The colour is full of shade and smells like crusts of fruit. Crushed guavas, warm wet clay—that’s the sweetness and mushiness about the forest. A tepidness too. And then there’s a whiff of soured yam, unwashed body. Something old sniffling in the shadows.

Eyes pore over your hollow within, ticking, ticking with your heartbeat. But the hollow is dead cassava dry—all surface and dust. What sound will fall when you press your ear to its longing? Perhaps nuances of self-reflection beckoning the moon’s return.

§

You are eighteen months old.

A crunch of tyres, then squeals of children tumbling out of a foreign car. Your mother owns sandals but likes to walk barefoot. This is how she greets Aunt Prim, who is layered in batiks and swirling in a smell of flowers. She’s approaching the boma under the blaze of an orange sun. Your cousins, Tatu and Saba, are giggling, whispering, nudging each other.

“Abana banu! These children!” Aunt Prim is all sharpness. Sharp eyes, sharp nose, sharp ears. “I heard what you said!”

She grabs a stick from the ground, makes to chase your cousins, but platform shoes don’t take her far. Her tongue clicks. Her stick waves from the distance. Aunt Prim is nothing like you know. Because your mother is pillow-soft, her voice tender like the feathers of a baby bird. She’s hooked you on her arm, your fat legs astride her waist. Her sweet brown eyes, her dancing dimples. She smells of sugar bananas—small and thin-skinned—on her chest where you rest your head.

“Sissy Prim. What do you bring us from the city?”

“Flour, sugar, and these two urchins. Look at them.”

“Doing what?”

“Mischief. Can’t you see?”

“Don’t run it up. They are young. See how you make them hush like spirits.”

“Evil ones.”

Silence, then a scatter of feet. Titters spilling everywhere, as your cousins stampede around the hut in a shroud of dust.

“I swear!” says Aunt Prim. “Weye! Useless as mud.”

Your cousins still running.

“Tatu!” She’s the older one. “Wait ’til I catch you!”

“And then what?” asks your mother.

“She’ll see.”

“Don’t fall on the child with a hammer.”

“Mphyo!”

Your world is small yet familiar, framed in textures and shapes. Sometimes you see darkness and lizards, cats nudging and gliding between grown-up legs. You touch what you know. Listen to what you don’t, but still touch it. Trust or instinct is not your diplomacy. It’s all about repetition, endurance. Curiosity and hunger etched in your living.

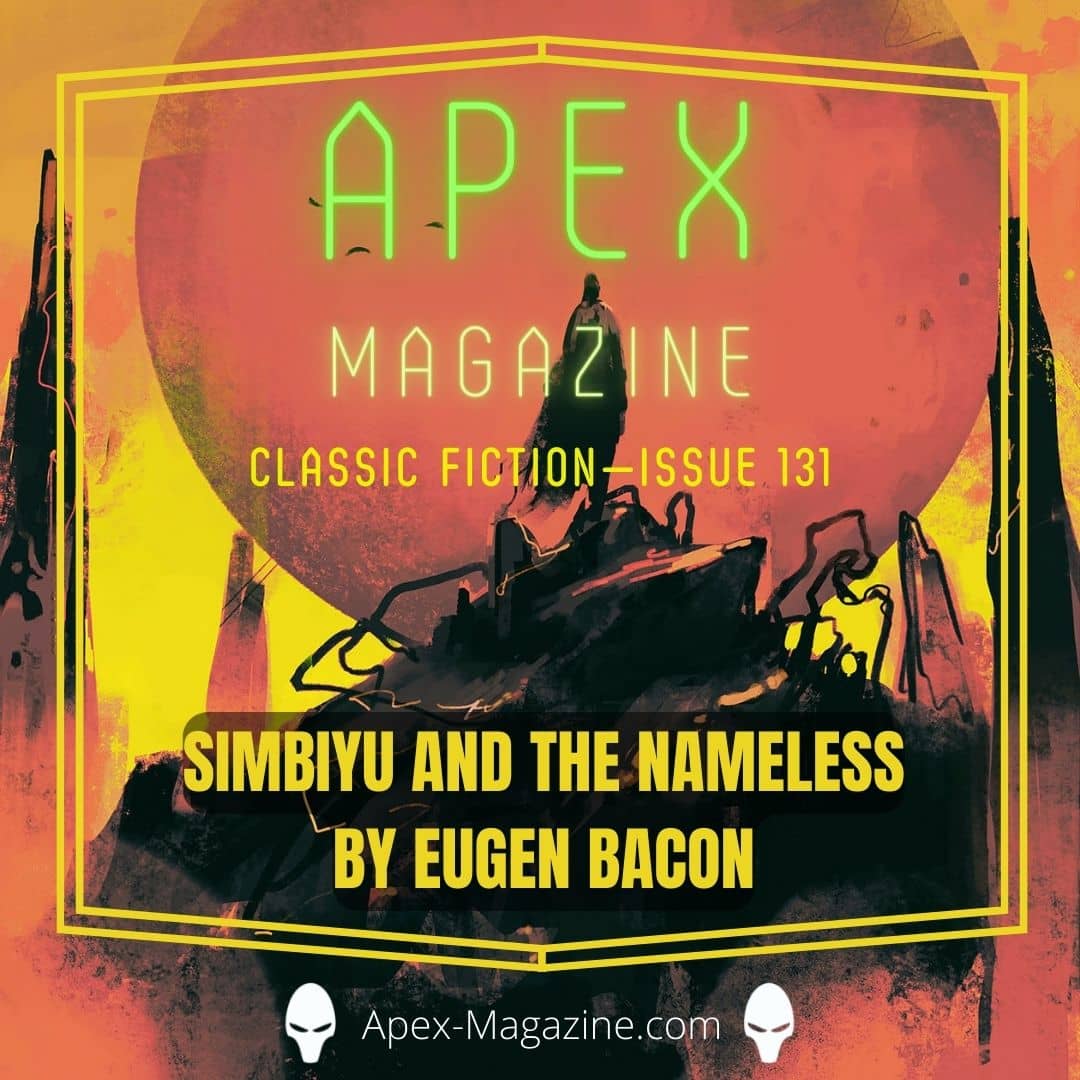

“Tatu!” Your mother locates the cousin behind the fat waist of a mango tree. “Take Simbiyu.”

“I don’t want to.”

“Because why?”

“It’s hours of boring.”

“Rubbish. Come on then, quick. Your mother won’t eat you.”

“But she might!”

You whimper a little as your mother loosens you from her hold as she presses you onto Tatu’s back. “Saba, go inside. Fetch me a wrap.”

He runs.

She rubs banana smash off your face with spit and a thumb. She takes the floral wrap from Saba, secures you on Tatu’s small back. “Now off you go. Stay away from the river. Be children. Be alive.”

“Like a drum?” quips Tatu, kicking off her shoes.

You gurgle your glee and bop on your cousin’s back. Her naked feet race away from the homestead, past a few huts, some goats, and grumbling chickens, and into the tree line.

“Wait for me!” cries Saba.

It’s an uneasy sanctuary for play. But Tatu has chosen it. She zips into the forest full of spidered twines and shiny leaves—green and swollen like avocados, but they smell of the watching dead.

“I don’t want to go there,” says Saba, stalling his feet.

“Iwe! Don’t be a coward. Just come!” Tatu loops through the trees. She doesn’t care that Saba has chosen to run back home. She unknots you, plants you against a slanted candelabra tree and its bad milk. A perch of white-backed vultures with sharp beaks are on the tree overlooking the river with its white wash where you’ll likely die—not from the water’s malice that is of a different kind, but from a bask of crocodiles burrowed in its mud and blinking to darkness.

The river is changing. You know this without knowing how, or why. Tatu doesn’t notice. She’s poking in the mud, digging for crabs. A black octopus climbs from the water’s surface. A mist that whispers a name. You understand it. You’re one with it, bopping your anticipation.

They find Tatu’s husk, and you—crawling and full of play around her shrivel, babbling a name.

§

You are four.

Tumbling down the village with your little friend Uhuru from the hut next door. He’s your companion now. Your mother is distant, busy with farming: yams, sweet potatoes, and tomatoes to sell at her stall in the market.

You feel the shift in the air before you see it, before Uhuru’s squeal.

Silence is a dog rooted on the ground, no heart behind it. Smell is a non-event whose jaw is wide open, eyes glassed in shock. It’s the maggots that carry an answer—slipping in and out of intestines torn from the dog’s belly. Worms coiling, uncoiling, negotiating with the corpse, draping around each other in a sepia slime of focus.

Uhuru sees the dead dog and its maggots, but you see more. He’s unaware of the fragment—something broken—and it has chosen you. That something is the shade of a tree, a lurching darkness assembling, disassembling. A menace approaching, human, nonhuman, waving tentacles.

It’s the octopus from the river. A shadow jerking and crawling like the maggots but with a story, and there you are. Your mouth is moving in silence, unfolding words that are a breath in a messy language full of space. And you’re ready and available, full of history and a future, just unwilling to once more hear the name.

“Run!”

As if Uhuru needs encouragement.

§

You are five.

You don’t remember much of what happened—it was a blackout. They say you were sitting at the edge of the forest, all giddy and merry inside the circle of a serpent’s coil in broad daylight, mumbling a name.

The creature was lethargic, a swell in its belly. Village men pulled you out of the circle—only then did you cry like someone was ripping off your limbs. But the rock python was too lazy to move. They sliced out broken bones and what was left of Uhuru.

It changed how people saw you. Now, they whispered.

At first, they poured holy water and crossed themselves when you passed. In time, they forgot what you didn’t.

§

You are seven.

You know how to mingle, but it’s not a school day. You like the sweet and mushy forest near the river. It’s cooler on the skin here. Oranges and purples in the bright green foliage, flowers drooping, sky-craning, leaning into you as you walk by.

The rogue sisal belongs near the candelabra tree but today it is here. Chorused trilling, squeaking birds. You adore nature in its glory. Look, a shrub, weather-trimmed to resemble the bum of a gorilla facing away. The chwee chweee of a cousin bird hushes with the cough of a giant bird flapping its wings above the broad star-face of wild cassava leaves. The sound of water running. You can smell it: wet soil and reed.

No one is here, just the birds and you. You forget tussles with harmless children who sometimes tease, and you all but hold back from calling up a name. You’re nothing like them, the village tots like Juzi or Vipi or Bongo—never curious about the skull of a dead zebra, the neck of a fallen giraffe. You discovered them at the edge of the forest. You once saw a leopard drag away a child. People are afraid of this wilderness, not you. You’ve told no one about the cave and its dripping of warmish water near the shores of the murky river hiding crocs and snakes.

Today you’re here where it’s dry but cooler on the skin, the name of an entity in your head. But it won’t come.

§

You are nine.

You are more and more in your head, but perhaps it’s your mother’s guilt or penance that farms you out to Aunt Prim. Your mother walks you miles and miles from the village and your river, from dawn to noon, until you reach a market. There, she haggles about the price of a ticket and puts you on a bus.

“Your aunt will be there when you reach.”

“But I’m hungry.”

“Eat the oranges and casava in the handkerchief I gave you.”

The bus pulls into a town station at dusk.

Aunt Prim is there, all right, layered in batik, swirling in a scent of leopard orchids and kudu lilies.

Slap!

“But I didn’t do anything.” Your hand on your cheek.

“That will put it right out of your mind to do anything,” she snaps and hauls you to her car.

“Where’s Saba?”

“Boarding school, like you should be.”

You look at her. You don’t have to say the name in your head because you feel it. The octopus mist is swirling, swirling inside. All this way … how did it come?

That night Aunt Prim wakes up to lizards crawling in and out of her hair, up and down her body. She sees a yellow-eyed cat sitting on the sill of her bedroom window, in the blackness looking at her.

The incident creates the grim reality of your tacit agreement with your aunt to be civil to each other. You do your chores, do your school, where students and teachers give you no mind, and you prefer it that way: left alone, except on the football field. Aunt Prim lets you be, and you let her be. Sometimes she gives you Saba’s comic books: The Adventures of Tintin.

In this world, you run up tides and variations by intuiting. Your entity is here, a spectre that enfolds you when you close your eyes until you reach the edge of reason. In life’s lessons, will your sixth sense do you solid? Or will it dot your portrait of purpose, all obscure?

Right now, you don’t know. Each day is a swaying floor that smells of city, sea, and trap. You should be angry, fatigued from it: who’s scripting your part?

A dream with a name is your handhold.

§

You are thirteen.

A scout spots you playing football in a stadium. You’re clean with the ball, hitting the scoreboard. The other team is wide, nowhere near. Your own team is a shocker, but you’re the most valuable player.

The scout is leaning against a post, scribbling notes on a sheet held on a clipboard.

A blackbird with an orange beak hops on your path, vanishes into air.

A name that is peril and chance slams like a door in your head.

§

You are fifteen when they clear you for travel. Your scholarship has come through. Aunt Prim is still wary but today all teeth, a wad of money tucked between her breasts.

“Get settled there and send for your cousin Saba. You’ll make us proud.”

Does “us” include your mother? You haven’t seen her in years. Sometimes, you wonder about her, then forget. You lost your mother the day Tatu died. She stopped breastfeeding you that same evening, and her touch hardened.

“Jump in my car. I’ll drive you to the airport,” says Aunt Prim.

“I’ll take a taxi.”

The road to the airport is full of potholes. The foreign contractor used cheap tarmac, and someone put a lot of money in their pocket. It’s midnight when you pull along the kerb to the international swing doors. “Keep the change,” you tell the driver. The scout and the people he represents are either very generous or keen to have you. You step out of the cab and further from all you know. It’s a story for no tabloid, only you are listening to its tale. You understand all you’ve lost forever, yet it’s the answer for right now.

You arrive at the checkpoint without phoning your shoeless mother who may be waiting for your midnight news. For the first time, you understand both dying and torment and the yawning schism of passing over.

You’re sullen all the way to Melbourne Tullamarine Airport.

Six a.m. A queue of people at customs. A thumb sucker catches your eye, barks his cry into his blonde mother’s shoulder. Perhaps she’s an expat. She’s wearing a T-shirt that says: African drumming: be alive. It reminds you of Tatu.

The uniform’s face when you reach him is a stop sign. He demands papers, gives you a look that says you don’t have them. But you have them. There’s no ambiguity in your compliance. Still, he enters a dangerous discussion.

“Empty your pockets.” It’s full of notes—jottings that remind you where to draw the line. “Your phone,” he says.

“Enough,” you say.

He starts to bark orders, but the smell of dead bones has a point. It also has a name. Alarms are beeping like mad. The uniform’s mouth is opening and closing, like that of a fish out of water. His skin is losing lustre, in fact greying. Restraint, for you, will come with age. Today is a life behind you and a fuckwit between you and the life ahead.

Your ride is a big white van with a sign: A hive of bees? A sack of guavas? Goget.com. The man driving it is not the scout. He’s a scruffy white man with ash on his head and a back-turned cap. You saw enough tatty whites in the planes and the airports, stopovers in Dubai and Sydney, but attributed it to a lack of flying etiquette. Now here’s another one who held up a sign to retrieve you at Arrivals. A sign that said: Simba Yo.

You tap him on the shoulder. “That’s not how you say my name.”

He grunts.

He’s not a man of many words. He drives along the labyrinth of the metropolis. You reach the college campus, and he throws your swollen suitcase off the van.

You’re not sure whether to tip him. You pull a note, mindless of its value, and offer it.

“Nah. Keep your money, mate. We don’t do that in Melbourne.” He reverses the van, drives away.

You report at the main office arranged with phones and computers. It has pale walls and high ceilings. Glistened trophies and framed certificates stare at you. The girl behind the desk is a topaz-eyed nymph with burnt-orange hair.

“You’re early. Semester starts in a week.”

You sign forms. She gives you a student card, keys to your room, an entrance fob, and a map. “Not many students around, but you might bump into the odd teacher.”

You drag your suitcase into the grey monolith that’s your dormitory.

Later, you’ll take a walk to acquaint yourself with this new world full of cars and shops and houses built like wedding cakes; you saw a tiered one when Aunt Prim’s friend got married. You’ll discover a restaurant that serves wok-fried prawns with lemongrass, curry leaf, and shrimp. You’ll wash the food down with water, not a glass of white.

On your way back, you’ll go past a young woman with a face swallowed in sunnies, dragging a leash and Tintin’s dog. She’ll take one look at you and remember to remotely lock her car.

You connect early, though you don’t know how to read her, the new one. She comes at you on campus, peering through a camera. She lowers the lens. Big gold eyes shimmering on her face.

“Yer ’ave a look like a man on a mission ter forget a past.”

“I’m not sure,” you say.

“Then yor name’s Tipsy.”

“It’s whatever you like.”

“Just messin’ wiv yer. They call me Mali.” She extends a lingering hand that fits in your clasp. She’s attractive: full lips on a triangle face. Hesitant smile. Hair so black it’s blue, braided in rows and tails on her head.

“I wasn’t expecting that accent from a black girl.”

“I’m not sayin’ anyfink about yor accent.” You look at her, amused. “I’m bloody well British. Media and Studio Design. Are yer also on a scholarship then, guv?”

She’s wearing a sunflower flow, bohemian in style. It waves with the wings of a butterfly. She’s a twist in your story now—your gut tells you this girl is important.

“I’m a lesbian,” she breaks your heart.

Mali shines. The longer you know her, the shinier she gets. It’s not just the gold in her eyes—sometimes she’s splashed in a beam of light from the sun.

She introduces you to grilled hunky dory and deep-fried chips. You miss chicken hearts and gizzards, slowly stewed in a pot on a three-hearth stone. Simmered with four sprigs of coriander and natural pink salt from the flamingo lake.

You take economics. The lecturer is easy on your requirements for tasks and assignments. What matters is the field. The coach teaches you to play a different kind of football that uses hands and feet. They call it footie. The game has marks: players climbing others in leaps to catch the ball. It has boundary throws. The coach makes you a forward, not a ruckman—you’re athletic but don’t have the height, even though you can fly.

First match, first quarter, you’re a showcase: three goals on the spot. The octopus is in you everywhere, your hands and legs fully tentacled. Bounce, bounce, kick. On the field, like this, you’re one with the team. Inside kick, handball pass. Clean disposals, no waste to the dying seconds. Off-field, you’re solo. Not counting Mali.

§

You are seventeen.

But today is its own narrative. The octopus is asleep.

Before you fall, the ball has legs and accuracy—for the other team. The field is yellow with night lights. Shadows and smells: sweat and feet. The other team’s players are everywhere. The match is a brawl, short shorts as you fight. Shoulders and chests bulldoze you to the ground. Knees and shins find tiny gaps to the post. The other team’s star player has a left foot that’s a mongrel. Nothing you do bangs the ball on your end.

Your coach is filthy about this, his hands and mouth severe. But your body is wrong, your kick a real mess. Your skin is ill-fitting—that’s why you fall.

What you want to remember is the name in your head that stands you up. The name that comes when your mind connects with a memory and latches on to it. It makes you right, just so. The name that’s a voice and a ghost and a storm all at once. The name that makes you slippery through the forward half as the other team gains metres and besieges you. The name that fuses the ground and the sky like a clash of heavens and hells on your shoulders. It’s a release that floats your ball long and deep and the match is changed.

What the devil? It’s great. Now you understand that the entity is not always harming, it’s gifting too.

§

You are eighteen.

You celebrate with a trip on a leased car. A three-hour drive via the CityLink to the Hume Highway that merges onto the Northern Highway. Two hundred and thirty kilometres to Echuca.

“Blimey, right, I forgot the camera.”

Mali—the lesbian friend you can’t read—is all eyes and dimples that remind of your mother, yet not. She’s the one driving, she has a licence.

Two years now, she’s been giving the right vibes that could be wrong. She has slowly hijacked your life in a romance that will never take.

From when you first saw her, even as the campus grounds spilled with students—red ones, pink ones, olive ones—Mali and her cloaking of light are spottable anywhere. You find it refreshing to be around black skin, though she speaks funny and insists on pointing her lens at moving targets: birds, cars, people, you, mostly you. Saying, wow, wow, as if she sees something you don’t.

Her photos of you are up close. A soldier’s crop. Big square face. Thick black brows that are better less. A wide nose. A gobbling mouth—she caught you in a yawn. You wonder what she sees in you. Still, you can’t read her. She holds away from more. Or is it you holding away, unsure if she just really likes you, or is bi?

“As I were sayin’, Simbiyu, me pops. He’d been married, wot—thrice?”

You look at her and see sparkles. She’s shimmering.

“I never knew my father,” you say. “Spoils of war.”

“Scars, right, yer mean, isit?”

“Too good at reading me.” You’re thinking: Shouldn’t she be the one?

“Yer make it sound terrifyin’.”

You’re in trackies, but the rented four-sitter is all shiny inside, gears and buttons. She glides, purring all the way down a lonely country road, the sun bearing down, a scorch in your throat.

You were once a child with a lacking story, and now worry about what’s too far gone for sadness or anger. But you already determine that what should be is a slaughtered treat. Nothing will resurrect the impossible. Work is never cut out for you. All you can do now is comfort yourself under the looming moon’s unreadable gaze.

Mali drives long and north towards a country town with paddle steamers on the Murray River. The evening sun is a watercolour on the horizon. Clouds frown malcontent into meantime lands. Echuca is a ghost town. You’re too late for the paddle-steamer, and everywhere is closed. Look, what’s this: a pub named Parfitt. It’s yet unpatroned but spilling with brash country music.

Please, no dogs, says a sign on the wall behind the service counter. But all you see is a memory far too big, a walking contradiction to nowhere stories. The pub with its fading décor is not the kind you pictured. A float of feathers lavishes fusty walls, but there’s a hook for a coat. The man at the bar is wearing a sweater. He has eyes that could be your lost father’s, his arms folded, legs akimbo. Box face, swirly curls all grey, the nose of a prince—all haughty like. He’s built like a fridge but there’s heat in his dislike. His eyes come and go to the sign on the wall, then at you.

You look around. There are no dogs, just you.

Mali is sparkling. “That says a bit. Like a bit.”

You don’t need to summon the name. You and the river octopus are one. Your head falls back, your tentacles spreading within, without. Your eyes close, your feet off the ground. Your eyes open to blinding light. You blink. All is changed. Fat toads are hopping on the counter, sliming the floor. Hundreds of lizards knocking glasses in slow-motion hours going without protocol. The man at the bar is making a noise that’s a groan inside a croak. A toad is lodged down his throat. His legs have the shakes. He’s deflating inside his sweater, a man-sized doll losing air. The desiccation in his skin … The shrivel of hair on his scalp. Centuries consume him. You look at your hands—you’re a shadow. Your mouth is moving in silence, your body lurching darkness.

A voice inside the bright light says, “Me word. I don’t ’ave me fuckin’ camera, init? I knew yer were special.”

You step back into yourself on solid ground, but your head is swirling. Suddenly you feel alone, and alone is not so fun anymore.

“Simbiyu.” Mali’s luminescence is reaching, your name is a caress on her lips.

As you wonder when she met her Cthulhu, she offers her lingering hand. You hesitate, then take it. She snatches you out of the pub and drives across a railway, past its station to a place you’ll lean into each other, chest to shin, heads touching. Waiting—for what?

You’ll spend the night at a family motel with Wi-Fi and free parking.

§

You are twenty-three.

Your team has been in the “top four” years in a row: twice grand finalist and two cups to show for it. You are the most medalled player, constantly making headlines. You wear twice-shined moccasins. You own three cars and a tiered wedding-cake house on Summer Street in a leafy suburb.

You pay for Saba’s tuition—he’s family. Wema hauozi, says the adage. True: generosity never rots. You send money home to Aunt Prim and have built a storeyed house for your mother—what’s family? She still walks barefoot, they say. You put electricity and tap water in the village. They finally cordon it from the wilderness when two elephants go rogue.

There’s a sweetness in your bedroom, a mushiness in the air. A tepidness too. It doesn’t matter when crushed guavas and warm wet clay show up, or when a whiff carrying ghosts of soured yam dumps itself with a scratch on your chin.

A crack of lightning and the devil himself plods from twilight. Then he’s you, and you’re offside in your leap from the bed. You land knees and knuckles on the ground. Your skin heals and takes you back to yourself and your bed. The devil smiles and wets his parched throat from a brook as you lie awake counting words and dreams sprouting from a future that insists it knows what’s best before sunrise.

You look at Mali, blanketed in silver light. Glittering in deep sleep beside you.

You remember with longing your once pillow-soft mother. Her sweet brown eyes and dancing dimples. Her voice, tender as the feathers of a baby bird.

You finally understand the nameless. And the darkness that rose from the river those many years ago—how it chose you. Because it’s also you.