When I was a kid, I was a huge fan of the Back to the Future movies. I was seven when the first one came out in July of 1985, and my dad, himself a film aficionado, took my younger sister and me to see it in the theaters. The first movie that my sister and I saw in the theater on our own was Back to the Future II, in 1989. And while my personal favorite is Back to the Future III (mainly due to the adorable romance between Doc Brown and Clara) it’s that second movie that has gotten a lot of attention lately. You may remember that it’s the one where Marty McFly and Doc Brown travel to the future. October 26th, 2015, to be exact. Which means “The Future” was a little over a year ago. As that date approached, many marveled at how different the actual future was from the shiny, manic future of flying cars and self-drying clothes. Somehow they managed to have hoverboards that didn’t explode … and yet they also communicated by fax instead of email.

You can read the original short story "I Remember the Future" by Michael A. Burstein here.

Abraham Beard, the protagonist of Michael A. Burstein’s Nebula-nominated short story “I Remember the Future,” is also living in a future that is different from the one that he expected. As a peer of Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, and Arthur C. Clark, Beard wrote stories of a future that saw humanity traveling to the stars. When we meet him, he’s an old man, and the future he had spent his life creating hasn’t come true. The American manned space program has stalled, and instead of interstellar travel and colonies on Mars we have the Internet and blogging. To compound his frustration, he has come to believe that his stories hadn’t been his own ideas, but rather messages from the future, a future that now doesn’t seem to exist.

Beard’s devotion to the future of the past, both in creating it initially and in mourning its loss, has damaged his relationship with his only child, Emma. As we watch his painful interaction with her, we are given flashes of the future that Abraham created through snippets of his novels. We’re brought to wonder what place this man has in a world that seems to have left him and his future behind. By the end of the story we have an answer, and (no spoilers!) it’s not what you might expect.

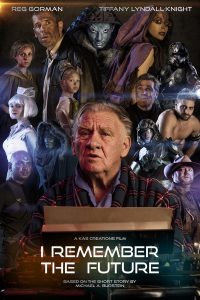

In 2014, Australian filmmaker Klayton Stainer adapted Burstein’s story into a short film starring Reg Gorman and Tiffany Lyndall-Knight as Abraham Beard and his daughter Emma. In addition to being very faithful to the original story, the film is a love letter to classic science fiction, with the snippets of Abraham’s novels rendered into beautiful scenes with sweeping, majestic music that masterfully evoke a sense of wonder and awe. Those scenes run a strong counterpoint to the quiet emotional intensity of the scenes between Gorman and Lyndall-Knight. The audience is invited to exist, like Abraham, in these dual worlds of the present and what, according to the science fiction of Asimov, Clark, Heinlein, and Beard, the present should have been.

I had the privilege of interviewing both Michael A. Burstein and Klayton Stainer about the story and the film it inspired.

§

Michael A. Burstein

§

APEX MAGAZINE: Writers are often asked where we get our ideas, and I found it really funny that Abraham has the answer down pat: he’s getting direct communication from the future! Do you have communication with the future?

MICHAEL A. BURSTEIN: I do not! I wish I had communication with the future. The way “I Remember the Future” happened was that Apex had agreed to publish a collection of all my stories that had been nominated for the Hugo and the Nebula. For a collection, you want to make sure to provide readers with something new, so we provided two new stories. One was another story in the Broken Symmetry series, and then I needed a title for the book, and I was going to have a story to go with the title. So I did a contest on LiveJournal. I opened it up and said, what’s a good title for a collection of my stories? It was a high school friend of mine, Andrew Mark Green, who came up with the phrase “I Remember the Future.”

So here’s this title. What is this story going to be about? And that’s how I started developing. Okay, maybe there is a guy who is remembering the future. How does that happen? Then I started going to my themes of how will we be remembered, science fiction writer, all of these pieces started kind of being put into place.

AM: “I Remember the Future” resonates with a lot of people. Why do you think that is?

MAB: You know, I thought it would resonate a lot with the people who like older science fiction. I wrote a story about a guy who lived through all that. The little vignettes from his novels that I put in there were supposed to be representative of what science fiction was like when he was writing. The story did not get nominated for a Hugo, but it did get nominated for a Nebula, so it obviously resonated with science fiction writers who were members of SFWA at the time. And I can see the appeal it has for filmmakers. You have this framework story where you’ve got the writer, you’ve got his grown daughter, they’re just in a house. But then you have all these little pieces drawn from these novels. It would give a filmmaker a chance to say, see, here’s what I can do. I can bring to life this scene of archaeologists discovering an ancient library, I can bring to life this scene of people about to board a spaceship. Then, in the case of Klayton, I can do it relatively inexpensively. I mean, the guy was a student. This was his college thesis, I think.

AM: He did a really good job with it.

MAB: I was blown away. I thought it was beautifully done. It was incredibly true to what I was trying to say, and he put in extra layers. If you look at the website, all these throwaway characters in these vignettes are given back story on who they are. I don’t want to say anything that’s a spoiler for people, but one of the things that I thought was a very interesting creative choice was how the actress who plays the captain of the spaceship was the same actress who plays his daughter. I thought it really showed something in Abraham’s world. He can’t relate to his real daughter. And that’s the tragedy. He’s only able to relate to the daughter in the stories he thought he was creating.

AM: He doesn’t seem to have a very good view of his daughter.

MAB: I want both Abraham and Emma to be sympathetic; that said, there’s definitely a barrier between them. I wrote this story the year between losing my mom and my daughters being born, so I didn’t really have a comparison to be on Abraham’s side of parenthood. That said, it wasn’t that hard to envision this as somebody who maybe didn’t ever know how to deal with having a child. Remember, he’s an early 20th century writer. He’s the kind of guy who probably thought, when he married Emma’s mother, that she takes care of the kids and I will earn a living. But of course, being a freelance writer, he was living entirely in his house. Emma, as a little girl, is constantly looking for attention from her father, and isn’t getting it. He’s really focused on his writing, and at the same time, perhaps he also sees it as this is how he makes a living to support his daughter. She’s not going to appreciate that at the age of four, the age of seven, it’s not until she's much older she might understand it, but even so, I think she’s come to a point in her life where any gesture he would make, even if it was the right one, is too little too late.

AM: Do you feel that Abraham is an unreliable narrator?

MAB: You know, that’s a very good question. I do not feel he is unreliable in the sense that the events of the story are true. I don’t think he’s going crazy, I think he really is in touch with the future. That said, I think he’s got his own perspective on the events of his life. I think if you were to sit down with him and ask him, why don’t you think you have a good relationship with your daughter, he would put more of the blame on her than on himself. He was doing all the right things, how come she has turned away from him? He isn’t necessarily able to step out and view it from her perspective, although he probably thinks he is.

AM: Yeah, he comes off as a little self-centered.

MAB: Yeah, he is self-centered. You know, as people get older, sometimes they become more set in their ways. They think, well, why can’t the world just be the way it was when I was younger? And I think that’s sort of the way he is. And there’s an irony here, a deliberate irony. Science fiction writers can sometimes be the most calcified, set-in-their-ways people imaginable. Not all of them, but you have the stories about writers who will still use their typewriter, and only their typewriter, into their later years. Abe wants to see the future be the way he envisioned it. And when it turns out to be very different, he wants to reject everyone and go into his own future.

AM: Science fiction in general has a low success rate when it comes to predicting the future. Do you think that affects the worth of those stories at all?

MAB: If the goal of science fiction were to accurately predict the future, it would not be science fiction, it would be futurism. At the same time, sometimes things get predicted in ways you wouldn’t necessarily expect. George Orwell, he predicted that the government would be looking over all of us. But nobody predicted that it was going to be mostly corporations, and nobody predicted we would hand over this information voluntarily and willingly, for the sake of certain conveniences. You have to keep in mind that it’s very easy for science fiction, or anyone, to predict certain changes in technology. But the trick is predicting the social consequences.

AM: The protagonists of the stories within the story seem to reflect Abraham. Do you feel Abraham reflects you in any way?

MAB: I’m going to let you in on a little secret that nobody knows yet. One of my good friends from high school is a writer/publisher named Charles Ardai. You may know him as the husband of Naomi Novik. Back when we were in high school, Charles wrote a coming-of-age novel. He did what you do, you take a lot of your friends and put them in the story. My middle name is Abraham, and at one point in high school, I grew a really big beard. So he named that character Abraham Beard, to be basically a version of me. And it was interesting, because he did capture aspects of me in that character. Later on, Charles occasionally would use the name Beard in a story to refer to some science fiction writer. So I used that character name that Charles came up with.

Now, that said, I’d like to think that I’m a nicer person than the character is. I think I can have a better relationship with my kids. But I definitely strongly identify with a lot of what he says. Look, the fact is, in 2011 we ended the American crewed space program. Every astronaut that we put on the International Space Station is going up in a Soyuz. Why aren’t we putting investment into trying to establish a permanent base on the moon? Why aren’t we trying to get people on Mars? Abraham, these are his concerns, and as a result he tends to dismiss technology. He sees people looking too much inward, rather than looking outward. I don’t reject that, but I do agree we should be doing more to explore. And a big part of that obsession is that every living creature that we know about is living on one planet. And that’s not a sustainable situation. I like the idea that something the equivalent to self-consciousness, intelligence, the human race, will continue to exist, and that is going to require getting off the planet.

AM: There’s one point in Fire and Ice where Sandra says, not only are we going to save ourselves, but more importantly, we’re going to continue remembering everybody who came before us.

MAB: Yeah. And this is one of my obsessions. She’s talking about how this universe is coming to an end, but they’re going to make sure that people remember, they bring it forward. It’s a classic concept, that if there are still people around who remember you, then in a way you’re not gone. And that’s sort of what I think about in that story. And the irony is that Emma, who is around, who will remember him, isn’t going to remember him in a positive way.

AM: Science fiction is literally Abraham’s method of escape from reality and particularly from mortality. Do you think that science fiction in general is useful as an escape from real life and from death?

MAB: I think for him it’s more of the idea of leaving the legacy. Again, it’s part of my own obsessions. And I think they fall into his mind as well, especially given that, in this particular story, he is at the end of his life. He is trying to figure out what kind of legacy he’s going to be able to leave for the future. Of course, someone who is writing mainstream fiction might be thinking about their legacy, about wanting to make sure what they write is remembered in the future, but the interesting thing about writing science fiction is you’re writing about that very future that you’re hoping you will be remembered in. And that does create a problem. Are these novels going to be remembered by people because they are so dated? The writer and critic James Nichol has a website called “Young People Read Old Science Fiction.” He got a bunch of younger people to read Asimov’s “Nightfall,” which twice was voted by the SFWA as the best science fiction story ever. And a lot of them just can’t get into it. They see flaws, they see issues. I love Asimov’s work, but I can see some of those flaws and issues, too. How is this going to be remembered?

§

Klayton Stainer

§

APEX MAGAZINE: How did you first encounter “I Remember the Future,” and what attracted you to it?

KLAYTON STAINER: My family and I head out together to our summer cottage every year after Christmas. I received a book called The Mammoth Book of Nebula Awards SF as a gift from my parents. Michael A. Burstein’s “I Remember the Future” featured in this book, and when I read the story it just grabbed me. I was immediately drawn to the characters and I felt myself storyboarding Michael’s brilliant writing—in my head—it was so clear almost as if I had already seen the completed film. That’s when I knew I had to make contact with the author.

One thing that really attracted me to the story was the different ‘worlds’ which the main character, Abe, disappeared to in his mind. I was intrigued at the possibility of essentially putting seven different short films into one longer piece. It of course also opened up the possibility to play with these different scenes each in their own way. Each ‘world’ has its own aesthetic characteristics—every character has its own background story, look, feel, and colour.

AM: How would you describe Abraham? What is the essence of him you want to get across? And what did you look for in an actor when casting the part?

KS: Casting someone for the role was a challenging thing. The actor needed to be someone we could all relate to in a way, someone you would feel sympathetic toward, but also not sorry for. I always had a vision of what the character should look and sound like. When I met Reg Gorman, suddenly all the pages of the story made sense. Reg is also a very strong actor, his expressions could tell the audience a story without speaking. This was essential for Abe’s character as he drifted in and out of reality.

Abe’s dreams and hopes very much represent the everyday person. Everybody has a dream they wish to come true. We wanted to get across most of all how Abe dedicated and lived his life through writing about a future he dreamed of.

AM: How about Emma?

KS: Emma is a character who had to fend for herself in an emotional way since she was young. Her father was lost in his writing and didn’t tend to the reality of her life. Of course, she grew up and I suppose loosened herself from his fictional world he was living in. Her relationship with her dad is estranged and I think her only salvation is his death.

I looked for an actor who could portray Emma’s assertive personality. And we were very lucky to have Tiffany Lyndall-Knight play the character. She really brought a sense of longing for a dad, along with the backstory of never being able to truly experience what it would be like to have one.

AM: The same actress plays both Emma, Abraham’s daughter, and Sandra, one of his characters. What inspired that choice? What is the connection between these two women?

KS: We decided to have the same actor play Sandra McAllister, to show that although Abe was an absent father, his world (which was his work) did in fact revolve around his daughter. She was the inspiration to his stories. Sandra was one of his favourite characters in his books and most certainly a leading lady. By having Tiffany play both Emma and Sandra, we created a link between the two characters that represents Emma in the way Abe has always seen her: strong, independent, and a woman who he believed could lead a revolution.

AM: Why do you think Abraham has such a strained relationship with his daughter?

KS: I think Abe never really got to know his daughter. We gave Emma the backstory of a young girl who saw her dad as a hero—writing all of these fictional stories. One day she grew up and realised that she could not live in a fictional world. She feels as though her dad’s whole life passed him by and I think the fact that her two sons cannot have a ‘real’ relationship with their grandfather places strain on Emma and Abe’s relationship. Abe has a second chance to be to Zachary and Kenneth what he never was to her. But of course, as we know, Abe never changed his ways.

AM: Do you feel that Abraham is an unreliable narrator?

KS: I don’t think Abe is an unreliable narrator. In fact I think that he is the only character who can truly explain to the audience what is going on in any given moment. When we meet Abe he is living two lives, so to speak. He may be losing his thoughts and ideas in reality, but in a fictional world anything is possible and the idea of sickness or in his case dementia can be erased from any character by simply removing a page from the story.

AM: You can tell a lot about Abraham by looking at his surroundings. What do you want the audience to notice?

KS: His surroundings are essentially his mind. A million different things and ideas scattered on top of each other. We aimed to get the idea across of someone who does not care about ‘mess’. Abe truly believed that there is something bigger and better—a vast universe of technology and at some point the human race would have to leave earth behind. So when this day would come he would not think twice about the state in which he leaves his house.

AM: Are the heroes in Abraham’s mental flashbacks different versions of him?

KS: We wanted to aim toward Emma being the inspiration for all of Abe’s stories and in almost every flashback we find a strong female or mysterious character. The idea of having Abe place his daughter on a pedestal in this way eases the audiences’ mind about Abe being a better father-figure than what Emma realises. So in many ways we wanted Abe to be a father to his stories, a ‘creator of worlds’. This is portrayed in the conversation he has with Sandra in the final scene.

AM: We see Abraham reading The Number of the Beast by Robert Heinlein. What’s the significance of that?

KS: This is a personal input from me. The Number of the Beast is one of my dad’s favourite science fiction books. And since I received The Mammoth Book of Nebula Awards from my parents as a Christmas gift, which gave me the idea to make this film in the first place, this was my way of saying ‘thanks’. It is also a little Easter egg for scifi lovers as the story is about dimensions and fictional universes.

AM: I won’t spoil the ending for our readers, but I will say that you manage to maintain ambiguity by not showing us what Emma sees. Do you think what happens to Abraham, as he perceives it, is real?

KS: I’d like to think that what Abe perceives is real, otherwise what is the point? As an audience member I would like to see the character move on to something bigger and better—or moreover for his dreams to come true. But then again is that the reality of life? It certainly is not the way Emma could fathom the end of her father. So perhaps the story ends with Emma being faced with reality.

AM: There’s some irony to Abraham’s story winding up on the internet, in e-books, and now in the form of a movie that can also be found and watched on the internet. What would Abraham think of all this?

KS: I think it would not have been “good enough” for him. He would have been more satisfied if his story could be the first film screened in space—which is still be a possibility …

Check out the trailer for I Remember the Future: https://youtu.be/oZZGUs-K1GI