“I’ve decided.” Atha spoke over a cup of pungent wildflower tea, freshly brewed for the occasion, flavored with honey. “Bury me in this tree.”

It wasn’t a surprise, so I simply nodded. My cup was empty. Moderns don’t need food, after all. Atha had brought me a cup anyway, a courtesy I wasn’t sure I believed in.

“Any other requests?” I lifted the empty cup and placed it against my lips, mimicking his actions. Wildflower tea was probably similar to Earl Grey, I decided, and called for the taste of sun-ripened citrus and gently warmed tea leaves bursting across my tongue. Delicious, every time. “Any bequeathments? Next of kin I should inform? Estates to be managed?”

Atha peered into his cup. The sparse hair combed neatly over his nearly translucent scalp would have been striking on any Modern, but Atha was an Oldie, natural and organic. His sickly appearance wasn’t choice, but necessity.

“What’s your name?”

“Ryegrass.”

“Wonderful. What a wonderful name.” Atha nodded slowly, pleased with himself. “The last Promisor styled themself Ambition.”

The conversation lulled. Atha continued to stare at me. His eyes were curiously watery, and I wondered if the moisture was uncomfortable. Outside his little hut, the wind whistled across the grass. I tuned the frequencies out. The sounds were distracting.

“Why Ryegrass?”

“It smells nice after being cut.”

“You only think it smells nice.”

I didn’t say anything. Oldies were like that sometimes. Lived and downloaded experiences were identical. Science proved it, every Modern knew it, but some Oldies still believed certain special intangibles couldn’t be understood through collective memory. I supposed Atha was one of them.

“Anything else, Atha?”

“Yes.” His smile spread wide across paper-thin skin, wrinkles folding in on themselves as his face filled with joy. “I have a bequest. The garden is yours, Ryegrass.”

“For how long?” Annoying old man. He knew I wouldn’t refuse. Moderns lived long enough that taking care of his garden for a few dozen years wasn’t a big ask, and I’d chosen to be his last Promise. “Ten years? Twenty?”

“For as long as you want it.”

“I don’t want it.”

“Then it won’t be yours very long.” Atha rose slowly. “Which is fine, because it’s all yours. Nobody else’s though, just yours.”

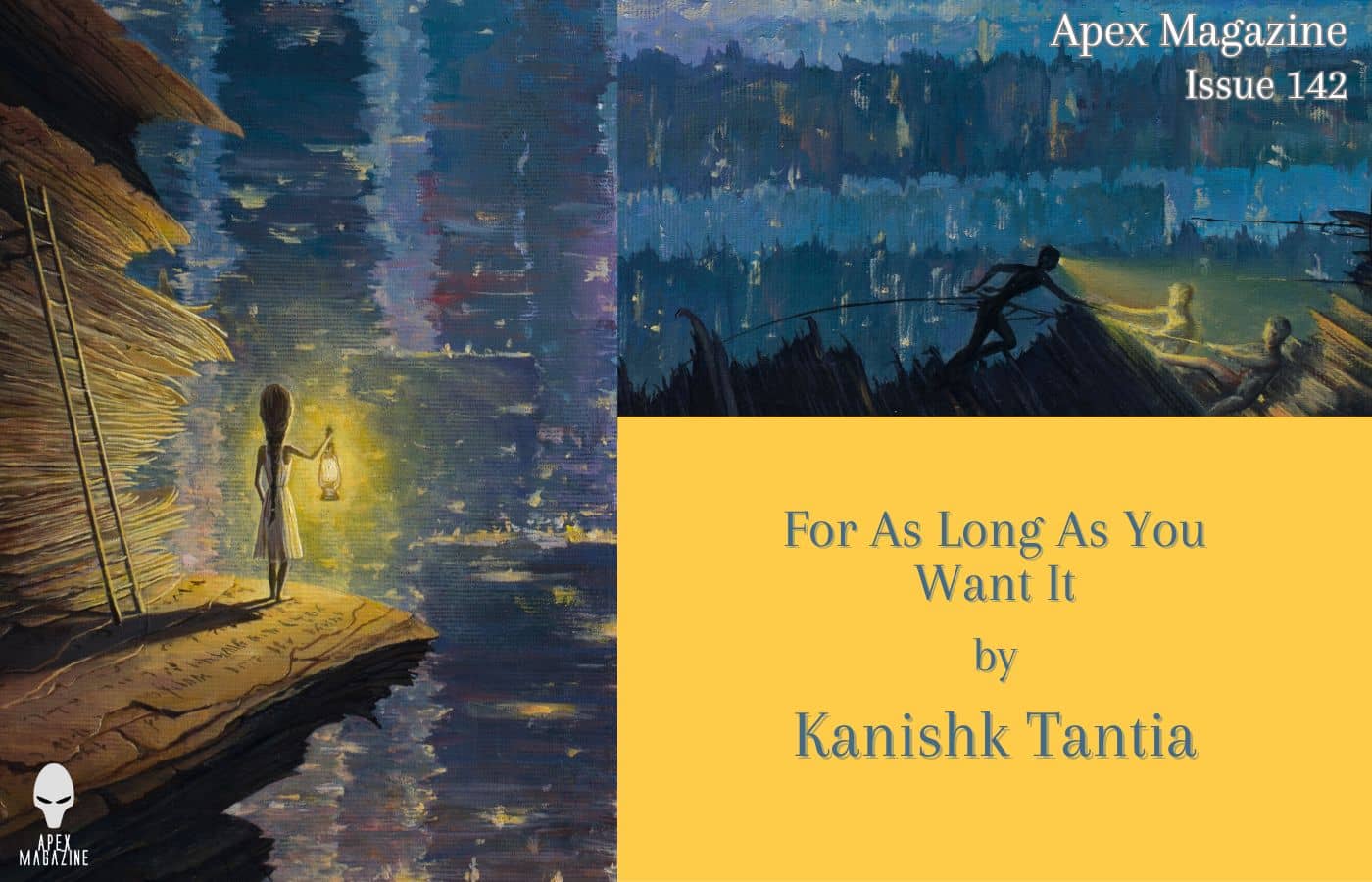

Atha shut himself inside his hut, leaving me outside under the spreading banyan tree. Stars speckled the inky blanket of night. As golden dawn burst through the sky, I decided to ask Atha to donate the garden to a museum, to people who wanted to preserve such things. I had only volunteered to fulfill a Promise for an Oldie dying alone, not to care.

But when I knocked on his door, only the echoing of plastic on wood greeted me. Atha had the last word, after all.

True to the Promise, I buried him within the tree, settling on a gnarled, weather-beaten limb overlooking his hut. Atha’s frail body would fit inside any branch, but I spent a long time ensuring my choice was perfect. I don’t know why. I didn’t need to.

Once the bark cocooned him, I closed the wound, sealing it with sap. Millions of botanists and arborists lived within my mind, guiding me. These were trivial endeavors.

But this was only the beginning of the Promise. The rest was harder.

At first, I intended to let the garden die. I sat under the banyan tree and watched plants wilt and grass brown until weeds choked the flowers and crumpled petals floated to the ground. Gardeners and botanists and preservationists in my memory twitched uncomfortably but were easy to ignore. This wasn’t food or medicine. It wasn’t important. It was a garden; pretty, but useless. And I already knew what every plant tasted like, what they smelled like, what they felt like. The memories lived in my head.

When the earth browned and cracked, when the grass dried and scattered into the winds, when the weeds ran rampant, I thought my work was done. Promise fulfilled. Only the banyan tree remained, but even a Modern can’t wait for a tree to die. And cutting the tree down felt wrong, useless though it was. Atha still lay within the branches. His corpse was probably a desiccated husk, leathery skin clinging to his bones as the substance of Atha ran through the banyan tree he’d cared for his whole life.

I didn’t understand why Atha chose to die. Who dies anymore? I would have converted him if he asked, brought him into the collective.

I only saw the sapling as I prepared to leave forever. Maybe if I hadn’t, I would be in the city now. But I saw it, a little green shoot surrounded by dry ground, growing in the shadow of Atha’s branch, sucking water from a marginally damper patch of ground, alive only through luck.

I would wait, I decided. Unlike the banyan tree, the sapling wouldn’t last long.

Maybe the sapling knew. Maybe it grew entirely out of spite. Either way, it survived, and eventually, the botanists pleading within my collective memory won. After months of watching the little shoot struggle, I broke.

We have memories of watering plants, but actually showering a plant in water and watching dust drenched leaves turn green is different. Memories are perfect, the glossy, distilled experience of thousands of lifetimes. But reality has the benefits of imperfection.

The soft moisture of freshly cut ryegrass underfoot. The damp, earthy smell of it. The rough texture of an ancient banyan tree, watching, laughing as the wind whistles through its leaves. The sharp, bitter taste of wildflower tea, which is nothing at all like Earl Grey. The collective doesn’t need such imperfections, but we should still remember they exist.

The collective smooths every experience into a gentle, easy hum, except for the one it erases entirely. But plants should grow, and thrive, and pass on. Journeys should end. Atha needed an ending, and I think I will, too.

You won’t believe me. And that’s okay. But, when it’s time, bury me in the banyan tree. Find a branch that’s sturdy and firm. You’ll know how. We all do.

And of course: The garden is yours, for as long as you want it.