Sure, “blood is the life”, as Dracula’s Renfield would have us believe, but closer examination reveals a plethora of nuances to that phrase, provided we listen close enough to the rantings of a self-admitted lunatic.

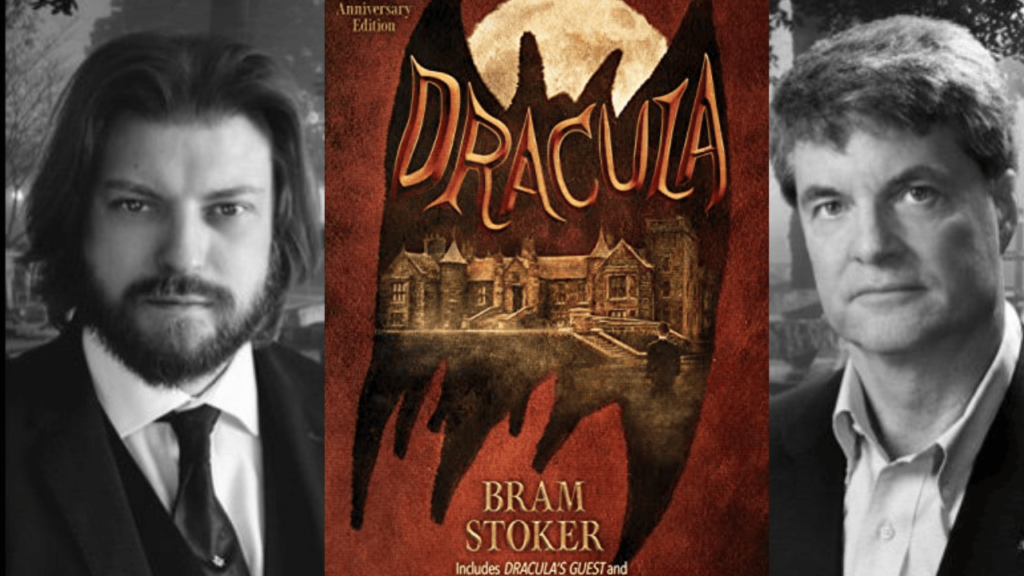

I recently had the honor and pleasure of chatting with Dacre Stoker, a best-selling author who’s made it his life’s mission to uncover all the historical artifacts connected to the life and work of his great granduncle, Bram Stoker. Through our conversation, I learned far more about one of Bram’s most memorable characters, Renfield, than anyone could have guessed. By slipping behind the curtains, we learn what’s truly written between the blood-red lines.

Top of that list is the mostly neglected compassion for and the proper treatment of those suffering with mental illness. Sure, times were a lot different while Bram was writing Dracula between 1890 and 1897, but I personally can’t think of a more relevant time to hold a glass to the wall and listen to what The Fly Man was trying to tell us all along.

The values and statements expressed in Dracula through Renfield likely started with Bram’s mother, Charlotte. Mrs. Stoker didn’t allow social standards to interfere with what she knew to be right and just. For example, an elite all-male Social and Statistical Enquiry Society in Dublin didn’t generally grant attendance to women, let alone permit them to read papers of social significance. Clearly Mrs. Stoker didn’t get that memo (and likely would have torn it up if she had). Charlotte Stoker would not be silenced. Sometime between the 1850’s and 1870’s, she attended and read papers to advocate for better education of the deaf and mute, as well as how to judge if somebody was criminally insane. (Perhaps not so coincidentally, Bram’s oldest brother, Thornley, would eventually be responsible for granting licensing for experimental surgery on the most severe mental health cases, but “only if absolutely necessary”, the same words Bram’s fictional Dr. Seward uttered to Doctor Van Helsing.)

Factor in Bram’s early career as a clerk in a Petty Sessions Legal Department, which handled matters such as minor, larceny, assault, bastardy examinations and arbitration, and we get a clear picture of the kind of social justice and human equality Bram and his family held dear. These qualities undoubtedly provided much of the fabric from which Dracula was woven. While all three of Bram’s brothers were doctors, to suggest Thornley in particular was an influence on the accuracy of Dracula when it came to the medical stuff would be an understatement. After all, who better to have over your shoulder as you’re writing about the brain surgery Dr. Seward performed on the battered Renfield than an older brother who had performed that exact surgery on at least three separate occasions? With that kind of realism employed in the telling of such an iconic story, it’s worth noting what real life fears Bram worked so eloquently into the tale.

As if appointed to do so, Renfield represents the Stokers when it comes to their stance on the often misunderstood, dire consequences of mistreating and neglecting those who’ve been stricken with mental illness by way of genetic lottery or some deep-rooted trauma. Considering Renfield does eventually come to realize the malicious control Dracula cast over him, one can assume Bram felt sufferers of mental maladies were hardly without value if given a chance. The challenge, both then and today, is convincing the most powerful influencers there’s a better way to approach our mental health crisis than banishing the psychologically sick to mental prisons where they’re often subdued and forgotten. As Dacre Stoker explains, “At this time (when Dracula was written) in society in places like Dublin and London and I’m sure many other sophisticated and advanced countries around the world, people with mental problems were simply put into prisons. They had no real medical way to deal with these folks. Again, big issue with Mrs. Stoker. Thornley Stoker worked not only dealing with physical problems with people, but psychological as well. He was sort of cutting edge trying to figure out how we can better serve these people.”

Remember that scene where the good Dr. Seward was performing brain trephination surgery on Renfield? Accurately depicted thanks to Bram’s privileged resources, it was not bizarre for patients to ask for a drink of water or chit chat with their surgeon while their heads were literally open to any possibility their surgeon had in mind. Perfectly paired with Bram’s compassion for the complexity of the human condition, we’re treated to a revelation of what truly lurks beneath the unenviable shell of Renfield’s affliction. It’s during this scene when, unlike patients under Thornley’s instruments, Renfield confesses to what sneaky things his undead master has been up to and warns them of the grave danger Mina is in. Sadly, Renfield succumbs to the beating he took from Dracula, but not before seeing the goodness of faith in good people as he unceremoniously joins the band of heroes. It’s in this moment that Renfield’s innate compassion for decency shines through his illness despite having been Dracula’s brainwashed servant. In return for Renfield’s sacrifice, a lasting remnant of wisdom is captured and held against the deterioration of time. Of course, as cliché as it sounds, when it comes to our Life with a capital L and the human connections thereof, it’s what we do with it that counts.

Bram’s effort to convey his Fly Man (a name he changed to Renfield only when handwritten into the final typescript) as realistically as possible should come as no surprise. It’s on record that Bram had visited prisons, interviewing criminals and folks with mental illness. Always the sponge for absorbing information, Bram observed their verbal patterns and studied what their makeup was about. As a man of science, compassion, and justice, Bram took what he learned and built Renfield as a powerful statement of how to not only do better, but how to be better for those who need us the most, whether they suffer from dementia, psychosis, debilitating anxiety, or any number of mental ailments. Dacre tells us, “You know, there’s more than meets the eye. Let’s not just shove them away and forget about them in these horrible institutions. I think that’s the message Bram was trying to give.”

Suffice to say, through the characters of his creation, Bram has left us much to study regarding the value and treatment of the most vulnerable minds in our communities. It’s a study as worthy of our focus today as it was 126 years ago when one of the most important gothic tales of our time was first published. While the consequence of not treating those in mental or emotional distress better likely won’t result in an undead creature of the night relentlessly feeding on our blood and misery without a lens of compassion and transformation, it’s time we realized it’s our current systems that often serve as vampires instead of the care and hope they are meant to provide.