Fought the Indians.” The fictional 1976 Deloria describes it by no means a utopia, but it is marked by the full engagement of the First Nations as influential players on North America’s stage at every step of the continent’s development.

No so-called Indian Removals or Indian Wars took place in Deloria’s alternate timeline. Instead, Tecumseh’s confederacy grew in the second year of the War of 1812 with the addition of “the southern tribes—particularly the Chickasaw and Choctaw,” giving his coalition the strength to stand apart, not only from its opponent the United States, but also from its ally the British. Tecumseh, therefore, became the architect “for the whole pattern of American development.” Deloria’s work reads as an indictment of mainstream U.S. attitudes and formal U.S. policy toward American Indians, as well as a reminder of Native potential.

In short, science fiction not only gave Tecumseh a new and different literary afterlife, but the genre also brought Tecumseh full circle, returning him to Indigenous hands and purposes.

As the fields of history, ethnohistory, and Native American/First Nations studies grow and mature, scholars are finding new tools to employ in uncovering and understanding the life, times, and impact of the Shawnee chief. Some, like Yours Truly, write books about Tecumseh aimed at the college classroom in order to introduce the next generations to his remarkable story.

It is Deloria’s counterfactual, science fictional vision in “Why the U.S. Never Fought the Indians,” however, that to date best captures the promise and the power of the once and future chief:

“With the western frontier secured against both Americans and British, Tecumseh was able to negotiate as an equal with the other two parties … as a result of the Treaty of Ghent the Indian nations received from the European countries the political recognition which had been lacking for three centuries; at that point, with their title to lands guaranteed and a process of negotiated sales under the supervision of an international tribunal instituted, the real history of the United States began.”