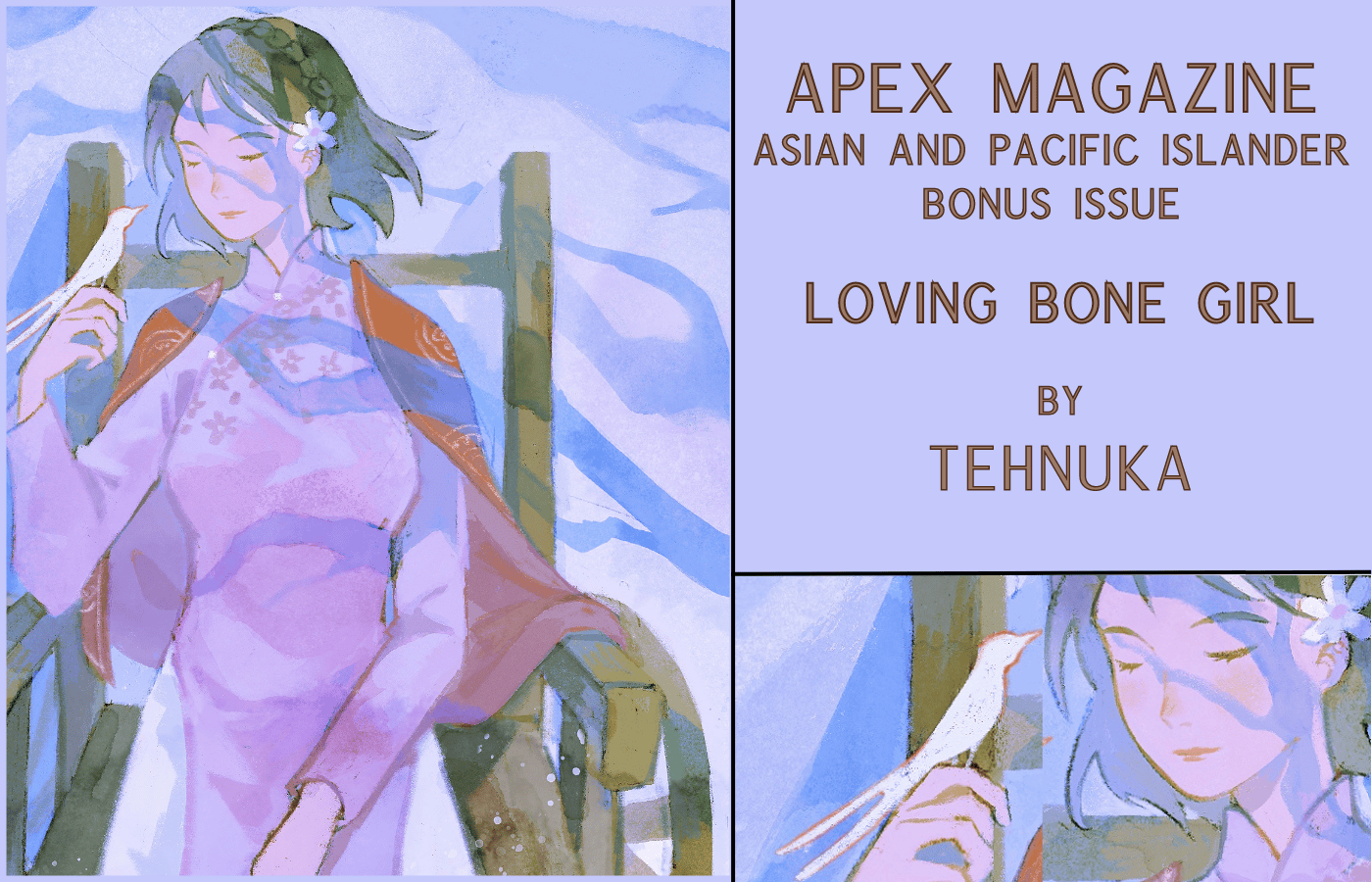

“When I die, I want you to keep my bones.” Vasanthi floats in the dark pool, the softness of her voice punctuated by softer drops of water from stalactites.

“You mean your ashes.” The best misunderstandings come from our language differences. “I’ll find you a nice urn.” Something brushes my ankle and I flinch away, peering back to where golden lantern light shows a small white fish drifting in the murk.

Water drips from Vasanthi’s face where I’ve splashed her. Her hair swirls in the ripples, black on black, but her eyes gleam. “No. I mean my bones.” She switches languages, to leave no doubt. “My elumbukal.”

Ours has been a year-long love of windswept mountains and hidden meadows, of bright seasides, jungles, and limestone caves in ancient coral reefs, of all the places she makes. The gifts we exchange are old film songs, home-cooked food, and flowers—I am wearing a string of hers now. This, though, is talk for a graveyard or a burning ground at night.

I pull myself onto slick rocks grimy with bat guano. “Why are you suddenly worried about all that?”

To a blind fish swimming through long-dead-and-buried coral, perhaps this isn’t so unlike a graveyard.

Vasanthi stays in the water. “I want to know if you’ll care. You think you like my world, but I have to know if that’s true.”

“I do.”

How could I not? She waited for me when I didn’t know what I wanted, saying, “I only want you to be happy, whether that’s with or without me.” She gave me all the space I needed while life unraveled, and stood beside me as I knotted it back together.

I met her too late to see her own unraveling, but I know she is still painstakingly rediscovering snapped threads of her past and turning them over, wondering what she might create from them.

“Your world is my world too,” I add, though I should say, “Your worlds.” Her many worlds. She makes places out of other places, and takes me to them, and there I’m more alive than I ever feel with my family. My parents and their friends remember a home where they belonged, but for me, before Vasanthi, the closest thing to home was a country where you could never fit in but at least you would not be killed for speaking your own language.

“Mmhm.” Regardless of whether she’s upset or unconvinced, her face never exudes anything but love. She knows there is safety in sculpting her expression that way. To truly know what she wants, it’s her words you have to listen to. “I’ll show you.”

I am fortunate that my parents thought to leave their homeland before they even conceived me. Hers did not. But Vasanthi makes places out of other places, and that’s how she escaped a war.

Neither of us has been to this cave before but when she dives, knowing what she can do, I pause only to leave my flimsy towel and, shivering, return to the pool, follow her through a passageway in the wall of the subterranean lake. We hold our breaths for several seconds. It is, perhaps, the length of time between hearing an aircraft before the earth shakes, the ground hollows, and you feel the force of trees and houses and people flung outwards as irreparable debris.

She creates this place as she glides ahead, both hands cleaving through the water in slow strokes. In the extended pause between our breaths, warmth replaces liquid coolness and a shadowy hint of new rock emerges. It lightens as the short tunnel leads us into another vast chamber. The air is balmy, there’s a skylight far above, and she is glowing.

“Here.” She steps out in sodden hiking pants and singlet, wringing and plaiting her wet hair. I don’t look back at the shimmer of the blue water, or up at the limestone chandeliers, but squelch after her in my waterlogged boots. We skirt a shallow pit of round, perfect, cave pearls. The air smells cleaner, almost fresh, like an ocean outside. A breeze dries our skin.

“You always make such beautiful places,” I say in a whisper that won’t refract off the high walls. Even the bat guano only matters in a good way when I’m with her.

She waits in a space between two pillars, sitting on the rounded stump of a stalagmite. It has far to grow before it merges with its counterpart above into a column spanning the height of the cave like the others have. Her braid and mine both echo the drip-drip from the roof. Despite the swim, the string of orange marigold blossoms she gave me this morning remains wrapped heavily around my hair.

When I round the pillar, I see that she is holding a human skull in her left palm. It’s off-white, with thin lines spiderwebbing across and ominous sockets far blacker than our dim surroundings can account for. Behind her are several others, each nesting on piles of long bones and curved ones. A lone jawbone and a few detached teeth lurk between them, among traces of wet sand that don’t belong here, smeared over the limestone.

“I wanted to show you.”

Where I would ordinarily meet her eyes to show that I’m listening and that I trust her, take her hand tightly when afraid, or lean against her shoulder in silent affection, I take a step back, looking into empty eye sockets, staying close to a column.

“This is Amma,” she says, stroking the top of the skull. Her smile is her same-as-always smile that makes everything shine. The skull seems to be matching it, though I can’t be certain, without the rest of the head.

“It’s nice to meet her.” I’m not certain of this, either.

In the early days after Vasanthi and I met, when we were both too nervous to be entirely honest, she was the one who said, “Do you think we feel the same way about each other?” and then, “It doesn’t matter if nothing comes of it. I’ll always think you’re wonderful.”

It would have mattered, but it was the kindest thing to say.

So now, I say, “Mikka makizhchchi, Amma,” expressing joy at meeting her mother, because I want it to be joyous, for her sake. Because I don’t want her to ever doubt that I’ll always think she is wonderful too, whatever strangeness she surprises me with.

“My ammamma and ammappa.” She indicates, with an elbow, the two overlapping mounds of bones closest to the skull-less one that must be the rest of her amma. “That’s my chinnamma over there.”

My knees creak as I stand there. “Do they find comfort in being next to each other?”

Vasanthi cradles her amma’s skull and stares at me, still smiling, but her eyebrows have gone crooked.

“You know, rather than being burnt or buried, or their ashes scattered in different places.”

“Isai,” she says. “They’re dead.”

I’m trying. “Right, are they like ghosts?”

“Oh.” She puts her amma down and strokes one of the larger bones. Maybe a femur? I don’t want to look hard enough to figure it out. I wouldn’t be able to tell anyway.

Standing, she turns in a circle, studying the piles. “I don’t know. I don’t know what a pei would do, or if it would follow its bones around. Do you think their peikal would seem like they did when they were alive? Because I haven’t seen or heard anything of them, not since they died.” She sighs, and she’s not smiling anymore. Sometimes, only around me, she does forget her smile. “Only in my memories.”

“Well … what if you can make their peikal appear like whatever you want?” She makes places. Why couldn’t she make ghosts?

“They wouldn’t approve of us, however they appeared,” she says.

I first saw her on the beach a year ago, bare feet in gray sand and seashells, lost among a crowd of picnickers whose eyes she never met.

“Pavam,” they murmured. “Family gone in the war. Isai, she looks around your age. Go and talk to her.”

I didn’t know what to say. Everyone was watching, so I went over. “Vanakkam. I’m Isai.”

“I was thinking about leaving,” she replied. “I make places out of other places. Will you come?” And she led the way between rockpools, stepping carefully with her sandals dangling from her ring finger. Her nails were plain and ragged. Mine were crimson with nail polish from a dance performance the day before. We stopped to laugh at hermit crabs and marvel at camouflaged fish and the snail whose colors reminded her of green parrots with red neck-rings. When we rounded a corner of the cliff, we were at the bus depot in town. She paused to slip on her sandals. Confused as to how we had covered several kilometers in a few steps, I began texting someone at the picnic to explain we’d decided to head home, but when I went to check the electronic timetable for the 26, it was blank. The people walking around were blank, too. The buses waited empty at their stops with engines off and doors closed.

“It’s never the same places,” she mused. “But that’s okay. It shouldn’t be the same places.”

I didn’t worry that I couldn’t make sense of it. Not because she was smiling, because she smiled at everyone, but because we looked into each other’s eyes. We sat outside on cold metal seats with curved backs. She told me her name was Vasanthi, and about what she’d seen on her journey through jungles and mountains and dense cities. She’d crossed oceans through the places she made to get here, although she hadn’t been at the seaside from the time she fled home until today. She didn’t talk about the war and how it ended, trapped against the sea, not then.

Next to her stories, my life was insubstantial. I told her about the bridegroom parade my parents kept putting on, the classes I taught and the children who shone, and how I’d love to see the places she made.

“Come with me again, next time,” she invited. We returned to the beach, where the rockpools were submerged and I rescued my backpack from the rising tide. From the seafront boulevard, we found separate buses into the city. This time, the people were real.

Vasanthi made places to escape to and was generous in offering them to me. After that day, she never left me behind. We spent Deepavali waiting to see fireworks on a bridge, crammed in amongst blank strangers. It was a bad idea. I must have learned to fear loud noises from Amma in the womb and she, at each explosion, gripped my hand back tighter. While the fireworks continued, she pushed through the crowd to a warm sunrise beside a splashing waterfall. We leaned against each other, seated on mossy rocks. I sang her songs Amma had heard on the radio in her childhood, making up the words I couldn’t remember, and Vasanthi told me about the black-and-white films they were from, that her mother had watched as a girl.

When the classroom demanded my attention, she waited in my world instead of escaping into hers. She came to visit my family, bringing oily laddu and under-ripe bananas tinged with green. I brought out too-strong bitter tea that she drank unhesitatingly, though my parents returned theirs to the tray.

Later, complaining that the laddu were too fatty but eating them nonetheless, they asked me to at least show a little interest in the boys they presented. I didn’t have the energy to decipher—let alone try to explain to them—what she meant to me. This life, my work, even my family, were dull and pale after the richness of time with her.

She didn’t mind that I hadn’t told them yet. “It would be exactly like this for me, if not for the war,” she said. “My family would have done the same, looking for a husband. Finding you has been the only good out of all this.”

When we were together, we shared moments of calm discovery in the places she created. She threaded me fragrant strings of bright flowers, like women wear in their hair, like we offer gods at temples, like garlands for weddings or funerals. “One day,” she whispered, “your family will understand, and I won’t need to make these sanctuaries. I wish you had been with me back then. You are the safest place I can imagine.”

“I am not sure if I came to the right place.” She turns her amma’s skull to face her and kisses its forehead. “To live, that is. I know the place we are in now is the right place to keep my family. They were mixed up in a pit with other people’s elumbukal before. If I knew I could move people, I would have brought them here alive and whole. But no one expected they would be dead in a pit until it was too late.”

Did she even have this ability to make new places when her family was alive? I suspect it is a more recent skill born of desperation, an involuntary exchange she would rather not have made. I don’t suggest that to her yet. All our people share the grief of being scrubbed from our land, blending into others to survive, of knowing there is nothing of ourselves we can leave behind there, or here. But although I watched the news wide-eyed for those last months of the war and wept every night in my bed thinking of dead people in bunkers and the world exploding, I will never truly understand what it was she escaped.

“I’ll keep your bones.” I wonder how one extracts bones from flesh. I don’t want to know. “I’ll keep your elumbukal if you want me to. But I won’t be able to bring them here to your family without you. You are the one who makes the places.” When I shrug, orange petals fall from my braid.

She nods. “I won’t need their bones after I die anyway.”

“How about you? Will you keep mine?”

“If you want me to.” She touches her amma’s skull one last time, settles it on the pile of bones, and passes back between the pillars down to the water’s edge. “Sometimes I don’t know if I make the right places.”

Sand grains crunch underfoot as I follow. “Do you want me to keep your bones somewhere else and visit, like you do?”

“No, Isai, keep them with you.”

“I don’t think we’ll need to worry about it any time soon.”

She walks waist-deep into the water and looks back at me. “You don’t have to worry. I’d like it if you didn’t.” Now she looks past me. “I worry. I worry about how they died, and that I don’t know how I got their bones back from a hole in the sand mixed full of other people’s families and shredded palm trees.”

She is trembling in her body and her voice, although the water is not cold. It ripples around her. “I worry about how I fled that place by making new places, and found you, and a life where we can be together. I worry that the places I make will fall apart without me when I finally leave. That I am creating something beautiful only to destroy it. I want something to last, someplace that is still safe, after I become …” she waves a hand towards the chamber of bones “… like them.”

As I wade in to join her, my boots heavier than before, the tiniest of doubts nudges into my mind. “I won’t fall apart without you.”

I’m not certain of this.

Behind us, the chamber fades. In a few steps, we will have to dive. My eyes meet those of her wavering reflection on the dappled pool. I take her hand, hold it as tight as my shaking fingers will allow, and rest my head on her shoulder. Another marigold detaches from my hair and plops into the water.