It’s one thing to have the gift of Sight in your dreams, to receive someone else’s answers when you close your eyes. It’s a whole ‘nother thing to understand what those dreams and answers actually mean and how to communicate that to someone who smiles and hopes you’ll say what they want to hear. Cassie was gifted with The Sight as a child, and on that same night she lost the person she cared about most. In her dreams, she sees the destinies and paths of other people, but never her own. Cassie can see just about everything except what she wants for herself. Her inheritance came with a book of maybe instructions, maybe warnings, written by Aunt Dissy and the Dissys who came before. Does Cassie dare read the whole book? Is using the book a contract of sorts that will lock her into a life she didn’t choose for herself? Every day she waits is another night of dreams that leave their marks on her skin.

Heavy with atmosphere and dripping with vividness, “Aunt Dissy’s Policy Dream Book” by Sheree Renée Thomas will take you on a journey into dreams and consciousness, to a place where everything is a symbol that can tell you more. Beyond the gorgeous prose, what I loved most about this story is how Cassie’s house nearly becomes a character unto itself. The home has been in the family for generations, the hall is full of portraits of the women in the family. Nearly all of them are referred to as Dissy, and they visit Cassie in her dreams and teach her how to use The Sight. Living in a home in need of many basic repairs, that theme also infests her dreams. What I wonder is, is Cassie’s gift connected to the house and the Dissy portraits? The plot of the story doesn’t directly deal with those things per se, but I can’t help thinking about if our immediate environment has more effect on our dreams than we think. This is one of those wonderful stories where the plot just scratches the surface of the endless list of variables. I kept returning to this story, rereading large portions of it, seeking out symbols and hints of the grander picture.

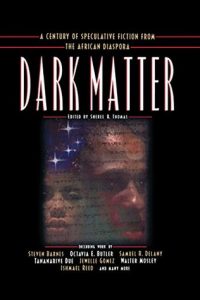

Author Sheree Renée Thomas’s writing career began in Memphis and took her to New York City where she surrounded herself with books and with people who were passionate about books and publishing. Her passion led her to create and edit the Dark Matter anthology, which went on to win the World Fantasy Award in 2001, making her the first black woman to win a World Fantasy Award. Dark Matter’s follow up anthology, Dark Matter: Reading the Bones, garnered another World Fantasy Award in 2005. Her short fiction, poetry, critical reviews, and essays have appeared in Mythic Delirium, Strange Horizons, Memphis Noir, The Ringing Ear, Sycorax’s Daughters, Stories for Chip, Revise the Psalm, Mojo: Conjure Stories, So Long Been Dreaming: Postcolonial Science Fiction & Fantasy, 80! Memories & Reflections of Ursula K. Le Guin, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Rap Pages, and Vibe. Her work has been nominated for the Pushcart award and the Rhysling, and her most recent projects include publishing Sleeping Under the Tree of Life, a collection of poetry and short fiction, and guest editing an issue of Obsidian: Literature and Arts in the African Diaspora.

Sheree was kind enough to chat with me about “Aunt Dissy’s Policy Dream Book,” recurring dreams, her World Fantasy Award-winning anthologies Dark Matter and Dark Matter: Reading the Bones, the joy of getting involved with Obsidian, and more.

APEX MAGAZINE: One of my favorite things about this story is the visuals. When Cassie is dreaming, everything she sees is vivid and saturated with depth and meaning. While you were working on this story, how did you determine how best to verbalize what she was seeing in her dreams? Was it difficult or fairly easy to write the scenes that take place in her dreams?

SHEREE RENÉE THOMAS: With some people and in some traditions, depending on the person or the situation, nearly everything can be “saturated with depth and meaning.” Those who read people and dreams are versed in a whole vocabulary and encyclopedia of signs and symbols. They are trained to pay attention to things that you or I may never notice. Cassie’s dreams weren’t just about perception and symbols, but about hidden emotions, hidden truths. Cassie’s dreams took me to another place—she has the dreams one never wants to have. I’m pleased you enjoyed those images, because they haunted me and kind of freaked me out a bit! And I guess that’s what made writing her story and some of the images so interesting. What I wanted to convey most was the visceral nature of them, and to try to offer readers a glimpse of what it might be like to be haunted by such a burden, such a gift. Cassie is good and weird!

AM: Cassie’s dreams and the Dissys who come to her leave indelible marks on her skin. Scars that are a path to a story of someone else’s dreams. What inspired this story and inspired dreams that leave marks on a person in the physical world?

SRT: Part of the story was born from a question I had about the experience of dreaming. I have had a recurring dream since childhood, and though there have been long stretches and spells when I don’t have it, from time to time it returns. And I haven’t yet sorted out if there is a pattern of when and why. It could just be an old and meaningless neurological loop as some scientists suggest, or it could be a map leading me to a place I have yet to go. We dream and there are so many different theories about the role of dreaming, its true biological and spiritual purpose. So many theories and yet no one truly knows definitively. We wake and sometimes the veil between the imaginary world of our sleep and the reality that greets us, remains with us in ways that quickly fade as the day (or night) goes on. I wondered what it might be like if your dreams—or those of others—took a more lasting toll on us. Once Cassie’s family, the Dissys, came into view, the dreams wrote themselves.

AM: The dream book is a large part of Cassie’s life and of how she makes her living. It is all the knowledge and secrets her ancestors assumed she would need. What is she adding to the book? Who will she pass it on to?

SRT: Cassie will try to avoid the book as long as she can, because it represents a legacy and a responsibility she never asked for. She has no one to pass it on to—or so she thinks—and she questions whether or not what she knows now is even worthy of an entry. Cassie is at the beginning of her journey, and she hasn’t quite stopped thinking about ways to get out of it. What you find is a woman who is trying to deal and still thinks she may be able to negotiate another path. But the Dissys aren’t playing with her!

AM: When she was a little girl and first gained The Sight, she dreamed her room was collapsing around her. Near the end of the story, when she becomes entangled with the man who is haunted by a strange woman in his dreams, the two of them dream together of a house that is falling apart. In their shared dream, they attempt to patch up the house. What is the significance of dreaming that your house is falling apart, and what will fixing it in the dream do for Cassie and this man?

SRT: Now it’s time for a flash of silver, a bit of velvet! Interpreters of dreams and maladies, readers of the bones and divination rarely come to you in a straight path, and when they do, you’d do well to listen carefully. They offer you the in-between path. Some of the signs and symbols are really a game of opposites. A dream that your teeth are falling out could be just as horrific as that sounds or it could mean that you are preparing to experience a rapid period of growth. Like her strange ability, Cassie inherited her mother’s house. Its transformation is perhaps a mirror of her own.

AM: You were the editor for the ground-breaking anthologies Dark Matter and Dark Matter: Reading the Bones, both of which won World Fantasy Awards (in 2001 and 2005 respectively). These anthologies changed African American speculative fiction forever, and readers are grateful. It’s been over fifteen years since Dark Matter was published. Have you seen changes in the world of speculative fiction you’d hoped to see? What has been accomplished and what still needs to be accomplished?

SRT: I never quite know how to answer this question. I started working on Dark Matter in 1998, sold it in 1999, and it was published in 2000. We’re still having the same conversations about the paucity of diversity in the publishing industry that we were having then—except then, people could identify only a handful of black writers actively writing and publishing in the genre. Samuel R. Delany and Nalo Hopkinson spoke about waiting to see that “critical mass” and the inevitable backlash from that.

Good stuff is always being published. We want more “good stuff” and mo’ different good stuff, thank you! Work that reflects other lenses, other values, other world views in addition to the other good stuff that is traditionally published. I couldn’t say if there is a specific number in mind, but there is certainly a lot of encouraging, exciting work being created and shared today in a number of mediums, enough to see the flourishing of multiple communities of speculative writers and artists around the country and around the world. What an amazing, gratifying thing it is to be able to reach for whole volumes of South Asian steampunk, a novel imagining Belgian steampunk, African or Cuban science fiction, or whole volumes of any number of other fascinating bodies of work that might not have been visible two decades ago. If the increasing scholarship and number of Afrofuturism classes are a sign, and the festivals and conferences are a symbol, then new ground is being explored within and beyond the academy and the publishing industry. And that’s progress!

What still needs to be accomplished can be summed up by the lovely album released on my birthday last year by Solange—A Seat at the Table. How much significant, systemic progress and change can be made if you still don’t have a seat at the table? Walter Mosley was organizing around this question in the early 90s via PEN’s Open Book Committee, which I believe he founded, to help bring more people of color into the publishing industry. Why is that vital? Because different people at the table ask different questions, seek different voices, and have a different relationship to all the things we are told are “universal.” Intersectionality matters. Consider what work we wouldn’t get to read if other talented people didn’t get a seat at the table, a chance to guest edit, an opportunity to curate, to be a juror, to host, promote, celebrate, read and review, be reviewed, speak …

AM: Congratulations on 2016’s Sleeping Under the Tree of Life, your recent collection of poetry and short fiction. For readers new to your work, what can you tell us about this collection? How did you decide what pieces belonged in this collection, and which would be better served published solo or alongside other work?

SRT: One of my favorite poets is Lucille Clifton, author of a good number of fine books, including Blessing the Boats, Quilting, and Two-Headed Woman. I may be a two-headed woman, as I write with two hands, stories and poems. I am so fortunate to have editors who appreciate and support multigenre work and multigenre writers. Aqueduct Press, the publisher of my new book and of Shotgun Lullabies, is not only an award-winning feminist speculative fiction publisher but one filled with brave, wonderful genre border-crossers of all sorts. Sleeping Under the Tree of Life is a collection of work that is in conversation with ancient deities and new conjurers, history and mythology, urban and rural, the South and the spaces beyond. I so enjoyed writing the stories and poems included in this special book. The works that were included spoke to the wild rivers, forests, and ruins of my imagination and to my family’s truth. Sleeping Under the Tree of Life is my own strange brew of geography, historiography, and mythology. So happy it’s in the world now!

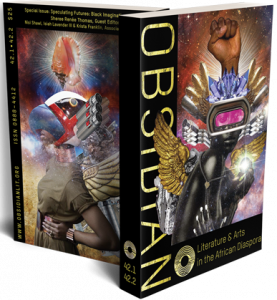

AM: One of your most recent projects includes guest editing an issue of Obsidian: Literature and Arts in the African Diaspora. How did you get involved with Obsidian, and what can you tell us about the experience of guest editing this double volume?

SRT: Thank you for asking. Obsidian and I go way back, but they didn’t know it! I remember discovering copies of the historic literary journal on a shelf at an old library here in Memphis that no longer exists. It was there right alongside Callaloo and I fell in love with both right away. I knew then as a young person who hadn’t even claimed the notion yet, that I wanted to be a writer, and that I wanted to be published in those pages someday. That happened years later, after some personal, generous rejections from the founder, the late Alvin Aubert, a testament that writing and publishing is truly about staying the course, being in the long game as novelists Arthur Flowers and John Oliver Killens teach.

The editor-in-chief Duriel E. Harris, poet and professor at Illinois State University, reached out to me because she had been teaching my work in one of her speculative literature/Afrofuturism classes. I was intrigued by the idea and excited about exploring the Black Imagination and the Arts in a peer-reviewed journal. “Speculating Futures” (vol. 42.1-42.2) is a special full color, double-volume that features original fiction, poetry, drama, scholarship, digital and visual art in Afrofuturism. I was so fortunate to have Nisi Shawl, Isiah Lavender III, and Krista Franklin guest edit with me. After over 40 years of continuous publication, we wanted to re-introduce the journal and celebrate its new home at ISU with something unusual and memorable. With work by writers like Sofia Samatar, Tochi Onyebuchi, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Walidah Imarisha, and other poets, playwrights, filmmakers, visual artists, and scholars, it is a dynamic work. Read it, teach from it, enjoy it, and share it!

AM: What are your favorite themes to create fiction around? Once you come up with an idea, what is your writing process like? How do you go from idea to finished short fiction or poem?

SRT: I like to write about ordinary folks in extraordinary circumstances. Sometimes the folks or the circumstance is rather heartbreaking, like the origin behind my speculative story, “Who Needs the Stars if the Full Moon Loves You?” that was published in January in Revise the Psalm: Writers Celebrate the Work of Gwendolyn Brooks (Curbside Splendor, Chicago). That story came not from a place of inspiration or whimsy, but from a place of pain and fear. We are living in too interesting times, and sometimes that toll impacts you in ways you cannot foresee.

But with most stories I tend to see them first—the characters or their belongings, and then I hear bits and pieces of their dialogue, almost as if I am listening in on a conversation that took place a long time ago—an echo, feedback, coming down the line. I once heard someone describe it as “ear hustling,” and I’ve been laughing about that ever since. I wait to see if more comes, if there is a there there and then I’ll jot down all that I know and all the questions that I have. In the writing and the questioning, the story bits come along and I just gather them together until the narrative begins to unfold and go beyond what I initially imagined. If I had to describe that part of the writing process I might look to the travel notes of the late Geechee Girl, Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor, and call it “vibrational cooking.” The finished work reveals itself after layers and layers of revision and editing, not as spicy but filling! But all of that work is part of what makes writing—and reading—such a magical and rewarding experience. I wouldn’t dream of having it any other way.