The first time I walked into a comic book store, I was eight years old. The town I lived in at the time didn’t have a local comic book shop, so the only way I could purchase comics was at the local grocery store, gas station, or convenient store, which meant that the selection was always limited. That all changed when my mother took me to a shop two towns over. There, I discovered worlds and universes, heroes and villains that would become a permanent part of my life.

This was also the first time that someone of my complexion appeared on the front of a comic (although mildly disguised). The comic was Iron Man, issue #170, from Marvel. In that issue, James Rhodes, a black man and good friend of Tony Stark, takes over the mantle of the armored superhero. This was the first time I realized what representation for black people in comics meant.

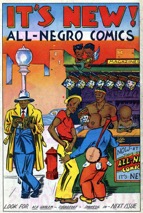

As I was taking the Iron Man comic to the counter to purchase, I saw a massive wall of well-sealed, expensive comics from the 40s, 50s, and 60s. What I didn’t know then was that one of the comics on that wall was the first attempt to give full representation to black people in comic publishing. The cover of the issue was a hodgepodge of black characters, but the top of the front cover was torn, so I had no idea what the comic was titled. The price tag on it was too expensive for my eight-year-old budget, so it became an afterthought.

Years later, I learned more about the comic book on the wall with the torn cover. In 1947, a man had a vision and goal to change the face of comic book publishing. He also wanted to give black readers the opportunity to see themselves on the page during a time before the civil rights movement and to provide the possibility to imagine and realize that they, too, had the right and ability to create stories of all kinds in a country that didn’t see black people as equals.

That man’s name was Orrin C. Evans, and the comic that he wrote and published was called All-Negro Comics.

Before Evans made the foray into comics, he began his career as a journalist at the age of seventeen and ended up working for the black-owned Philadelphia Tribune. Years later, he became the first black writer for the white newspaper known as the Philadelphia Record, working there until the end of World War II.

When his job as a journalist came to an end at the Philadelphia Record, due to the upper brass wanting to close the newspaper down instead of dealing with an employee strike, Evans decided to make a career shift. An avid lover of art and cartoons, he decided to create his own comic book series instead of journal writing and articles. He would tackle issues that black people dealt with in America while giving heroic images and actions, and also reaching a wider audience that may not have been aware of his writings for independent papers and magazines, such as the NAACP. He didn’t want to do a comic that would only be syndicated in a few black newspapers; he wanted to make comic books that would be distributed in as many outlets as possible.

To create All-Negro Comics, Evans would need to bring together a host of talented black writers and creators for the debut issue. These included Harry Saylor and Bill Driscoll (former editors at the Philadelphia Record) as publishers. Evans served as President of All-Negro Comics, Inc. and created and wrote a majority of the featured characters presented in the anthology-style comic book.

When All-Negro Comics #1 made its debut in the summer of 1947, it was the first comic ever to be exclusively written and drawn by black creators, filled with stories featuring black characters. The issue also made history as Orrin Evans became the first black publisher in the comic book industry.

The “superstars” of All-Negro Comics #1 were private detective Ace Harlem (drawn by artist John Terrell) and the action-packed Lion Man and Bubba (with the artwork of George J. Evans, Jr., the brother of Orrin Evans), featuring a well-educated scientist that ends up on a mission in Africa’s Gold Coast.

Stories in the first issue include the cherub-esque “Little Dew Dillies,” the joke/gag-filled “Hep Chicks on Parade,” the husband and wife follies of “Lil’ Eggie,” the musical journeys of “Sugarfoot and Snake Oil,” a short text-based story called “Ezekiel’s Manhunt,” and a one-page PSA reminding kids that “crime doesn’t pay.”

According to writer Tom Christopher’s history of All-Negro Comics #1 from an issue of Comic Buyer’s Guide, “No information about the press run or distribution remains, but it is believed that the comic was distributed outside of the Philadelphia area.”1

With the success of the first issue, it was certain more issues of this anthology series would be published. Unfortunately, that did not happen. The accolades and sales could not withstand the racial and segregated climate of the time, and the company that printed the first issue wouldn’t handle the second issue, and Orrin failed to secure a different printer due to the area’s racial temperament. All-Negro Comics died after only one issue.

After All-Negro Comics, Inc. came to an abrupt end, Orrin Evans returned to the world of journalism and newspapers in Philadelphia, doing editorial work, and later he became the director of the Philadelphia Press Association. Orrin Evans never stepped into the world of comics again.

In today’s world, the comic book business has become more inclusive on the page, but it still lacks any meaningful representation behind the scenes. There are few writers of color for the major comic publishers and a lack of opportunities for people of color to be in key positions that can make the decisions to shape the future of the business. In 2016, Marvel hired award-winning creator, artist, and animator Nilah Magruder to write a digital exclusive comic book for the company, A Year of Marvels: September Infinite Comic #1. She was the first black woman in Marvel’s 77-year history to ever write a comic for the company, but the company never publicly stated it. In November of 2017, DC Comics announced “The New Age of DC Heroes,”2 featuring inclusive superheroes and teams, but no black writers, writers of color, or women creators.

There’s also the issue of false correlation, where some will say that making comic book characters more inclusive on the page has caused a downward surge in sales. In an interview with ICv2 in March of 2017, David Gabriel, who serves as Marvel’s vice president of sales, decided to blame their sales slump on diverse and female characters that were being published by the company. “We saw the sales of any character that was diverse, any character that was new, our female characters, anything that was not a core Marvel character, people were turning their nose up against. That was difficult for us because we had a lot of fresh, new exciting ideas that we were trying to get out and nothing new really worked.”3 That statement was later contradicted in a Fortune article featuring then Marvel editor-in-chief Axel Alonso which said that “the rush to diversify characters has more to do with business than politics, in Alonso’s telling”4 and that the success that the company was currently having was due to promoting diverse characters. Gabriel later walked back his statement.

Even though Evans was stopped from completing his dream, there are creators today who are paving their way in a business that suffers from a severe lack of change and issues of gatekeeping. C. Spike Trotman has crowdfunded over one million dollars worth of successful Kickstarter publishing projects with her Iron Circus Comics label, which publishes diverse sex-positive and erotic comics, as well as never-before collected popular webcomics, such as Sophie Campbell’s Shadoweyes and TJ and Amal, that serve an audience that is looking for more than just capes and tights. Ngozi Ukazu created Check Please, which is one of the most popular webcomics around, and is based on a fictional collegiate hockey team. Tee Franklin went from writing about comics and putting a spotlight on creators of color with her #BlackComicsMonth panels, to writing and crowdfunding the successful Bingo Love, which has since been picked up by Image Comics. Anthony Piper created the viral sensation superhero team known as the Trill League, who are hilarious analogues of the Justice League of America. Vince White wanted to see more superheroes of color, so he created The Powerverse with heroes such as Will Power, Purge, and many others. In 2015, I wanted to see more all-ages comics that featured black youth and kids of color, so I created the youth detective series Cash & Carrie. And there are countless others creating fantastic projects to a hungry and underserved audience.

I still wonder how the comic book business and landscape would look today for black creatives if Orrin Evans fulfilled his full mission. But no matter what, the push to get our dreams out there continues, regardless of the obstacles.

1 Christopher, Tom “Orrin C Evans and the Story of All Negro Comics.” Last modified 2014. https://www.tomchristopher.com/comics3/orrin-c-evans-and-the-story-of-all-negro-comics/

2 Battistelli, Ben/DC Comics “The New Age of DC Heroes.” November 29th, 2017. https://www.dccomics.com/blog/2017/11/29/the-new-age-of-dc-heroes

3 Griepp, Milton/ICv2 “Marvel’s David Gabriel On The 2016 Market Shift.” March 31, 2017. https://icv2.com/articles/news/view/37152/marvels-david-gabriel-2016-market-shift

4 Hackett, Robert/Fortune “Meet the Myth Master Reinventing Marvel Comics.” March 31, 2017. https://fortune.com/2017/03/31/marvel-comics-axel-alonso/