How do you summarize the forty–year career of a man who’s done everything? Joe R. Lansdale is not merely a writer; he’s one of the most preeminent storytellers of our time. He has written dozens of novels and a hoard of short stories spanning the horror, mystery, and science fiction genres, among many others, for which he’s garnered eight Bram Stoker Awards, the British Fantasy Award, the Edgar Award, and his novelsMucho Mojo(of the Hap Collins and Leonard Pine mystery series) andThe Bottomswere each selected as theNew York TimesNotable Book of the Year. In 2007, he was given the Grand Master Award by the World Horror Convention, and in 2011, he was awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award by the Horror Writers Association. He has also penned scripts for animated film, comic books, and graphic novels forDC Comics,Marvel Comics, andDark Horse Comics. Outside of writing, he established and runs a martial arts studio specializing in Shen Chuan martial arts.

For this issue ofApex Magazine, we are delighted to present to you Joe R. Lansdale’s short story, “Tight Little Stitches in a Dead Man’s Back,” and in the hands of a professional like Mr. Lansdale, you will not be disappointed. Although he is incredibly busy, Mr. Lansdale was kind enough to lend us some of his time for an interview, in which we discussed his lengthy career, killer plants, Batman, and his proclivity for novellas.

About “Tight, Little Stitches in a Dead Man’s Back”

APEX MAGAZINE:Everything about this landscape is unique and fascinating, from the charred ocean floors with the slithering sharks and whales, to the abandoned lighthouse, and the fresh take on botanically zombified corpses. What originally sparked this story for you?

JOE LANSDALE:I always loved all those old science fiction movies where the world changed and was full of mutations the day after the bomb. Not very scientific, but the idea of it, the imagery was very appealing. I also loved the novelThe Day of the Triffids, and of courseNight of the Living Dead, and I wanted to nod to all of that, but approach it from a kind of literary story; a variation on Two People in Connecticut Are Having Trouble With Their Marriage. This is that, but they’re not from Connecticut, and other marriages just think they have problems.

AM:At its core, “Tight Little Stitches in a Dead Man’s Back” is a zombie story, complete with animated corpses and grisly brain–eating. However, although there are shotguns present, not a single weapon is fired in defense against the hoard. What made you decide to focus on the quieter, more desperate angle of two lone individuals trapped and unwilling to fight instead of the gun–slinging that so often dominates zombie stories?

JL:I’ve approached zombie stories all manner of ways. Sometimes traditional, and sometimes not. I generally always have some kind of spin on the things I write, and that’s not by plan or choice. It’s just how I see things. But in this I saw two characters that were defeated by the world and didn’t have the energy to live in it.

AM:Although it only speaks near the end of the story, the tattoo itself is a major player in this tale, serving first and foremost as a substitute for the physical intimacy between the narrator and Mary, and then secondarily as a constant reminder and punishment for the narrator’s guilt over the part he played in the loss of his daughter. This split between intimacy and guilt seems mirrored in the split of his own memories about his daughter, the first of seeing her naked in the bathroom and realizing she’s become a grown woman, and the second, of remembering her riding his back as a six–year–old. Was this parallel something you originally intended to come through in the story, or was it something that the story brought forth on its own during the writing?

JL:The tattoo is all you said it was. It is the obvious symbol for all their woes, concerns, and disappointments, not to mention the main character sees it as a well–deserved punishment, and the wife sees it as part of the punishment he deserves. I found the whole thing unsettling when I was writing it, and thought I was writing a real loser. When I reread it I still felt that way, but, it’s all I had. I started to withdraw it, and then I got this response back that was pretty amazing. The editor liked it, and so did the readers, and in time I grew to love it. It was so dark and I had been in such a dark place writing it I had to have some space before I could appreciate it.

About Writing in General:

AM:I’m going to try to get the fangirling out of the way here, and just say that I remember watching “Perchance to Dream” onBatman: The Animated Serieswhen I was growing up, and it’s still one of my favorite episodes. How did you get involved in writing the several episodes you did for the Batman animated series? Did writing for an animated episode prove more challenging than the writing work you did for comics or graphic novels? Or was it relatively similar?

JL:I loved writing for that series. I was asked by Warner, and I think it was due to my having written a couple of Batman short stories, a novel and a children’s book that dealt with Batman. Also, a friend I knew worked at DC Comics, and I’m sure he put a bug in their ear. They called me one day, asked if I wanted to give it a whirl, and I did. I wrote three for the series, and one for the Batman and Robin series that came later. One forSuperman: The Animated Series. I’ve worked in animation other times as well. I didn’t find it that difficult. I liked it. I like all kinds of writing. Now and again something isn’t quite to someone’s liking, but on the whole, I found it like a cross between film scripts, which I had written and sold, and comics, which I had also written.

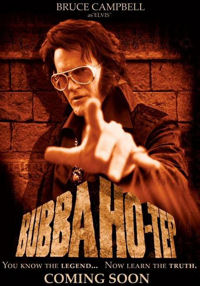

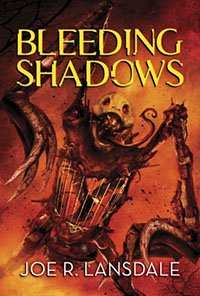

AM:Beyond your many novels and dozens upon dozens of short stories, you’ve also written quite a few novellas, and been nominated for and won Bram Stoker awards for them. (I’m thinking specificallyBubba Ho–tep, On the Far Side of the Cadillac Desert with Dead Folks,among others, and your upcoming collection of shorter fiction,Bleeding Shadows, is said to contain some novellas as well!) There’s something special about works of that length, perhaps because they so perfectly blend the immediacy of a short story with nearly the breathing–room of a novel. Are novellas a form you set out to write deliberately, or did the stories themselves select the form?

JL:The novella is probably my favorite length. That or what used to be called a novelette, a term you don’t see much anymore. But it was usually measured at about 10,000 words. In fact, my first fiction was forMike Shayne Mystery Magazine, and it was given that label. It gives me room to spread and tell a good story without having to write something that would be too long, too much information for a tale that’s better told at novella length. It’s a very natural length for me and I don’t pad anyway, so it’s good when I have a story I can tell and tell to its fullest, but yet, can finish it up with less time invested for a novel. I love reading novellas, and I love writing them.

AM:For the past forty–odd years, you’ve been involved in publishing not only from the writer’s side, but also through editing numerous anthologies. You’ve witnessed much of the ups and downs, from the emergence of splatterpunk in the ’80s to the current trends in zombie and vampire fiction. How do you feel the business of being a writer has changed over the years since you began your career? Do you feel that it’s easier or harder (or the same?) today for an author beginning their career to make a decent living?

JL:The business is always the hardest business in the world anytime you start. For a while, I thought this was the worst time, but actually, a lot of new markets are opening up all the time. The problem is it’s harder to make a real living as a writer, though to tell the truth, a lot of people making a living as a writer didn’t really start until the 1980s. I think we’re having to some extent a self–correction. It was never meant to have this vast readership for all authors, and the money that was there in the eighties, and somewhat in the 90s, just isn’t there anymore, at least not for as many authors as it once was. I think I’ve survived because I always wrote and loved to write a variety of types of fiction, non–fiction, screenplays, short stories, essays, comics, etc. When one thing faltered I had another place to go to, and it was always a place I wanted to go. I also edited anthologies from time to time, and taught at the University here, but believe me, that was more for the joy of it than the money. I’ve always written for me and then hoped someone would love it. Somehow, the money has always shown up and I’m still writing and feel I’m better now than ever. But, I got my foot in the door in the seventies, so maybe it was easier, but I remember people saying, well, it’s too hard now, back in the old days they had all those pulp magazines, and then in the fifties and sixties it was easier because of all those digest magazines and all the book publishers. All true, but it always changes, and there are more markets than people think. What amazes me is how poorly people who claim they want to write often investigate the markets. They have the internet, which actually makes it easier to find markets than in the old days. I wrote for very cheap markets when I started, even some for copies. And that’s another thing, no one wants to start at the bottom anymore. They don’t have the patience to deal with editors, chasing agents, so they just self–publish. I think that’s valid, but it seems to be what so many writers think of as the quickie way out. It’s better to be vetted by the market if that’s possible. You have a book you love, can’t get it published, sure go the self–publish route, but there’s a good chance that will only be marginally better than the “traditional” route. You still have to sell the books. Ebooks, it’s the same. I think they have opened up a whole new world for writers, but they are not a magic answer. Nothing is other than hard work.

AM:You’ve got a wonderful list of writing — I hesitate to call it advice, as advice implies that everyone should follow them (something you yourself would prefer not to imply) — comments on your website. One of the things you mention is that you like to keep a lot of other interests in your life, because if all you had was writing, it would consume you. At least one of those things is Shen Chuan martial arts. How did you become involved in martial arts, and what prompted you to start your own self defense school?

JL:I started studying boxing and wrestling when I was a kid. My father taught me, and that led to me becoming more and more interested. By the time I was thirteen I was beginning to really get serious, and pretty soon I was taking Judo and other martial arts at the Tyler YMCA, and that hooked me. I’ve practiced martial arts and self–defense for nearly fifty years. I love it. And it’s the mindset that’s been important to me. It’s helped me roll with the punches. Also, being a poor kid and a hard worker, and someone who did mostly blue collar jobs until I was 29, I appreciated the chance to make my living a as a writer, and I’ve made the most of it, and martial arts helped me maintain the focus that was necessary.

AM:You’ve said in other interviews that you gravitate so much toward the first–person POV because it reads more like a storyteller’s voice. It’s a first–hand account rather than once or twice removed from the events at hand. You’ve mentioned also that your family always shared stories about the past, such as their experiences during the Great Depression, which served at least in part for the inspiration behindEdge of Dark Water. I’ve been lucky to have a grandfather who is a fabulous storyteller, and I’ll never forget the way he describes the rolling clouds of dust moving toward his farm during the Dust Bowl. Could you tell us a little about how your family’s history of storytelling energized and impacted on your own writing? Do you have a particular favorite story your parents related to you that made a particularly vivid impression on you, more so than others?

JL:Well, a lot of my family’s history, at least pieces of it here and there, as well as tall–tells and stories that are mixtures of truth and myth, have found their way into my fiction in some form or another. My grandmother saw Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. My dad knew Bonnie Parker. He rode the rails. He boxed and wrestled in fairs during the Great Depression. My mother was a talented woman who could create a job out of thin air, something my daughter inherited, so they were my inspirations, and their stories, and the stories of other family members were legion. I stole from them. And yes, I do prefer the first person as a writer and reader. It doesn’t fit all stories, but it’s been the one I’ve written in the most as a novelist.

AM:How has your writing process changed since you first started writing novels? Has it changed? Or is it still relatively the same as it always was?

JL:I used to write from 10:30 until midnight, or two or three pages, whichever came first. I did that and then later I tried a variety of other methods, more hours. I finally settled on three hours in the morning, three to five pages a day, though I didn’t resist writing more pages, or even working at other times of the day if I felt driven. But my plan was three hours a day or three to five pages. Originally I did that five days a week, and then I went to six or seven if I felt the urge. That works for me. I can feel like a hero every day. I revise as I go, and then do a polish when I finish. Sometimes I miss the boat and have to revise more, but that’s the more common process. Of course, sometimes an editor has a suggestion, or a proof reader, but that’s later.

AM:How do you approach editing one of your novels? Is there anything specific you tend to find needs changing on a second run–through, a common challenge? Do you tend to edit a project immediately after finishing it, or do you let it sit for a while? If the latter, do you work on other writing while you let the to–be–edited draft rest?

JL:I edit as I go, and I edit what I call the polish, which is mostly rereading, cutting, revising when necessary. If it takes more than that, I do it. I generally start the polish pretty quick after finishing. I’m less interested in it and do a poorer job if I wait too long. I might be better at catching spelling and typing errors if I wait, but I’m not as good at maintaining the energy. When I do that I tend to polish it well, but I also tend to suck the life out of it. So mostly, I work when a project is still hot. Sometimes I start the final edit the very next day after finishing, but more often than not, I take a day or two off, and in rare cases longer if I have to travel, but I prefer the former.

AM:Another piece of suggested advice you mention on your website is that it is absolutely vital for a writer to read. You compare reading to fuel, and that the more you read, the more fuel you’ve got to write your own fiction. What are you currently reading?

JL:I’m reading a book by an oil field worker. It’s not a literary novel, it’s a memoir, and I’m finding it very interesting. I just finished a while back Susan Hill’s new ghost story book, and I’m starting on John Sayle’s new short story collection. I’ve read a couple of the stories before, elsewhere, but I look forward to it. I love Sayles. Great film maker as well.

AM:You read a lot––somewhere you mentioned nearly three to four books (and/or an equal amount of short fiction) a week––and have also edited numerous anthologies in horror, fantasy, and western genres of fiction. Across all genres, is there any specific thing––be it character, or style, or idea, or etc.––that you especially notice while reading that indicates that a story is going to be special, or at least, special to you?

JL:I set out thinking I’m looking for anything, but style is a lot of it. It doesn’t have to be highly noticeable, just easy to read but with some kind of weight or poetry to it. Raymond Chandler, Ray Bradbury come to mind. I love Hemingway’s style as well, and find it to be a kind of muscular poetry. Fitzgerald is another example. So many. But that’s important. I prefer a story that rolls easy but has some echo beyond the reading. Style and character are probably the most important, but there’s no set rule.

AM:What can we look forward to seeing from you in the coming year?

JL:The Thicketcomes out in September, my new novel fromMulholland, and in November, will be a new short story collection,Bleeding Shadows.

Thank you so much, Mr. Lansdale, for sharing “Tight Little Stitches in a Dead Man’s Back” with us here at Apex, and for sharing your time with us for this interview!