So long as an educated minority, living off all previous generations, hardly guessed why life was so easy to live, so long as the majority, working day and night, did not quite realize why they received none of the fruits of their labour, both parties believed this to be the natural order of things, and the world of cannibalism could survive. People often take prejudice or habit for truth and in that case feel no discomfort: but if they once realize that their truth is nonsense, the game is up. From then onwards it is only by force that a [person] can be compelled to do what [they] consider to be absurd.

Alexander Herzen, From the Other Shore

It does not do to leave a live dragon out of your calculations, if you live near him.

J.R.R. Tolkien

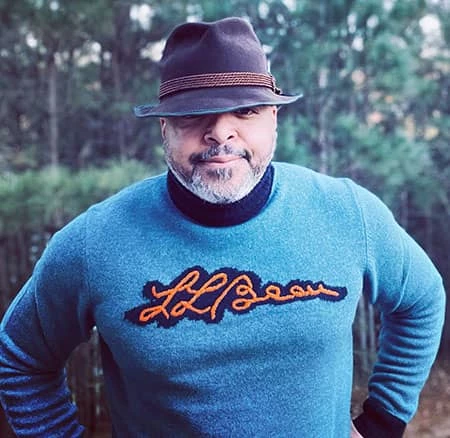

The jig is up. I use that phrase understanding its lexical and cultural baggage. There’s a tension in its etymology and I have summoned it, like an old family secret, for that very purpose. I’ve also conjured its particular history so I may say, we aren’t dancing to that tune anymore. Especially with a fake smile plastered on our faces intended to feign unequivocal acceptance of a fate of white America’s making, while simultaneously making its adherents and apostles feel comfortable. The banjo has fallen silent. We are no longer stepping and fetching. Making ourselves smaller for the comfort of others, or invisible altogether, has come to an end.

Welcome to the undiscovered country.

I get it. This probably feels confrontational to some of you, and that’s ok if that’s where you are. But let’s back up for a moment and talk about context. Let’s enter this conversation by way of misogyny.

In 1973, Paula Smith coined the term Mary Sue after seeing what she thought of as placeholder fantasy characters in stories submitted to her Star Trek fanzine. According to her, the young female characters in these stories were all so exceptionally sweet, beautiful, and good, that every other character in the story automatically loved them. Once the term filtered into the general consciousness of fandom, fans—mostly men—began using the term pejoratively. I vividly remember the term being thrown about the moment Star Wars: The Force Awakens dropped in the theater. It’s used as a way of delegitimizing the female protagonist.

But here’s my question. And it’s always been my question whenever the term comes up. What about Captain Kirk? How about Superman and Batman? Dare I mention James Bond, Ethan Hunt, and Sherlock Holmes?

Flash Gordon was a jock. Yet, somehow, he was able to thwart a master tactician with an entire space empire at his disposal. James Bond—and listen, I’m a fan—was one guy who was able to beat criminal masterminds with all the resources and well-armed henchmen in the world with nothing but an easy smile and, in some iterations, a few gadgets from Q. And can we talk about the white male revenge fantasy that is Batman?

Again, I’m a fan, so this critique doesn’t come from someone outside the fandom with no appreciation for the canon. But the lone orphan whose only superpower is his wealth who can beat people with actual superpowers by out-prepping and out-spending them? Have you seen the memes and their painfully on-point critique of the caped crusader coming out of nowhere to break the arm of the Gotham security guard who is working a double shift to buy his kid Christmas presents, rather than using his wealth to stop homelessness and wealth inequality in Gotham?

That critique and so many others are arising out of a genuine backlash against the unquestioned superiority of the white male hero in our fiction, put in sharp relief by the ever-present criticism of abilities, motivations, choices, and characterizations of heroes of color.

But let’s circle back to Paula Smith. Because she, and Sharon Ferraro—who launched the fanzine with her—also threw around the term Marty Sue and Murray Sue, for the placeholder male fantasy characters they saw in stories. Yet, for some reason (add a judicious amount of sarcasm to your reading here)—for some reason, those terms didn’t stick.

In his foreword to Jean-François Lyotard’s, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, Fredric Jameson writes:

This seeming contradiction can be resolved, I believe, by taking a further step … namely to posit, not the disappearance of the great master-narratives, but their passage underground as it were, their continuing but now unconscious effectivity as a way of ‘thinking about’ and acting in our current situation.

This isn’t a paper I’m writing for the master’s degree program. That was decades ago. But the point Jameson is making about the way master-narratives have changed how they function in our culture is relevant.

We have been predisposed to accept the white male protagonist, in all his forms, from knight in shining armor to deplorable human being tolerated for his “giftedness,” no matter how overpowered, unbeatable, and superhuman he may be. We do it without question. When no one can outsmart Sherlock we cheer. We no one can beat Kirk we nod with approval. When Batman can defeat any enemy because of “prep time” we don’t bat an eyelash at the utter idiocy of the notion. But the moment that character is a woman, or black, or queer, or anything outside the established norm of the western cultural industrial default character—i. e. white male—a certain corner of fandom rears its ugly head to cry foul.

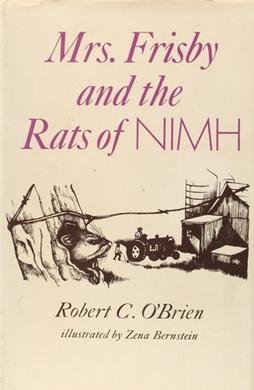

In elementary school, my favorite time of the year aside from Field Day was when the Scholastic fair arrived. It was absolutely magical. I loved it. They were just small mass-market paperbacks with a price tag of a couple of dollars each, arrayed on wire racks, but it was joyous.

I discovered Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH, Watership Down, and so much more. Even after the fair came and went, my teacher would pass around a thin color catalog from which we could order more books. We’d race home with our selections and get our parents to fork over five or six dollars so that we could place our orders. And then we’d pester our educational shepherd for weeks about when our books were going to arrive. Eventually, we’d return from recess one day and there would be an unremarkable, brown, cardboard box resting atop her desk. Around fifth hour, she would crack it open and hand out our books. She waited until our work was done for the day because she knew once we had our books we’d be unteachable.

We were a generation of readers who loved books.

Those small magical treasures led me to The Three Musketeers, Lord of the Rings, The Dragonriders of Pern, Elric of Melniboné, The Faded Sun, Dune, The Black Company, The Wheel of Time, The Sleeping Dragon, Jhereg (Vlad Taltos), not to mention comic books, video games, sci-fi movies, and Dungeons & Dragons. And through it all, one constant remained: the white male hero.

No one ever questioned their heroism, their abilities, their charisma, or the pedestal the culture erected for them. In hindsight, you can almost hear Shelley’s Ozymandias whispering in the wind, “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!” Kirk outsmarts Khan, Sherlock runs rings around Moriarty, Paul Atreides comes to Arrakis, is brought into a native tribe, and becomes their long-awaited messiah, with the ever-present trope of being more adept at the traditions of the natives than they themselves, and all the while fandom cheered.

As a Black man, I cheered less and less over time.

The current zeitgeist was inevitable. Fandom could have seen it coming. In the same way all those characters made white fans feel empowered, made them want to wrap one of their mom’s good towels around their neck like a cape and run through the neighborhood pretending to be their favorite hero—all the people seen as sideline people when seen at all, every person who didn’t see themselves represented in the canon, who always had to take an extra imaginary step to see themselves in the story—wanted to feel that same euphoria. We wanted heroes that embodied our heroism, our valiant streaks, our daring and ingenuity.

At some point in college, while reading yet another installment in the Wheel of Time, it dawned on me that I wanted to write science fiction and fantasy. The preeminent reason was a love of the genre in particular and writing in general. But the subtext of that desire was to write sci-fi and fantasy with protagonists that looked like me. When I finally did and broadened my participation in fandom to include conventions as a guest author, a participant in podcasts, zines, anthologies, and all the rest, I discovered that the idea of capable, charismatic, genius protagonists of color (of ALL peoples pushed to the margins, but I’m focusing on how for every one Ben Sisko there are fifteen hundred womprat-shooting Skywalkers)—that idea was dismissed by some as unrealistic, overpowered, illogical, “just self-inserts” and not worthy of being taken seriously as heroes and heroines in good stories. I’m still wondering how anyone can see those as anything other than ridiculously laughable arguments.

Well, I’m afraid I have to announce something some might find unpleasant. Captain Kirk is dead. I don’t mean that he died in Star Trek: Generations helping Picard beat Soran (notwithstanding a “resurrection” by the Borg in a novel). I mean as a stand-in for the unfettered reign of the infallible white male hero. Marty Sue, Marty Stu, Murray Sue, or whatever you wish to call him… is facing a cultural curtain call. While there will almost certainly be a grimy corner of fandom that continues to try to sell the rest of us on a world where only the white guy gets to be unbeatable, there are far too many new writers and creators who love science fiction and fantasy, who look like Benjamin Lafayette Sisko, Michael Burnham, Rey, T’Challa, and Shang-Chi, writing and creating strange new worlds, boldly going where no white male protagonist has gone before. And as much as that may bother some, it’s making many more rejoice.

The jig is up. And not a moment too soon.