Because Waigong ran out of money due to the rice shortage, he gambled away my mother, an eighteen-year-old girl known for her beauty and dance prowess. She danced like a majestic water dragon, elegant and unstoppable while flowing through the atmosphere, limbs fluid like ribbons, and all the men would stare even though they claimed to dislike thin, pale women to their tan, rice-sowing wives. Waigong reasoned that losing was impossible since he had won all of his previous mahjong matches whether he used his lucky ivory and bone tiles or tiles etched from bamboo. No one in the city could defeat Waigong; not the son of Auntie Dong who memorized all the books at the local bookstore, not Mr. Lin who’d passed the imperial exams to work in the royal court. Further, most outsiders knew little about the city’s version of mahjong in which there existed a special Wind group composed of Dragons. This random outsider stood no chance.

Waigong sat across from the stranger whose heavy silk satchel rested on the table like a brick of gold. The stranger crossed his legs on the chair, smoked a cigarette, and asked for another cup of Maotai as though he owned the room. Waigong probably realized early on that he was going to lose even though it wasn’t clear to spectators. Something about the way the stranger carried himself—slightly slumped, but relatively motionless, like a relaxed king—unnerved Waigong to the point he could no longer think straight. Midway through the game, Waigong tried to back out from his bet, the fear of losing his daughter transforming from a joke into a tumor in his alcohol-ravaged gut, but the stranger refused and the game unraveled. My mother married the stranger and left the city despite Waigong’s insistence that he’d rather cut off his limbs, the cost of reneging on the bet. “No one needs to die over this,” she said.

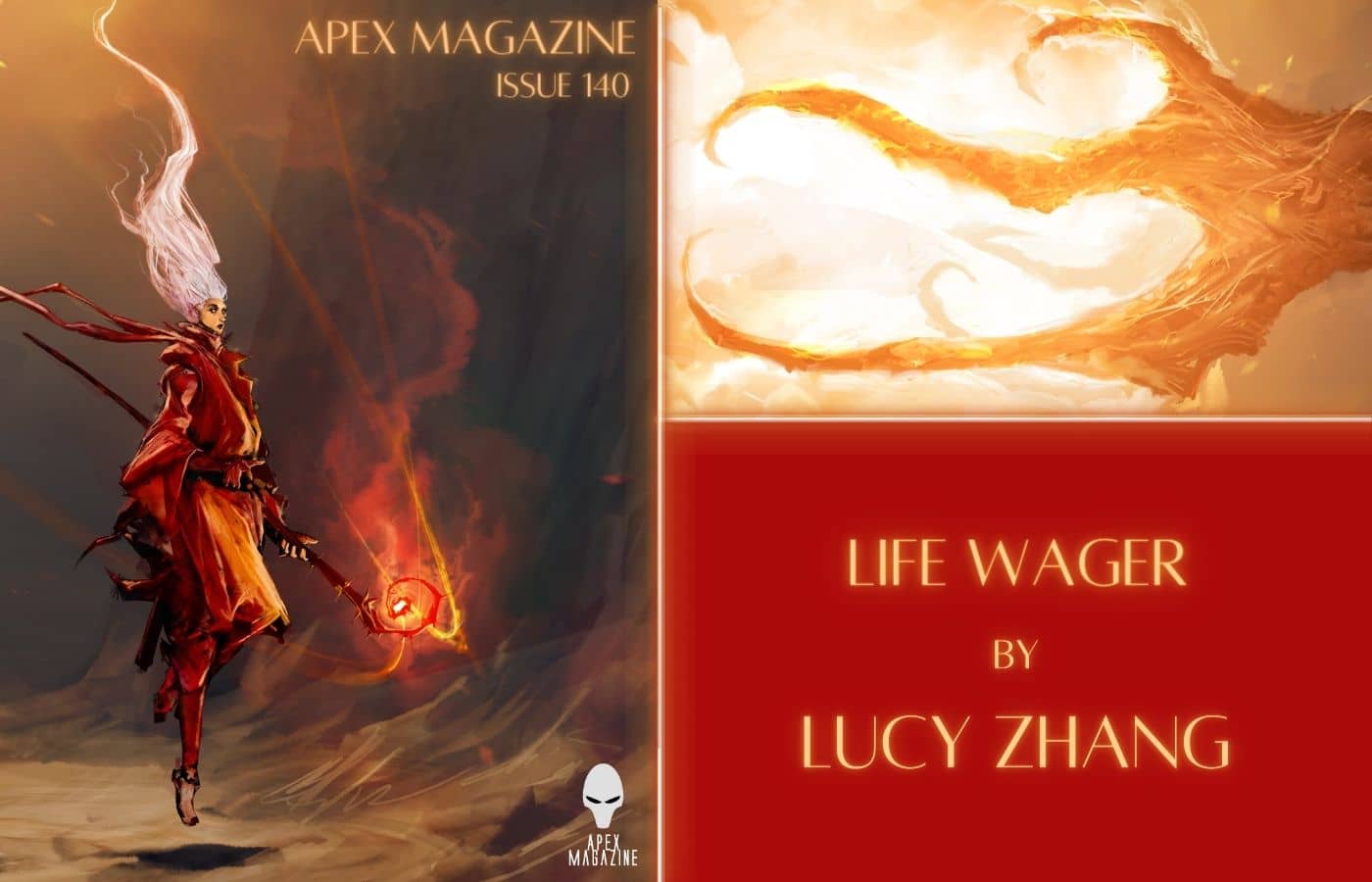

The stranger, my father, turned out to be a dragon. They gave birth to me in the sky well of a temple, an area that received the most sunlight and least exposure to cold north winds in all of the heavens. I’d rarely see my parents together. Father spent most of his time hovering above Earth casting typhoons and floods on regions, or light rains when he felt generous. Mother danced for the cosmic gods from morning to evening, and though she was not nearly as beautiful nor majestic as the Deities, they likely saw in her what the humans saw: a lightness yet heaviness in her leaps and spins, as though she might simultaneously fly away and drag you through the ground like a corpse. This was probably as close to the feeling of death as the Deities would ever get. It thrilled them.

I say this because even though I had lived all my life in the heavens, I left to the human world despite the protests of my mother who’d grown accustomed to performing for attention instead of money, who’d learned the luxury of eating Pinggu peaches and drinking loquat wine whenever she pleased, who needed only to smile and curtsy and occasionally twirl in front of a god to acquire their blessings for longevity or wealth, staving off the end of her comparably short human lifespan. Even my father, who rarely visited, protested my descent, arguing that I would not be able to handle the evil, deceitful nature of humans and that if it weren’t for him, Mother would have been lent out to travelers as a means of maintaining and focusing their “jing” which was a nicer way of saying she’d have become a sex toy. But neither of them cared enough to prevent me from leaving, and at that point, I had already made up my mind. I liked the thought that I’d yet to unearth a piece of my identity that Mother had rejected, a wealth of history that I was certain extended beyond arranging lotus flowers in my hair or grinding mother-of-pearls for immortality supplements.

The most noticeable difference between the human world and the heavens is the color. Clouds pave the heavens instead of streets, but here, dust and dirt lick my ankles with every step I take. Splotches of grays and blacks spot the ground, stains from wheels I presume, and no matter where I look, I fail to find anything that matches the same singular shade of white as I was accustomed to—not a single building, cheongsam, rabbit, white peach, or even mantou which appear more yellow and tan from the cheaper, less milled wheat flour than what we ate in the heavens.

After the tenth day of wandering, I witness two elderly couples discarding and snatching tiles, and then shuffling them like ice cubes. I eye a trio of Dragon tiles and for the first time, I find a white that nearly matches the shade from the clouds I remember. The couples play on the side of the main street, sitting by a table next to an untended chicken gizzard skewer stand. I hover around the stand underneath the shade watching them. They notice me only when one of the women lectures the men about “properly doing work” and not “goofing off with games” even though all of them have been shouting “peng” and “chi” over each other, devolving into an argument over who was fastest. One of the men stands to ask if I’d like a skewer, and I buy one out of courtesy for staring so long. I continue to visit for several days, watching them snatch tiles and flip them over and trying to associate similarly patterned tiles with one another. On the fifth day of my staring, they offer to teach me the rules since one of the women finally lost hold of her wits—an “incurable disease of the mind” they called it. One that worsens imperceptibly over time until it hits like a wave, like rotten durian that’s finally cracked, spilling flesh with the consistency of rotten egg and vinegar. “That’s what her brain probably looks like,” they tell me.

When I first join them in their games, they let me play without betting. But after a week and several win streaks, they demand I toss several coins into the betting pool. I’d earned money while in the heavens, grinding and selling pearl powder concoctions for immortality, though I’d never had a reason to use the coins because the blessings Mother received provided us with all the food and amenities we could ever need. I eagerly toss a coin into the pool. No one here is trying to make a fortune—the uncles and aunties are too old to do anything with money besides bulking up their children’s inheritance, and I’ve yet to find anything I want to buy with human currency. They claim that stakes make games fun. “You always need a goal as your anchor,” they advise me even though I’ve been around longer than them.

I win all the games.

“It’s because you’re young, your brain is sharp!” they say. “You can memorize all your winning combinations. You’ve probably deduced all of our hands, too. Actively sabotaging us!”

“There’s no such thing,” I say.

“We don’t even remember whether we were supposed to buy daikon or pork bones at the market.” They complain to me every day to the point I purposely lose several matches, but when I do so, they complain even more. “Now you’re making fools of us! Who are you to pity your wise elders?”

At this point, I fear they’ll go broke and offer to return their coins so they can at the very least continue to bet and play. They refuse and claim only fools throw money they’ve earned away, and bigger fools give it to those who’ve done nothing to earn it. “That’s how you breed stupidity. With nonsense like charity,” they condemn.

Despite their words, they eventually run out of money to bet, and they’re sensible enough not to tap into their savings for daily expenses.

“We’ll defeat you yet,” they promise. They bring sons and daughters of friends known for their quick wit or shrewd business decisions, and occasionally known for their sharp eye for mahjong. I play against these people match after match, and although I lose a few rounds at the beginning, I grow accustomed to their patterns and win the matches. “I’m just optimizing for all possibilities,” I say. This was what the old couples had taught me: to maximize the number of unblock tiles. That, and my opponents expose their habits too quickly: the one to my left picks up a discard within the first round and shouts “peng” with the speed of an eagle swooping for its prey, the one to my right never discards his tiles, the one across from me secretly groups her tiles so that it’s easy to see if she has a complete hand, but her finger motions are too wide and the light tap of the tile on the table too loud to go unnoticed. I know exactly which groupings she has yet to complete.

Local and regional mahjong champions challenge me. I continue to win. Eventually, the emperor, a young man who’d recently ascended the throne, sends a request for a match. The emperor is known to play mahjong with his political opponents and wager his life in bets, which, given he is still alive, he always wins and subsequently brings favorable conditions or trade relations to the country. He brings his military strategist and economic advisor as the other two players, along with his extended family as an audience, attracting citizens from the entire country to our little, dirty town without white. The town bustles to life that day, vendors setting up their street stalls hours earlier than normal, preparing triple the amount they’d normally sell in anticipation of the influx of visitors. They take down their old, cardboard signs and hire calligraphy artists to write their new signs on fabric, doubling the prices of trinkets and street food. The young girls paint origami butterflies and flowers folded from their notebooks, hoping to sell them as artisan, regionally exclusive beauty products. On the day of the competition, I wear a long silk dress patterned with gold flowers and embroidered sleeves provided by the local tailor, who dreams of making clothing for royalty. The emperor, his military strategist, his economic advisor, and I sit around a wood table, the same wood table at which I played against the elderly couples.

The emperor, as we’d all expected, wagers his life. In turn, the rest of us wager ours as well.

“It’s not a favorable situation for you,” the emperor warns. “The lives of my strategist and advisor are already mine. The only one that has something to lose is you.”

“You as well,” I reply.

I assume at the time my father is watching because it rains as though he is trying to hurl the heavens down to earth. We can hardly hear each other speak as the rain drops like stones onto the rooftop. The emperor goes first. He wins the first round, and says, “The nice thing is, no matter how skilled you are, you can still get lucky and win.” We continue for sixteen rounds, the only words from our mouths “peng” or “chi” or “gang”. The military strategist speaks with an extraordinary amount of passion, as though commanding us into a losing battle. I like listening to him enunciate, especially how I can hear the way his lips move from the air pressure. The economic advisor remains quiet, eying the tiles and periodically glancing at the discard pile as though refreshing his memory on whose tiles were whose. I can’t read the emperor. He has been staring at me and nothing else to the point I wonder if he even knows what tiles he needs to complete his melds.

I decide to discard my white tile from the Dragon suit. It’s not a risky move, especially since there are fewer dragon tiles than any other type, so I’ve likely sabotaged someone else’s chances of a meld. I’ve rarely discarded tiles before, especially not the dragon tiles, which I consider a personal keepsake.

“Hu,” the emperor calls as he takes a tile. He flips over his row of tiles as we verify his win and count his points. He wins again. I begin to wonder how I’ll pay the emperor with my life if he wins the full game. If I hand him my head, will he accept it even if he knows I can’t truly die? I wonder how my grandfather felt to have nothing he was willing to give away. I feel the weight of the coins I had earned in my pocket, growing heavier and heavier since my first game of mahjong, not a single coin spent.

“Human greed is vast and endless,” the other dragons and gods had told me, and yet I found nothing to buy nor covet. Like I’d been born hollow, without the magnificence of a dragon nor the desire of a human. In normal births, you inherit an amalgamation of qi from both parents, but the deities had considered my case differently—an imbalance of power, where neither scales nor keratin could coexist, and the deities told me to “let it be” as this is the will of the heavens: the fate of an overconfident grandfather, a dancer who floated on her toes, and a dragon curious but incapable of human love. “It’s like how if you mix too many things, you only end up with a mess,” a young white snake had said. “Those kinds of messes probably don’t belong in the heavens.” But I had never been actively kicked out, only ignored which was fine by me. I preferred to work in silence. Selecting the purest of pearls and grinding them into powder just fine enough for consumption but not degraded into dust required painstaking attention.

My curiosity about what I can offer the emperor overwhelms any desire to win, and I stop actively trying to recognize patterns, instead solely discarding one tile and taking one tile based on the remaining melds I need. I ignore the steals of others’ tiles, focusing only on my row, and as I draw another tile during my turn, I obtain the last match to complete my red dragon pair.

“Hu,” I call.

“Is this where your streak of wins begins?” the emperor asks, a small smile on his face. “I was afraid it wouldn’t happen.”

“It is not always a streak.”

We end up winning the same number of rounds, but the emperor’s total sum of points exceeds mine by three.

I hear murmurs from the crowd, “As expected of the emperor,” and shuffles of hands and coins from those who bet on the winner. I kneel on the ground near the emperor’s feet, close enough that I can see his double-edged sword, and touch my forehead to the ground, hoping my head might suffice as payment.

“Get up. What did you think—that I’d kill you? That’s not very productive.” The emperor pulls me up by my arm. “You can pay me back by joining the palace. I could use a mahjong companion. The harem would treat you well—everyone eats the best meals and spends their time walking around the pavilions.”

“I will join the palace, but not the harem,” I say. “I am not capable of love.”

The emperor chortles. “First I’ve heard that. But very well, you can train as an official’s assistant and continue to play mahjong with me.”

It takes only one month for me to finish my qualifications to become an official, after which the emperor keeps me at his side and waves his hand whenever he wants to play a game of two-person mahjong. I always have the tiles nearby in a wooden box and have learned to build the two walls of tiles in seconds. The emperor watches me work, listening to the taps of the tiles on the table between us, not a single motion wasted. We even play full matches in between breaks for political negotiations with neighboring countries, our moves unfolding in quick succession, one millisecond pauses between the placement of tiles. He claims no one is as challenging and enthralling a partner as me, and moves me into a private palace with a garden and pond of koi. I spend my spare time diligently caring for the koi, but end up feeding them too many pieces of steamed buns and crumbled, overcooked egg yolks, and they end up fat and dead, floating on top of the water. The next day, the dead koi are gone and new koi glide in the pond, small and agile.

It takes only three months for the emperor to ask me to marry him. I can tell his officials are disgruntled, trying to hide distasteful gazes as I pass them to set up a new game. Most of them had their beautiful daughters enter the emperor’s harem, their hopes to join the royal family increasingly futile.

“I will not be able to love you,” I repeat to him. He insists it’s not a problem so long as I am by his side.

“I can be by your side without getting married.”

“The formality of a ceremony is what consecrates the marriage and all it stands for,” he explains.

I continue to refuse even as he grows agitated and forbids servants from sending meals to my palace. But the emperor is unable to forego mahjong and continues to call for my presence. The confusion grows on his face for each game that I appear in the same body, no gaunter than it had been.

“What are you eating? Where have you been getting it from?” he demands.

“Nothing, nowhere,” I answer.

“That’s a lie.”

“I cannot force you to believe me.”

The emperor locks my palace, barring anyone from entering or me from leaving. Only he enters when he seeks me for a game, and I sit at the table waiting for him. I can hear his footsteps growing louder when he approaches the gate entrance, and when the sound is loud enough for me to make out when each of his toes hits the ground, I change into the same white robes embroidered with golden dragons and phoenixes. I comb my hair into a three-ring bun and stab a silver pin through the loops. Despite the lack of food, my palace storage contains enough tea and tea sets which I prepare after boiling a kettle of water. By the time the emperor enters the room, steam rises from the tea kettle and I begin to shuffle the tiles.

“What are you eating? How are you alive?” The emperor always starts our game by asking these questions. His moves have slowed too, as though contemplating the tiles now eats both his mind and stamina. I notice strands of white hair sprouting from his head.

“I cannot die,” I say.

“A heavenly being,” he murmurs in realization. “Will you marry me and take me there? We will be able to play mahjong into eternity.”

“It’s not possible,” I tell him even though it is, just as Father had done so centuries ago, stealing Mother into the clouds. “Humans cannot survive there. They’d soon become husks, their children hollow, crippled seeds from which not even the most fertile of soils can conjure a plant.”

I take the final tile to complete my row. “Hu,” I say, and refill the emperor’s cup of tea.