Not to be a stranger let me first introduce myself. I am Zohair, a Pakistani living in the melting pot metropolis of Karachi; I am a 40-plus recluse (of a sort) and I edit other people’s works for a living when I am not writing myself. For what it’s worth I have been writing since the age of 7, and I had written over 2,000 pages of first drafts and notes before destroying all of them when my mother died in 2019. I was still unpublished at the time.

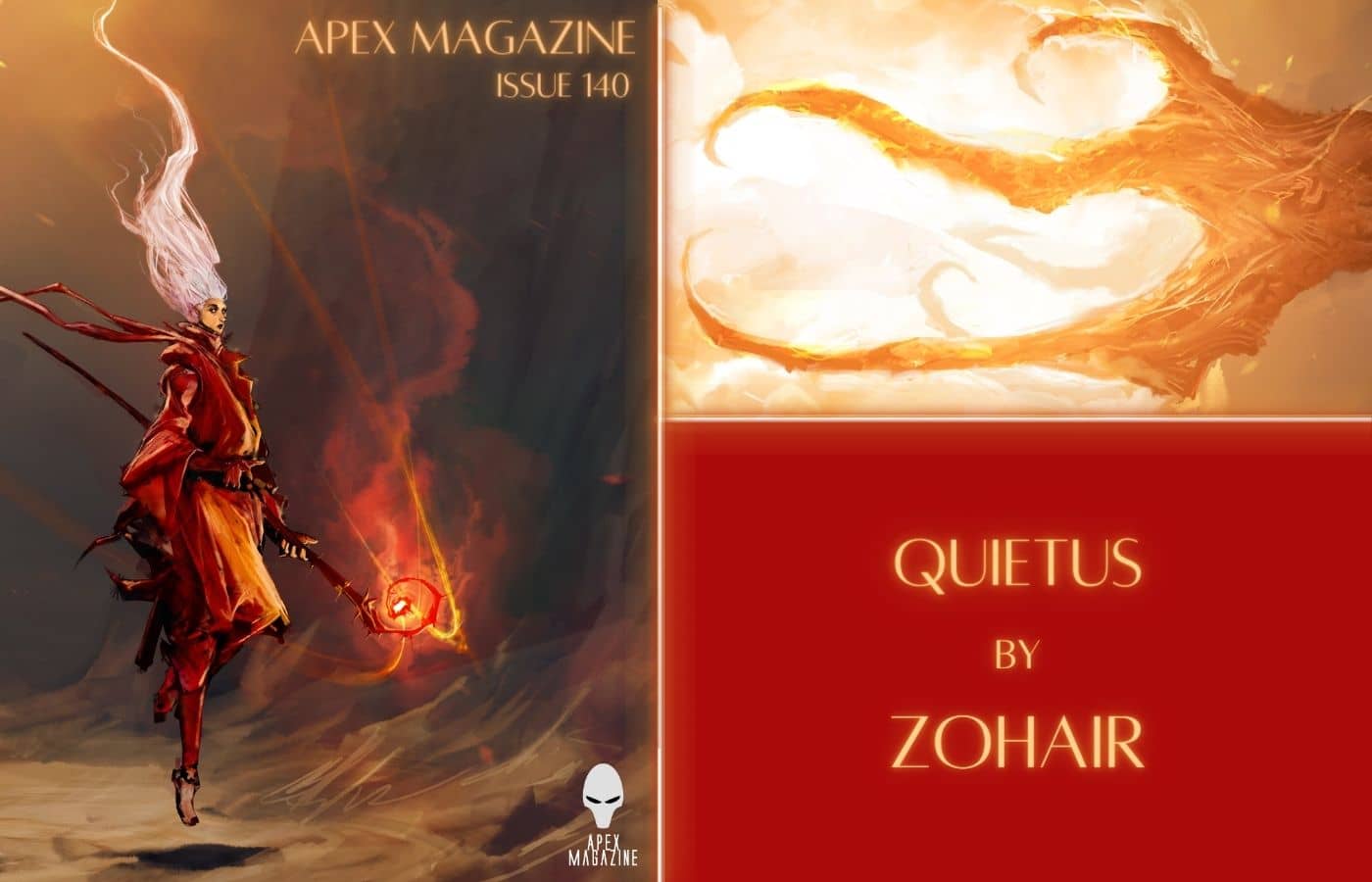

I am now the author of “Quietus”, published in Apex Magazine issue 140.

“Quietus” came out in September 2023, and since then I don't know of a single friend, family member, acquaintance, or anyone on my mailing list who has read it. And my mailing list contains over 220 names. Certainly, yes, they all congratulated me, but that wouldn't make them read the actual words.

I wasn't surprised, for finding readers in Pakistan is as difficult as finding writers. Speaking from my own experience, neither has anyone ever discussed a book with me, nor have I ever met a single fiction writer—the works I edit are only academics and columnists.

For a person who has never been to a theater, cinema, or a library—for that matter I have been to a restaurant only once—I might not be the best authority to divulge deeply into the mystery of scarcity of both the readers and writers in Pakistan, but I will attempt to carry, and do so confidently, a few points about the state of the literary scene in Pakistan.

Labeled the dinosaurs of Pakistani culture, writers have never been a popular breed of artists, and the case of their cultural scarcity has only been exacerbated by the lack of publishers, almost all of which require the writers to bear the publishing costs themselves.

Historically, Pakistani writers have a lineage of being persecuted for obscenity, blasphemy, or sedition from the very start, a trend beginning with a 1950s crackdown that led to the incarceration of some of the most prominent writers of the time and forced other important names to flee the country. This antagonism towards writers stemmed from a failed coup in 1951 in which the key participants/conspirators were some of Pakistan’s rising literary figures hoping to overthrow the government; understand, that same year the first Prime Minister of Pakistan was assassinated and the country was only four years old at the time. After that the authorities—mostly military—kept a check on the country’s writers.

Presently, for a general picture, long-form writers in English are only expatriates—maybe a dozen; poets come out to just over a hundred, and short-form writers are probably half that number. Playwrights are so rare that you can count them on the fingers of one hand (then the theatre troupes on the other) and none of them create exclusively in English.

This might seem strange for a country with a 200 million plus population. However, in Pakistan there are over fifty different languages spoken by people of as many ethnicities. In fact, my mother spoke six different languages and understood another three, and the neighborhood in which I have been living for the past thirty-nine years, I encounter ten different languages on a daily basis.

To foster any reading culture, language is always the key element. But in Pakistan the concept is rendered ambiguous by a political system in which each political party claims to represent a certain ethnic group, thus putting a claim on its language as well. Even the national language of Pakistan, Urdu, is claimed by a certain political party. And it was this very politicization of languages that led to the amputation of East Pakistan from West Pakistan to make Bangladesh, where the bone of contention between the two wings of the same country was its language: Bengali.

The obscure nature of languages in Pakistan can best be illustrated by an incident that occurred while I was writing this essay: it happened in Lahore, the second largest city of Pakistan, where a girl was almost lynched by a mob for wearing a shirt with an Arabic inscription. Though no one really speaks Arabic in Pakistan, Arabic is held in sacred esteem and is often referred to as the language of Islam. Thus, the shirt’s Arabic inscription was equivalent—to the mob—to blasphemy. In Pakistan blasphemy is still punishable by death (according to law), and it doesn't take long for protesting mobs to turn into their uglier versions.

Yes, people here are willing to kill for a language that doesn't even belong to them. Were we to seek villainy, it would all come down to our education and sentiments—and more so on who gets to control them.

In less than a decade, a singer, who sang about angels and heaven, was accused of blasphemy and had to flee the country; a film attacking authorities in Pakistan was banned and the director had to flee the country and now drives a truck in another part of the world for a living. And in 2011, a politician who opposed the blasphemy law was assassinated by his own bodyguard.

It wasn't always like this.

Pakistan used to be more like the Turkey of today before the late 1970s military coup; a decade-long operation that used brute force to enforce its introduction of radical Islamic laws pertaining to the rights of the citizens (i.e. a rape victim could be jailed for being raped while the rapist could remain unpunished and free), quickly followed by a brutal attack on freedom of speech and free expression. At the time, government watchdogs for all fields of artistic expression were instituted. Even today no stage play can be performed until and unless it is officially approved.

I was born in the 1980s under that same brutal dictatorship. I was still a kid in school when it was eventually deposed. I remember, however, a lot of things from the time, like: there was only one television channel (transmission lasted only seven hours a day); there were VHS stores on every street; and I knew about private weekend parties where standup comedians and singers entertained guests on both sides of a lavish dinner; and we also had stereos and audiocassettes. These were the avenues for entertainment and leisure for Pakistanis.

But what I remember the most are the bookshops, some of which were bigger than the largest supermarkets of the time. We even had entire streets dedicated to books during that time. My favorite haunts were the thrift booksellers cramped within the wholesale fresh produce stalls at the weekend bazaar—a makeshift affair of tented stalls with over 500 hundred crudely assembled tables on a parched and sandy surface. It was a time of, if not unbridled creative freedom, wide and enthusiastic access.

However, all that disappeared come the 1990s. I can blame some of this on changing times, but we can’t ignore the fact that the deposed dictatorship had left behind a brutal legacy with a weaponized brand of religion. Right in front of me, traditional bookshops were replaced by Islamic bookshops that dealt exclusively in Islamic literature—but not Pakistani literature. There used to be five bookshops in the early 2000s in my neighborhood—the regular ones that sold, then very popular, Sidney Sheldons and John Grishams; now there is only one, but six Islamic bookstores have emerged selling solely books to further Islamic thought and word.

‘You are not supposed to start anything new in Muharram (the first month in the Islamic calendar).’ That is what my father always told me. ‘It would turn out bad.’ ‘It would only hurt you.’ ‘It is bad luck.’ Call it fear, superstition, or just caution, but those teachings have always been a lingering thought at the back of my mind; even now, when it's been over twenty years since my father's death, try as much as I want to I am unable to do anything in and around that month, let alone starting something new. It makes me feel crushed.

My father was a peaceful yet gullible man, but never really a fanatic, and not always given to sermonizing, even though most of the stories he told me were about Prophets, dead generals, equally dead politicians, more prophets, and some sportsmen.

My mother, on the other hand, used to tell stories of her family, Gurkha ghosts, brides with scorpions in their anklets, and dogfights during a war.

But neither of them ever talked about themselves. It is uncommon for Pakistani parents to talk about themselves.

We all know that the things we see, hear, experience, and learn in our childhood, are the seeds to the roots of our imagination, and I have always believed that the tradition of oral storytelling fosters all that as a necessary predecessor to written word. And by tradition, like in some other societies, here too it is the grandparents who carry this tradition of oral storytelling. But even here, we find constraints. In Pakistan the oral stories are restricted to Islamic stories; no superhuman or fantastical creatures, but Prophets. Prophets are supposed to be the protagonists of such stories. And no one is allowed to bend the narrative to their imagination—a thing a child feels utterly compelled to do!

And to handicap the art of oral stories further, here in Pakistan we neither have any fireside ghost stories nor any bedtime fairy tales, and worst still there is no tradition of teachers reading to children either. Most of us, like the ones who grew up in the 1980s and ‘90s borrowed our imagination mostly from the American and British science fiction shows that found their way to Pakistani television via syndication; even today the rejects of American television like Manimal, Automan, and The Wizard, are classics to those Pakistanis who grew up in the 1990s—I myself loved Twilight Zone, Star Trek, Tripods, V, and Land of the Giants. Yes, television was a medium meant to cultivate a child's imagination, same as what the internet can do today.

Poverty of written and oral stories can be compensated by myths, legends, fables, and folklore which is passed on from generation to generation, however, since Pakistani culture is multi-ethnic, there is no one shared mythology or legend; like their own separate cultures and languages, each ethnic group nurtures their own legends and folk stories, but nothing that could be branded as common to all Pakistanis. These folk tales are very few and sporadic and all of them sans any element of fantasy, and surprisingly (interestingly? Tellingly? Ironically and more!) all of them are about star-crossed lovers—and to me they all seem to be a variation of Romeo and Juliet. Fables (Qissas), thanks to Musharaff Ali Farooqi, belong to connoisseurs only.

Coming to written word and books, I have not yet met a single soul with an ambition or interest to write; I have seen a little poem here and there but nothing significant. ‘There is not enough money in it,’ is one thing everyone tells you. And by everyone I mean the publishers who are reluctant to invest in books, friends and families who tell the potential writers that writing has no future, and even the people who buy books! And there is no guild or literary authority that could cultivate talents of aspiring authors.

I told you what my father used to tell me, but there is one other thing that I was told often, and that was by my father’s best friend, which was more of a warning then a sermon: “If you want to be a writer then you must remember that you are a Muslim first and Zohair afterwards, and you are never supposed to betray the first; it would hurt your father, family, and people.”

And coming to friends, my name, being a Muslim and other people’s displeasure, I can’t help but mention that a couple of my own friends are not happy with the name I have used when publishing “Quietus,” Zohair, which is actually my first name and the one I am called by, and it is a very rare name itself even here in Pakistan. But actually there are four more different names (amounting to 19 extra letters) attached to my name, all of them (I don't know why) are there to identify me as a Muslim, none are my father or mother's name, nor my grandparents’ names, the other four are just there to cement my identity as a Muslim.

Fear of losing identity? Fear of losing religion? Is this what drives us to lock things away in tight compartments?

Call it paranoia or anxiety, but every country's got their own fears and maybe this is Pakistan's: losing something that it holds so precious and dear. But collective fear will always lead to hysteria, which is only a step away from madness and no one needs to look deep into history for examples of such trepidation; just go back to Rod Serling's ”The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street,” where a people, driven by their cankerous superstitions, imagination, and collective anxieties, throw themselves into a pit-hole of madness and despair. They create pariahs of themselves and their neighbors.

They cut themselves off from sources of light.

Every night when I go to sleep, I have a habit of tying a corner of the sheet covering me around my eyes, and I don't do it consciously; it just happens automatically somewhere in the night. Why? When I was a little boy, maybe eight years old, and when all the family had to sleep in the same room (to save expenses), a couple of thieves, after cutting through the window bars, came in and sprayed an aerosol to keep everyone asleep while they robbed us. The aerosol didn't work on me, but I lay there quietly pretending to sleep as they cleaned out the place, went out the front door, and locked us in; I was a helpless spectator to the scene. I am not afraid they will come back after 35 years, but it has become a habit to shield my eyes from what might come out of the dark. It would be hard to believe but I used to sleepwalk before that (once I even covered a block before an uncle caught up with me at 2 AM), a thing that was cured or maybe replaced with another—the shielding of my eyes—after the theft.

No writer is an exception to fear and insecurity, but what differentiates one writer from another is the environment they get to nurture their talent in; a country is supposed be a citadel to nourish that very talent rather than be a stockade where writers are treated as pagans and rebels. Me, personally: I have written and no one has read it. Are my words tethered to nothing? There is no sure conclusion to this essay I have written, but it is time that writers be freed from the shackles of censorship, and recognized as acceptable artists. And perhaps that would even bring in some good money, good plaudits, and good camaraderie to encourage others to pursue this art, for money is never a selfish demand for anyone who has invested time and toiled to craft an honorable piece.

Literature—life—is borne of longing, wanting, and reaching—traits different to each writer and, hence, making each written piece an individual experience. My “Quietus” was my individual experience. For my next experience I will go back to a Christmas play that I have been trying to finish for the past 16 years and the one about which a friend once said, ‘It would be a sin for a Muslim to write a Christmas story.’ There are already an untold number of sins.

Then why not another?