The Whole Foods where Justin works is a block from the beach, close enough to smell it. Apart from the rusting cars in the parking lot and the blood-spattered branches on the Eucalypts, the store looks much the same as it always did. Justin can do his job as he always had, mostly, except for the barbed manacle around his ankle. This extends from a hole in the floor near the 100% Organic Zone to the loading bay out the back, then past the Allegro Handcrafted Coffee Station—out the front entrance and left to a whisky bar next door called Moustache.

Moustache is owned by the same corporation that owns Whole Foods. It is where Justin is allowed to go on Tuesday and Friday nights, as a reward for his excellent performance. He is the only customer at the bar now, which gets lonely, but on the upside, their playlist is pretty good. Plus, he has his pick of any single malt from over four hundred. He’s had plenty of time, since the beginning of the end of the world, to count them. So far, since the end of the end, a little over six months ago when the last three customers in the store were vaporized into a cloud of gore, he has sampled fifty different whiskies from all over the planet. He’d have to say his favorite so far was a close shave between an eighteen-year-old Yamasaki and a forty-eight-year-old Brora. Justin once tried to go past the whisky bar to the barbershop next door (also owned by the same conglomerate), but the suckers on the inside of the manacle sunk their teeth into his ankle just at the threshold, so he didn’t try that again.

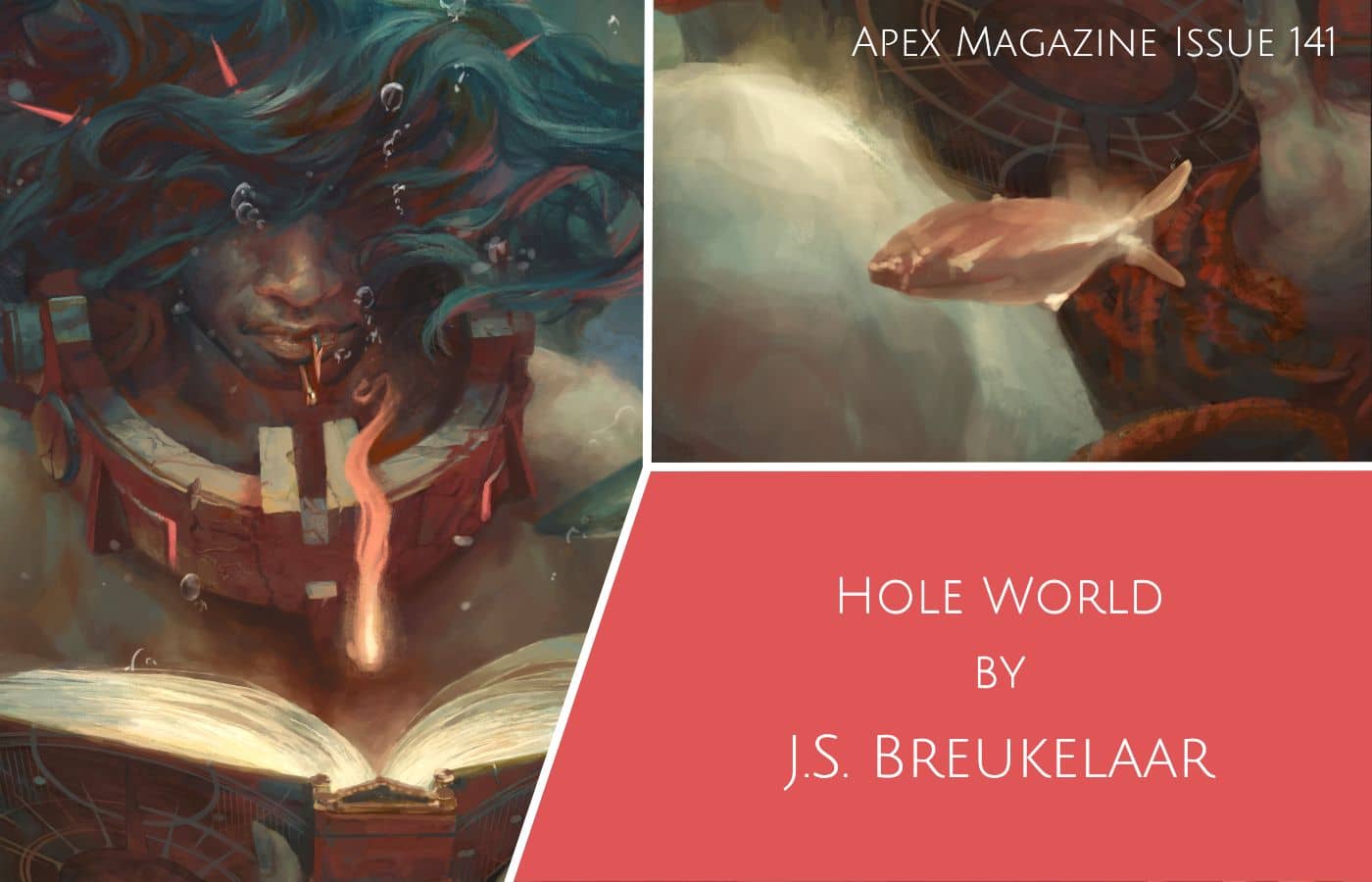

The W has fallen off the sign across the front of the store, so now it says “hole Foods” with the signature apple leaf (or peach) fluttering from the o. They could even be angel wings, Justin supposes. Not that he believes in angels anymore.

The corporate playlist, Upbeat Alternatives, pipes 24/7 throughout the store when the grid’s up. Justin has his choice of organic pumpkin chips and his favorite brand of blue corn salsa. But his appetite isn’t what it was, despite the fact that his chores take more effort because of having to drag the shackle around, wrapped python-like at his ankle. He doesn’t like to think of the hole in the ground where it comes from. At night he falls asleep with the noise-cancelling headphones on that had been a gift from his sister Tania. He sleeps on a cot in the storeroom, which had doubled as an office once. At 9 pm, the door to the storeroom locks from the outside, the tentacle fitting snugly into the six-inch hole cut from the corner of the bottom rail, where rats or termites might once have gnawed if they knew how to draw a perfect circle.

Justin still wears his black uniform apron with his name tag. He carefully washes the blood off it after inventory, which is what the managers called it on the list of regulations they left for him six months ago, along with the thing around his ankle. He sits hunched in his underwear while his uniform goes around in the drier like a lunatic ghost. Sometimes he just hangs it on a nail and it’s always dry by morning. It is hot when it doesn’t rain, and it is always a dry heat.

He remembers the scattered appearance of all those refrigerated containers at the edge of woods and neighborhoods around the world. Communications were still operating then. Broadcast news stations, social media, bloggers, and podcasters all had different explanations. They were all wrong.

Electricity is sporadic but mostly still runs in the fridges and freezers because that is where the meat is kept. He tries not to think about which crimson cube is Tania.

The delivery comes in every Monday in a refrigerated truck driven by a faceless employee, someone probably kept on, like Justin, because they were good at their job. Or maybe just because they were at the right place at the right time. Justin’s sister always said that being at the right place at the right time is an art in itself. But Justin isn’t so sure. He wasn’t the real meat guy. On the day the world ended, Justin, who worked in Home Shop mainly, was scheduled for a performance review that would possibly lead to a small promotion. But the meat guy went home with Covid, so Justin got called over to fill in. That’s where he was when the holes opened up where no holes had been before, wearing the meat guy’s apron and pushing a steel dolly stacked with animal-welfare-certified organic beef. No art in that. Just pure dumb luck.

Where were you, Tania? Picking up lattes for the production team? Recording a demo for some new band? Where were you when I saw, too late, your five missed calls?

Justin does not look at the truck driver. There is an amateur wobble to the way they reverse the truck. And they always brake as far from the bay as possible, as if afraid of reversing into it. This means that Justin has to stretch awkwardly into the open steel doors, which is hard on his back.

He wonders how many of them are left. And if any escaped.

On this Monday, Justin knows right away that it’s a different driver. Steadying himself against the dolly, he watches the expert three-point turn, the tentacle dancing out of the way. The reversing signal all but occluding a punk metal mix thudding from the speakers. The last driver did not have a playlist, and Justin wonders if this is a reward for acing a Performance Review. Slitting his eyes into the ashy light, he can just make out the neat opening cut into the lower edge of the driver door panel, the tentacle emerging from it and snaking off into the distance. But how Justin knows it’s a different driver is the way they handle the rig. Smooth as silk, like his sister handled her Miata. The tentacle lashing the air, they back it in right to the edge of the bay, so that Justin does not have to lean in or drag his own shackle further than necessary.

Justin’s hair is beginning to thin, despite the organic argan oil that he rubs into it once a week. He wonders about toxins in the air released with all the exploding body parts. Maybe he’s breathing in too much iron. Or bacteria from stomach and bowels left to rot in the dry heat or run in the torrential rains. He recalls the open and unfixed eyes of the last eviscerated customer. Thinking about it makes him lick his cracked lips, opening up a blister just to taste the blood on his tongue.

“One day,” Justin imagines telling his rescuers, “these things came out of holes in the earth and started killing people. It was mass panic. The faces were a blur. The air misted with a fine red spray. People took refuge here, in my store.” He calls it his store, because even back then, it was all he had.

“But they killed them all in the end,” his rescuer would say. “Why not you?” Justin imagines him as a cute medic, or reporter maybe. With Japanese tortoiseshell glasses and an expensive haircut.

Justin doesn’t know why he’s been kept on. Why he isn’t already dead meat.

He’d read Nineteen-Eighty-Four a long time ago, in high school. He’d hated how the proles came to truly love Big Brother. In their hearts. He’d been bullied at school, and at that time, he couldn’t understand ever learning to love your tormentors. Now it is his greatest fear. He wakes up sometimes so hungry for love he thinks he’d eat anything.

Is that why they keep him on?

Rescuer: “What if you’d refused to do your job? Went on strike?”

He has thought about this too, stopping work and just dangling his legs over the side of the loading bay until the associated Performance Review that would see him chopped into bite-sized cubes for inventory. He has wondered if there is a replacement for him somewhere, one of a herd of humans kept in some barn underground to replenish the supply of slaves and food (same thing). Maybe Tania is there, he wonders, and maybe there is still time. But just as he is about to ask, the truck rumbles to life and his imagined rescuer recedes into a swirling fog of lost hope.

So Justin unloads the last of the delivery, shuts the big steel doors, bangs twice with the flat of his hand, and steps away. The big white truck eases out smooth and silent as a whale.

The next Monday morning, the new driver backs the rig right up to the bay like in the previous week. Justin loads the last box of meat onto the stack beside the one remaining dolly. There had been a second one that got a flat tire after Justin began working for the new management, and he hid it in the back of the storeroom so as not to have it come up in a Performance Review. It is a big delivery and Justin is wearing his back support belt. He is concentrating on bracing around a heavy Styrofoam box, so it is a long minute or two before he registers that the driver has wound down the window and has actually said something to him.

“Lovely day for it.”

Justin dumbly watches the reflection of a woman’s face materialize in the side mirror. It has been more than six months since he’s heard a human voice, apart from the vocals on the Upbeat Alternatives playlist, and Justin isn’t even sure these are actually human voices. His sister had been in the recording industry and once told him that half the songs they produced for jingles and corporate playlists were AI produced—human voices being way to pitchy, she said. Cheaper to fake it than to pay for real talent.

Justin at first thinks that the four words are just part of the song on the playlist, but he knows them all, and “Lovely day for it” isn’t in any of them. Plus the driver’s voice sounds distinctly human, no offence, and way too pitchy.

She says it again.

Justin doesn’t sleep well because of his nightmares, and he registers a slippage between the movement of her mouth and the words reaching his ears like a dialogue track unsynchronized from a film. At the shock of her voice he lets the Styrofoam box slip from his hands. It lands awkwardly at the top of the stack but with the lid still in his gloved grasp, exposing the glistening blocks of red meat. Each measuring four inches a side. Bite-sized, he assumes, depending on the mouth. He quickly presses the lid back in place, nervously eyeing the security camera pointed across the loading bay.

Justin can vaguely remember a time of mystery shoppers, spies who worked for HR, and how any lapse in customer service would inevitably be reported and lead to a performance review. A colleague in meats had scored badly with a mystery shopper by failing to assure them that the crunchy breading on the vegan Turk’y cutlets was both non-GMO and gluten free. Justin wonders how many of those fake shoppers are now bite-sized cubes of meat packed into Styrofoam crates at the end of the world.

“I’m Kelly.” The driver raises her voice over the clash of playlists. A tremor of misgiving travels up Justin’s spine. Surely that’s against regulations—only essential communications between store staff and drivers are allowed. Her arm rests along the window, a square hand with a wedding and engagement ring, hint of a tattoo under the rolled-up sleeve, and a loose yellow braid under the corporate cap.

Blood from the hunks of maybe mystery-shopper meat has smeared on Justin’s shirt and he suffers a bad moment thinking about some of it leaking into his mouth.

“Careful,” the driver says into the side mirror, movement behind her dark shades clearly following Justin’s gaze at the juicy cubes. “Once you’ve tasted chocolate, it’s hard to go back to vanilla.”

Justin can only croak in reply because he hasn’t used his voice since singing along to Upbeat Alternatives started to make him feel like he was losing his mind. Only the lower half of the driver’s face is visible. A strong jawline, seamed flesh.

“Have you seen my sister?” Justin asks. “Her name is …”

But the words flutter and fall into the space between the boxes of cubed human flesh and the waiting truck. The driver brings her arm back inside the cab and rolls up the window. Hits the ignition. Justin just stares at the flapping steel doors and forgets what he’s meant to do. The truck growls and then he quickly pulls the latch across, hits it twice, and watches it sail away.

He gets the meat into the store, unloads, and comes back for the rest. His chest is tight. He wonders why there was a new driver and why she decided to talk to him. The words toll in his head like a bell. Lovely. Day. For. It. He packs most of the delivery onto steel shelves in the big freezers. He wheezes along to the playlist, trying to find his voice.

He arranges the rest of the cubes in the 5 Step Animal Welfare refrigerated display, as instructed. This is where most of the so-called inventory takes place, which is what the new managers called it on the instructions they left for him. Justin doesn’t want to think about another word for whatever leaves the whole area so tacky and slippery with blood that he must scrub it with a steel brush and hot soapy water. The blocks of meat each weigh just under a pound and a half—635 grams to be exact. It is minced or shredded or in strips, depending, he imagines, on the cut. The color varies from vibrant crimson to pale pink to a brick red. Each cube is shrink-wrapped in a transparent membrane, which is probably edible like the paper on some candies, because he never sees any sign of it after inventory. The membrane is stamped with different ideograms which might be the equivalent of “leg” or “shoulder” or “liver” or “heart” or maybe none of those. He tries not to look too closely at the words. Or the meat. It has long since stopped making him nauseous, and that’s what he worries about now even more than a Performance Review.

The anxiety wears him thin, not to mention the long days and unspeakable nights locked in his room. So that he sometimes considers giving in to the yearning, submitting to the unmistakable intentions of the tentacle, erotically nuzzling his ankle, its silver scales swollen with promise.

But then he sees Tania in the crowds around the street courts. Rising to her feet at his winning three-pointer, skinny arms raised high above her head, eyes closed and her nostrils quivering. Smelling the sea.

Smelling escape.

Justin runs through the checklist of his chores, but his thoughts swim away like a shoal of startled fish. A whisky would level him out. But the regulations were very clear on his nights off: Tuesday and Friday. He recalls with a twist of despair the sounds of their slaughter, a legion of moans carried in on the wind. The blurred faces, here and not here. He washes and dries his filthy apron and T-shirt and then he lies on his cot and thinks about the driver and the rings on her fingers, sparkling in the sunlight of another lovely day.

A week later she is back, an hour behind schedule. “Supply chain issues,” she barks out the open window. Justin has been waiting for the truck since before dawn, his eyes puffy from weeping. The tentacle is restive behind him, waiting too. The new managers had removed all the knives, axes, saws. Oh, but he’d tried to hurt it, all the same. Battered it with a garbage can, dropped a display shelf on it, poured bleach, acid, and gasoline (even though they’d taken all the matches too). It just sat there, implacable as a ship’s rope. Does it hear? Does it see? In some dreams, it’s connected to a vast stomach at the core of the Earth. In others, it’s one of the legs of a giant metallic spider or spiders like the Sentinels in The Matrix. In still others, whatever he’s attached to is the weapon of something much worse.

The driver rests her hand on the edge of the window. Her tentacle extends out the gap in the lower corner of the door, its serrated scales gently palpating.

Does it breathe?

“Highway between Ranch Road and Windyside is flooded. Had to take the coast road.”

Justin has not heard those names or any mention of the world beyond Hole Foods for half a year.

“Forecast’s for more of the same,” Justin manages, sounding like a grotesque imitation of his own dad.

“Practiced on our sins,” the driver says.

Justin just grunts and gets to work.

The next week she is late. Justin has slid onto the floor beside the dolly, his head on his knees. He watches her back the truck in, straight as an arrow, but it is inches from the loading bay when he finally manages to unfold his complaining limbs into a standing position. The same playlist as before, some song that’s an AI’s idea of a punk metal concoction, frothy as one of the cakes in Sweet Spot, and he asks her what it’s called.

“Lemme see.” She turns to some screen on the dashboard. “Well, I do believe this number is ‘Kiss My Axe.’”

The creases at the edge of her eyes deepen, and her lips curl up in a smile as unpracticed as his. For a while they both just grimace at each other like that, smiling with all of their teeth.

Over the next couple of weeks she comes back, later each time, and she rolls down the window and talks to him over the music. Words began to come back to him. Words beyond the vocabulary on the Upbeat Alternative soundtrack. Words like road and rain and drive and fear and Kelly and Justin.

“Are there others?” he asks once.

“I don’t see anyone except the warehouse guy,” Kelly answers. “I sleep in the truck, shower and shit and eat at the depot. Warehouse guy brings the meat out. I load it. That’s it.”

Justin wonders, with a pang of jealousy, if she talks to the warehouse guy, too.

The fourth week is hot again, but the driver doesn’t turn up. He waits until dusk, feeling pieces of himself falling away, like a headland collapsed into the sea. Then he shambles to the freezers to pull out the required inventory to stack in the 5 Step Animal Welfare display window. What if they notice the empty freezer shelves? He’s supposed to keep them full. That’s his job. What if he gets called into a Performance Review?

His uniform shirt is soaked in a sour-smelling perspiration. How can he explain that the inventory issue is not his fault without blaming her? He looks down at the cube of red minced meat in his gloved hands. His teeth start to chatter. The shackle tightens around his ankle.

Justin shaves before his shower, careful not to look at his eyes in the mirror, not wanting to see the hunger there. The day you stop wanting to see your own reflection, his old man had said once, it’s probably already too late.

Justin had begun a diary soon after the new management had taken over. There were plenty of recycled paper notebooks in the Home Shop section, and it seemed like a good opportunity to make sense of what was happening to the world. It wasn’t. Nineteen Eighty-Four began with Winston deciding to keep a diary, which was the beginning of the end. Justin knew that the end had already begun, just like Winston did, so what was the point?

The point was protest. The point was Winston’s refusal to let the Party turn him into one of them. It was heroic, but wrong. They got him in the end by using the very humanity that he tried to weaponize against him. Justin looks down at the living shackle around his ankle. The sickeningly toothy tickle. It’s an extension of him now, like a limb or tail. This is who he is becoming. And there is no way to break free.

Except meat. He’d die for just one bite.

He makes himself a meal of spelt pocket with white bean hummus and cashew cheese. Then he vomits it all up in the toilet and has a scalding shower to wash away the shame and grief.

After his shower Justin writes the word “HOPE” over the reflection of his eyes in the steamed-up mirror. By the time he dries off, it is gone.

The next day is Tuesday. The managers had come as scheduled, emptied the display cases. There is no way of knowing if they noticed the meat missing from the freezer. After mopping up the blood and scrubbing steep moraines of slop from the floor, he begins on the shelves of sauces and condiments, which are near enough to the refrigerated display to be spattered after inventory. It is early afternoon when he finishes. He tries to think of other chores he can do to buttress the crumbling wall of sanity around him. The ambient cajole of the soundtrack seems to be coming from the tentacle itself, drawing him closer to the fridges, closer to the meat.

Then, he hears the truck.

Justin forgets to breathe. He hobbles out, the tentacle sullenly swooshing behind him.

“Don’t ask,” she says, rolling down the window.

So he doesn’t. He unlatches the steel doors and begins to heave the boxes of meat onto the dolly with gloved hands he can barely feel. His tall, once athletic body has wasted away to skin and bone, his joints swollen and his balance unreliable. Sticking to a regular workout routine was easy at first, but soon it went the way of writing in his diary and singing along to Upbeat Alternatives. The truck driver averts her gaze so he won’t feel self-conscious about his stooped frame and faltering hands.

“Lovely day for it,” Justin says when the meat is all out of the truck.

She dips her chin in reply. Brings her arm in and goes for the window button.

“Wait.” He waves his hands in the air like a drowning man. “Can I get you a drink? A glass of water or a soda or something?”

Surely offering a thirsty driver a drinkis an essential communication, although he might already be skating on thin ice with the inventory breach last week. She reaches over and brings out a thermos in reply, jiggles it out the window.

“I’m good,” she says over the engine, and steers the rig out into the falling light.

That night, Justin sits alone at Moustache drinking a Japanese single malt called Rei straight from the bottle. The silence inside him rising to a shriek that mutes the Rock the Nineties soundtrack. Is the blue Earth now red from space? Are there Hole Foods in China, in Macedonia, in Australia? How many other workers like him and the driver are connected via some twitchy tentacle to a giant mouth deep beneath the Earth?

If that’s what it is.

He’d spoken to Tania at her office on the morning of the day the world ended. “I can smell the ocean,” he’d said.

“Good luck at your performance review,” she’d said. “Maybe they’ll make you a manager already.”

Now all you can smell is meat. Not even the single-origin coffee he grinds fresh every day, the aroma of single malt, the musk of his wet dreams—nothing—drowns out the smell of blood.

He’s combed the store for poisons, pills, guns, knives, belts, ropes—the tentacle won’t quite reach to the rafters for him to throw himself off. He can feel an evil triumph emanating from it, an unflinching intelligence that he can, in his darkest hours, taste on the back of this throat, bittersweet and fiery, like an overripe fruit brought back from a secret and forbidden place.

The next Tuesday, the driver is back in the late afternoon. She rolls down the window, and there are blotches on her freckled face, a trickle of sweat at her temple. It is so hot that a scarlet leakage has begun to trickle down the side of some of the Styrofoam boxes. He feels her eye on his manacle. He grunts as he moves, like an old man.

When he finishes, he latches the truck doors and weakly slaps them twice. But she doesn’t start the engine right away. He peers at the reflection of her dark glasses and he wonders if she wears them all the time, the better not to see the hunger in herself.

“How about that drink?” she says.

Justin pivots so quickly that his groin pops and the suction cups at his ankle sizzle. He goes to the beer fridge, ignoring the drag of the manacle, and grabs a sixpack of Hopping Turtle Ales and a packet of Xtra Dark pretzels. By the time he gets back outside, she has moved the truck so that it’s parked sideways along the bay.

“So you can you reach,” she explains, already perched on the hood.

He glimpses a rosy anklet of scar tissue peeking out from the hem of her jeans, the tentacle suspended from her manacle above the asphalt and unreeling into some distant hellish hole. He shudders, even as he takes a dark comfort in them both being part of the same giant mechanism.

“You don’t have to get the truck back?” he asks.

She extends a hand and he takes it to scramble awkwardly beside her, feeling the heat of the truck through his uniform. He passes her the beer, puts the pretzels between them. High up here, it is easy to imagine the ocean again, even if he can’t smell it. Justin strains his ears to hear.

“Depot’s not far away. It’ll be back before dark.”

They softly clink bottles.

“Well,” she says. “This is my first beer since …”

But the words eat themselves. There is no language yet to describe the world.

“I blacked out, or they knocked me out,” he says. “I came to with this around my ankle, and a typed list of instructions. Holes carved into all the doors I was allowed through.”

She looks to be about forty, ten-odd years older than him, a brassy blond with freckles and a broad back. She is not the rescuer he’d imagined, but angels never are.

“I woke up in the truck,” she says. “Same thing around my ankle. Hole in the door—different set of instructions stuck to the windshield. There was a teddy bear on the hood and a human eye lying on the passenger side. Assumed it was my predecessor’s.”

“He must have failed his Performance Review,” Justin says with a half-drunk giggle.

She looks at him curiously, but before he can explain, she points to the manacle and shakes her head. She has a long horizontal scar across her neck, and she notices him staring. Lifts up her finger, with the diamond ring, and makes a slitting motion at her throat. “Didn’t work,” she says in a low voice. “Just made a terrible mess.” She finishes her beer and climbs off the hood and he does too, his knees screaming as he lands.

“Steady,” she says, and gets in behind the wheel, slamming the door as the tentacle snuggles into its circular groove.

He watches the truck disappear in a red smear of light.

After he gets out of the shower, the word has materialized again on the mirror. That night at Moustache, he drinks to hope.

She is back next week, but on the Monday this time, with no explanation. He is waiting with beers. He feels both daring and terrified, knowing he’ll have to be quick packing the meat away before inventory. They sit on the hood, and she tells him she’d been married to a man in the military called Leonard. Long haul trucking helped with the loneliness during his deployments.

“No kids,” she says. “Praise be.”

The beer tastes a little off, and Justin’s throat wants to close up at every sip. Maybe he is allergic to it after all this time. “Do you like whisky?”

“Take it or leave it.”

“Tuesday is my night off,” he says. “There’s this whisky bar next door.”

“Depends on the roster.” She flips a braid over her shoulder and lowers herself back into the truck.

By the time Justin gets inside, it is after eight and he will have to hurry to get the meat away in time for inventory. The beer has made him sluggish, his gut churning from the impact of all those carbs and sugars. The warm glow of having another human to talk to is quickly leavened by the fear of being locked outside his room after hours. As nine o’clock looms, the sweat is cold on his back and he can smell his body odor beneath the congealed blood. Only in his wildest nightmares can Justin picture the orgy of bloody appetence, and he knows that witnessing it for real will be the end of him, either way.

What would he do to save himself?

What wouldn’t he do?

The freezer stock thankfully replenished, he flings the cubes of meat into the 5 Step Animal Welfare display case in disgust. For what species of mouth are these bite-sized, he wonders, and which cube is Leonard?

Justin finally gets to his room, no time for a hot shower tonight, the taste of pennies in his mouth. He is halfway through cleaning the blood off his skin with tea-tree wipes when he remembers that he’s forgotten to put away the dolly.

A cold wave of horror convulses across his chest. This is the first time he’s made such a mistake, and it is a clear violation of the rules. But even as he considers racing out (hobbled as he is) to put it away, the outer lock snicks shut. The tentacle spins a little in its hole, as if trying to get comfortable. Inventory begins before he can even get his headphones on. He hears the sucking sounds as the managers emerge and start to rhythmically crunch and slurp. The feeding is accompanied by that humming ululation at some frequency barely detectable but felt, like a catchy trill, in his bones and in his crumbling soul.

He shoves the headphones on. Why didn’t the managers take them along with everything else? Maybe they don’t know what they are. How they’re the only thing between him and the siren sounds of the inventory. He thinks about Winston and the rats. He thinks about eating Kelly.

Finally he takes his ten mil of valerian as per guidelines, and curls on his bed facing the wall. He dreams about his sister, a fringed dress she loved when she was ten, five years younger than Justin but so much older. Maybe that’s the reason she reaches for Justin’s hand when they get to the mouth of the alleyway behind the projects that lead to the streetball courts. She swings something on the end of a ribbon or string—he can’t make out what it is. She keeps his winnings safe in a pencil case, hidden from the old man, because it is their running-away fund.

He wakes to the ever-present wheedle of Upbeat Alternatives. His eyes are puffy and he licks salt off his lips. It is almost dawn. He pulls on his uniform and lumbers to work. The dolly is still there, covered with gore.

He drags it to the loading bay, carefully cleans it, making sure to wear gloves and a mask. He gives the whole inventory area an extra good wash, disinfects the fridges and floor. He mends his apron. All that week he makes sure that inventory is as smooth as possible and that the cubes of meat are stacked extra straight for the managers’ convenience. Instead of wearing his noise-cancelling headphones right away, he makes himself listen to them eat. Trying to build up resistance, train himself like a commando. But the sonic slurry wins every time. In the end he must jam on the headphones before he tears a strip from his own flesh.

On Friday evening he sits alone at Moustache and nurses a peaty dram from Tasmania called 606 and has an early night.

Kelly doesn’t turn up the next week, and even if it’s not related to the dolly incident, he takes that as both punishment and warning.

The following Tuesday at sunset the truck rolls in. Justin loads the meat, handling the boxes carefully.

“Nice night for it,” Kelly says, fixing him with a raised eyebrow above her shades so he can get her meaning.

She slowly pulls the truck out and inches it around the block to the front of the store, where the tentacle around her ankle can reach into Moustache. That gives him enough time to get most of the meat squared away. He joins her inside, breathless and sweaty. They must leave the door ajar due to there being only one hole in it for Justin’s tentacle, and the dark and silent night rushes in.

She pulls up a stool but keeps her cap on and gestures he does the same.

“They got a special sense for heads,” she says with her lips brushing against his cheek.

So Justin puts on one of the Moustache caps from the merchandise locker and pours them both a twenty-four-year-old Isle of Arran single malt, the yellow pale as her hair.

They kiss glasses.

She looks around the walls glimmering with bottles of varying sizes, the whisky pale-wheat to spun gold to lava red. The playlist is on high volume. He can sense her shackled foot tapping on the rung of the stool.

He points to a dusty bottle, the whisky a primordial amber. “That one there is a collector’s item. God knows what it’s doing here of all places. It’s forty years old, single malt, from an obscure still in Scotland that mostly does blends.” Is every block of meat one person, like a single malt, or are some blends, like cheap whisky? “Only a couple hundred bottles made.”

“You take all your dates here?” she says.

“The last one I did.”

“Who was he?”

Their heads were very close together. Justin wonders about the truck parked outside the store and her tentacle curling around the edge of the door, but by now he is beginning to understand that sight isn’t the managers’ strongest sense, not seeing in the way he understands it.

“My sister introduced us,” Justin says. “He worked at the same studio as she did. He sang backup and jingles but was trying to make his own record. Tania said he had perfect pitch.”

“Which is?”

“Being able to recreate any musical note perfectly without having to hear it.”

“Like sing it?”

He nods. “Or name it. You have, kind of like a tuning fork in your head. It’s pretty rare. Like one in ten thousand. Mariah Carey, Michael Jackson …” But saying the names aloud, that’s too much. He feels a welling sob. Wishes he could take the precious words back, swallow them whole.

“Dead meat,” she says with a stagey shrug. Her performative indifference is as unconvincing as his.

He can smell diesel in her hair and her clothes, Altoids on her breath.

“Will we be prisoners forever?” he asks.

“Only way to not be a prisoner is to become a warden,” she says. “No good choices.”

“I call them managers.”

“Whatever,” she says.

“Because if we … eat …” he begins.

“Then, we’re like them.” She lifts her shoulders and lets them drop in defeat. “Seems like.”

“Or?

“Or might be another way …”

“Kiss my axe?” he says so softly that he can’t be sure she hears him.

“Just below the knee,” she says. “It won’t notice right away, and by the time it does, you’re gone, is the idea.”

The suckers on Justin’s manacle chafe, and he closes his eyes in surrender to the tender heat. Just breathe.

When he opens his eyes, she is pouring another shot. He mutters, half to himself, “You’d bleed out, surely.”

“So? At least that’d make us worthless to them. We wouldn’t end up sliced and diced.” She cocks her head, listening. “Hell, I did once love this song.”

“Care to dance?” he asks.

He takes her in his arms, and she clasps her strong hands around his neck. They sway together, gently so as not to wake up their shackles, to a slow sad song about coming clean.

“I feel so hungry,” he whispers into her hair.

“Me too,” she says.

“Were they us once?”

“Maybe. Listen.” Her living heart pounds against his. “And no matter what I say, keep dancing. I talk to people. On the road, making deliveries.”

Again, he feels that dark twist of jealousy.

“There are rumors about some who got free. Didn’t bleed out or die from the amputation or get caught trying to escape. You understand?” Justin’s arms tingle with goose bumps. “The word is that they travel by night, timing it for the feeding frenzy. Going off-road; apparently, the holes appear only on dry land, not in water—which makes sense. Rivers are good, lakes are better, ocean is best. Some colony off the coast of Oregon, Tillamook way. There’s a small island, half submerged now, survivors on crutches and canes. But alive.”

He might faint. Like hearing Santa Claus is real. On crutches and a cane but alive. Stinking of infection, mutilated, but alive.

And free.

His knees seize up before the song ends, and she releases him. Pours them both another shot.

“But the managers took all the …” He makes a cutting motion. “Anything that can be used …” He wiggles his foot, and the manacle tightens.

“Rainbows and unicorns,” she says. “So forget it.”

But he can’t. He feels something coming to life deep inside him. A remembering. Of a different kind of greed, a different kind of hunger. He remembers the silk of a hot city night as he cut through it to get to the rim, to dangle weightlessly in a moment of victory and defiance pure as the rarest whisky. Purer. All of the guys on the team were straight. All except one.

“Maybe though,” he swallows, “the managers are not as smart as they think. As they were when they were us.”

“Too much meat,” she says with a yellow-toothed scowl, “rots the brain, Leonard always said.”

Justin’s heart is like a deceased bud, its petals gone leathery from grief and greed. But watered into life now, by whisky and words. Maybe. “What if the ones that surface to feed are just doing their job. Same as we were once. Just dumb proles …”

“Proles?”

“Grunts,” he says, “part of a much larger thing. Like a corporation, or nation, or army. But you know, underground and with tentacles.”

Kelly nods slowly. “The grunts come in and out of holes to harvest the food, then set up an infrastructure—that’s us—to supply rations at various depots interconnected by a network of tunnels. Makes sense.”

“What does it want?” Justin asks. “The thing that runs it all?”

A ripple of helpless terror passes across her face, draws the color from it. “Want is everything,” she whispers, “because it makes everything else nothing. But Leonard had this book, The Art of War. He’d read from it to put me to sleep.” She stops, takes a swallow of whisky. “One thing I remember. Don’t send reinforcements everywhere, or everywhere you’ll be weak.”

The managers missed the dolly when he left it out. Dripping with carnage, like everything else, maybe they couldn’t see it.

“If you’re only thinking about what you want,” Justin says, thinking about his old man, “maybe you’re missing something.”

After their father found the pencil case, there was hell to pay. So Justin played better and harder, and Tania found a new hiding place. She never gave up on him, so he never gave up on himself.

“Nothing can see everything.” Kelly chews her chapped lips, stops before she can draw blood. “Not even God.”

The next day, nursing a terrible hangover, Justin finds the broken dolly at the back of the loading bay. He rubs it down with blood-smeared rags and carries it to his room. Even though they’d taken all the knives, anything blade-like at all, they’d left tools for Justin to make repairs when needed. He finds a hammer and a wrench and some pliers. That night, instead of taking his valerian right away, he puts on his headphones and begins to take apart the dolly.

He can only work while they feed, and even then, he worries that they’ll hear the squeal of the wrench, or once, the clang of the broken wheel when he drops it onto the cement. He lays out towels and his quilt on the floor after that and works on those. Finally manages to get the nose plate free. It’s the size of sheet of paper, same size as the instructions they left for him. Their ravening awakens the ache inside him, and he welcomes it like a two-timing lover. Come on, he says, make me hungry. See if you can get me to lick your slops, my tongue in your secret places, see if you can make me one of you.

The manacle grows slack and trusting, complacent in its waiting game.

The next week, Kelly comes on a Monday and doesn’t make eye contact. He knows it is to avoid suspicion after Moustache, which has to have been against regulations.

The week after that, she comes on a Tuesday.

“Night off?”

It almost kills him to loudly he doesn’t feel well. Her eyes, glassy-blue and bloodshot over the top of the shades, ask a question.

“You ever read Nineteen Eighty-Four?” he answers her unspoken question with another, thoughts of Winston and Julia in his head.

Kelly brings a plastic water bottle to her lips, wipes her chin with a fine, freckled hand.

“It’s about a totalitarian regime called Oceania. The hero is Winston. And he meets Julia, also a hero. He learns to trust her. And,” Justin doesn’t know how to finish, “that goes badly.”

“She betrays him?”

“They betray each other,” Justin says. “Oceania wins.”

“It always does,” she says pointedly. “Except when it doesn’t.”

He slams the steel doors closed. The back of his eyes prickle with tears.

The last time, she comes earlier, too early for beer, but he’s standing on the bay with a sixpack just the same. After he’s unloaded the meat, they get up on the hood. It’s a rare day, sunny but not too hot, the smell of rain in the air.

“I’m drinking beer,” she says, “but I’m thinking of whisky.”

“Would you? Do it?” he whispers, close enough to rub shoulders.

She looks down at the hood, pretends to buff something off its surface with the cuff of her shirt. “Just below the knee. Crutches at the ready. Then then move like the wind.”

After they finish the beer, she brusquely pulls the rig out in a sob of gears. Whatever day she comes next week, if she comes, he will not be there to meet her. Rainbows and unicorns, maybe. But she was real and made him real again to himself, and he owes her for that. Making something real means that you never want to eat it.

He feels the need to write, if only to keep track of his thoughts. He scribbles in the steam on the bathroom mirror in a kind of made-up shorthand, leaving out conjunctions, punctuation, any word that doesn’t come easily. If it doesn’t come, it doesn’t matter. He writes about his progress. Ten push-ups. Then twenty. Then fifty. Pull-ups wearing a backpack filled with cans. How he’s made an oblong patch of cement in the bathroom by crowbarring up some tiles. How he’s begun to sharpen the steel plate by dragging one edge, and then the other, against the cement, under cover of inventory. Some memory of his father’s talk of homemade shivs in prison. How the blade is sharp enough now to slice through a pumpkin. Soon he’ll try one of the hardcover cookbooks in Home Shop. He’s fashioned crutches from some scraps of a bloodstained pallet from the dumpster where he tosses broken Styrofoam meat boxes. He’s glued a couple of grips onto two corners of the blade to better make it work like a chef’s guillotine. He’ll try a block of wood next week. In the steam, he scribbles his own inventory list: oxy he’s raided from purses and backpacks left in the store, half a bottle of antibiotics he was lucky to find behind the counter at Moustache, ibuprofen for the road, garlic pills for infection and vampires, tourniquet, bandages, rags to stuff in his mouth to muffle the screams, disinfectant. Plus plenty of whisky.

“For courage,” he writes.

He thinks about the nights trapped in his room before Kelly came along. The time he wasted. Not wanting to forego his visits to Moustache in case it arouses suspicion, he goes as usual every Tuesday and Friday, but only has one drink, and he leaves early. He finds a basketball in the staff lockers and dribbles up and down the aisles, dragging the tentacle behind him like a sullen pet, a sulky child.

Locked in his room, he tries the sharpened cleaver on a leg of venison from the Wildfoods Section, rock hard and encrusted with ice. He sits down and positions the leg close to where his own leg would be. He brings the cleaver down as hard as he can. It hits bone with a jarring thud. The second time, the blade that little bit sharper, his muscles just that little bit stronger, it cuts straight through. That night he checks his backpack, takes a double dose of valerian, and he sleeps like the dead. In his dreams, he sees Tania running ahead of him in the alleyway, the fringes on her dress fluttering, and he can finally make out what’s swinging on that ribbon in her hand.

It is a seashell. On his last night at Moustache, he waits for the song to come on that he and Kelly danced to, the one about having someone to breathe with. Before he leaves the bar, he takes the unopened forty-year-old single malt down from the shelf. He dusts it off and brings it to his room, dragging the tentacle behind him. He has covered the bathroom mirror with his notes, careful not to write over the first and last word, HOPE. On the bedside table, next to his supplies, the cyclopic eye of the whisky keeps fiery watch. He begins to drink, thinking of where in Moustache he will hide the blade, once he’s finished with it, for Kelly to find.