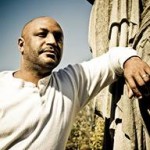

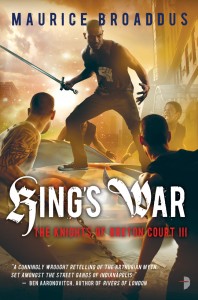

Maurice Broaddus is a successful novelist and prolific short fiction author of science fiction, fantasy, and horror. I would argue that he's one of the more successful African-American male authors writing genre fiction today. Angry Robot Books recently published his Kingmaker Trilogy. His short fiction has appeared in an incredible amount of publications: Cemetery Dance, Lightspeed Magazine, Weird Tales, Apex Magazine, Asimov's, Black Static, and many more.

His short story "Super Duper Fly" (click here to read) in issue 77 marks a triumphant return to our pages for Maurice. The prolific author was gracious enough to grant me a few minutes of his time to interview him about his evocative story.

"Super Duper Fly" is a powerful indictment of America's implicit racism in some of our most popular cultural touchstones. In particular, you place the world's most famous genre author's feet to the fire. Are you surprised that Stephen King doesn't receive more criticism for his casual reliance on racial stereotypes?

Maurice Broaddus: I’m not surprised that he doesn’t receive more criticism for a number of reasons. One, many of us grew up reading Stephen King. We cut our literary teeth on his stories and he was the introduction for many of us to horror. Things I read as a thirteen-year-old boy huddled in my closet reading stuff my mother didn’t want me reading—be it Stephen King or comic books—hold a special place for me. So we are loathe to be too hard on our heroes. Plus, in trying to give our heroes the benefit of the doubt, the trope probably arose from a good place (or benign negligence if I’m giving less benefit). He was aware that his cast was largely monochromatic and wanted to diversify it and figured giving a prominent role in the hero’s journey to a minority was a way to diversify with a significant role.

But good place or not, it is not above criticism. Another one of my heroes, Spike Lee, back in 2001 during a lecture discussing the power of images and how they can hurt started referring to what he called the “super duper magical Negro.” Chesya Burke broke down the idea of the “Super Duper Sexual Spiritual Black Woman”. And Nnedi Okorafor, in particular, wrestled with “Stephen King's Super-Duper Magical Negroes”. So you can see where my story got its name (besides me being a fan of Missy Elliott).

Your story opened my eyes to how many black racial stereotypes exists in American culture, including, but not limited to: The Mammy, The Buck, The Tom, The Mulatto, The Coon, and The Magical Negro (the primary focus in "Super Duper Fly"). With so many popular films and books in our stream of consciousness using these stereotypes, do you feel that our society will ever reach a point of shedding racist depictions for entertainment?

If you truly want to have your eyes open, you should read Donald Bogle’s seminal work, Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies and Bucks: An Interpretative History of Blacks in Films. It’s a devastating history/indictment of how black people have been portrayed in cinema. Believing that society will eventually shed its racist depictions of people requires a greater faith in humanity than I have. However, things will get better. The reason we have continual images/depictions of us as mammies, toms, bucks, tragic mulattoes, coons, and magical negroes is because other people have been telling our stories. That’s what it boils down to: if you’re not telling your story, other people will. If you just glance at my list of people who were criticizing, you see artists/storytellers who are the rising tide of us telling and defining our own stories.

In your introduction that accompanies "Super Duper Fly", you end with a comment that comes across as both comic and tragic:

"Sometimes I’m grateful just to see a reflection of me included in the story. Other times I don’t think that my story is being respected and I get all stabby."

I know this is an issue beyond the purview of an individual author, but something that needs to be addressed by the whole of society. Still, can you suggest a starting point on how we can address this Titanic-sized cultural issue?

I can’t speak for society or for black people or for other creatives. And, in some ways, I’m not taking that on as an individual artist.

As a black artist, in particular, I am extremely conscious of several things. That I am still one of a relatively few number of speculative fiction writers of color. That image is important, that we have too few depictions of our stories so that each one carries with it greater weight than it should. There is also the unspoken, yet very present, social responsibility to the community in terms of the stories we tell and the characters we craft. So while I am conscious of these things, when I sit down to write, I push that aside because thinking about my social responsibilities while writing is crippling. My job is to 1) please/entertain myself with whatever story I am telling; 2) tell the best story I can. My job is to be true to myself as an artist. My job is to keep telling my stories, fight for those stories to be seen, and nurture up and coming storytellers as best as I can. If I can crack the door of opportunity open just a little bit more for the next person to get through, I’ve done my job. So I guess my starting point within my reach is me. And the cultural starting point is with each artist. Art is how ideas, how new ways of looking at things, are spread throughout society.

There is a dichotomy at work in "Super Duper Fly" that I feel works on a sub-conscious level: the problems of the Caucasian characters are mundane and dull while the issues facing your black characters involve fantasy tropes and actual agenda. Do you feel like black people and culture are too often equated with otherworldly and fictional fantasy elements such as elves, dwarfs, and magic?

Do you mean why are black people so often put in this mystical role (especially to help white protagonists)? I suspect the reason lies in what defines a magical Negro (Native American, Asian, etc). In part, it is their mysterious nature. By that I mean, their stories aren’t explained. They enter the story from some mysterious place, have no particular background, and disappear back to wherever it was they came from. In other words, they aren’t known and are thus “othered”. As The Other, they are deprived of story and are simply a story element. It’s easy to tokenize or fetishize people and cultures we don’t know. Which goes back to your question about where do we start. Telling, listening, and sharing in one another’s stories is difficult work, but when people are known, it is hard to make them The Other. If we’ve done our jobs as writers (and people), there are no The Other. There are characters we’re trying to get to know.

While I recognize that you're riffing on overused black stereotypesin "Super Duper Fly", it seems to me you could write a series of shorts to subvert each of the racial tropes you mention in the story. Is this something you would consider doing?

I think subconsciously I may be doing that. My first novella published was this story called "Devil’s Marionette." Some people have described it as my angriest work. I was wrestling with the idea/image of The Coon. (Ironically, Spike Lee was wrestling with the same territory as his movie Bamboozled came out at about the same time.) A few years ago, I wrote a story called "The Cracker Trap", where I was wrestling with the idea of “the black guy who dies first” (We need a better name for that trope. The Sacrifice seems a little too on point). In fact, "Super Duper Fly" is that character’s “evolution” and make no mistake, one of my goals as a writer is to subvert this "Pantheon of Black Stereotypes"™. But rather than spend time deconstructing the past of how we’ve been depicted, I’d rather create whole new stories.