Dream-weaver, pain-cleaver

We’re on a brown raffia mata in my room. The sound and rhythm from Mama’s throat beg me to return to myself, to not let the pain lure me away. With dancing fingers, she braids air over my face into magic lilac sparks. I smell flowers. The pain that hangs on my spine and around my hips cleaves in half. The world begins to dim away, reality turning into dream. I stand in the middle of a field of halimores, an ocean of orange, fiery petals rustling in the breeze. Mama remembers how much I loved this plant as a child, the sap within it. I walk toward one, I run, movements my muscles are starting to forget in the waking world. Nectar. Sugar blooms on the back of my mouth. For a while, I forget my pain and its shadow song over me.

Home

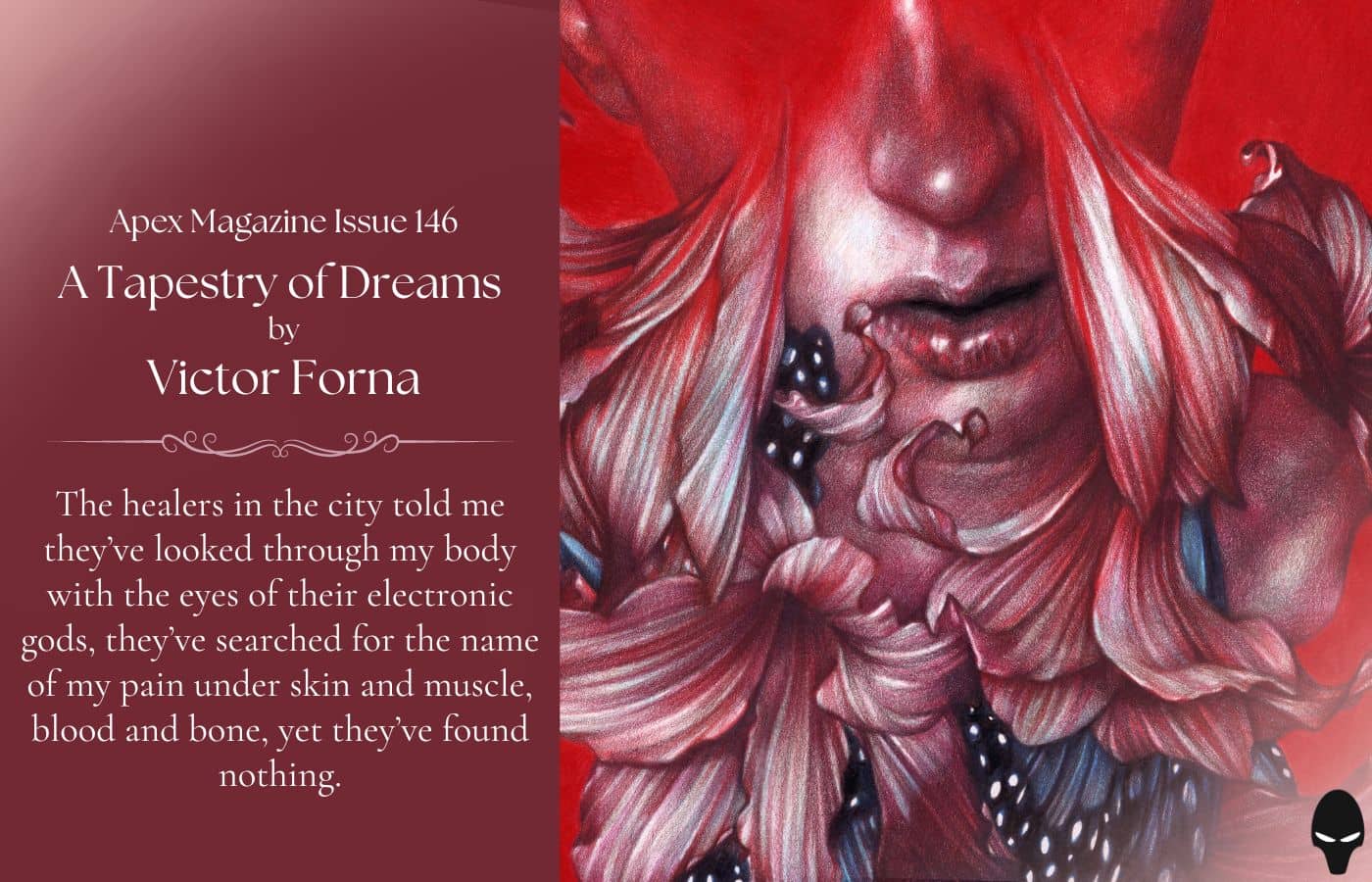

The healers in the city told me they’ve looked through my body with the eyes of their electronic gods, they’ve searched for the name of my pain under skin and muscle, blood and bone, yet they’ve found nothing. No story whispers inside of me why I hurt so much, saws gnawing my spine. I think of my body as a tree, with branches, and the saws, giant and afloat, cutting in. How will the doctors heal a thing they cannot name? Broken, confused, I call Mama. Hearing my cries, my sobs, her first-born child, she begs I return to the village, she begs I return home to her. We are here for you, she whispers, makes music, there’s no shame in coming back to us.

Dream-breaker, root-seeker

When Papa enters my room, he shatters the dream Mama’s hands are weaving for me, shrapnel of images darting away.

“No luck,” he says to Mama, tired, lost, hurting man.

Mama returns to her weaving, silence and sadness weighs her lips. My heart cracks with hers. Will I die? Everyday Papa comes empty-handed, the fear rushes through me.

“Have you eaten, hm?”

“Not now,” Mama answers.

“Come eat with me.”

“Don’t you have a family to go to,” she says, tone like a sting. “Your new wife and son? I will eat at my own time. Leave us.”

Papa doesn’t leave.

He calls Mama’s name that way only he knows, that never fails to make her smile.

In the half-light of the room, Mama doesn’t smile. She begins to chant her magic again, voice shrill. She stops. “You said you’d bring this medicine. It’s been how many days? First it was pain, now sleep. You know what’s after.”

“I know, I know. And I will get the tida. Something keeps hindering me in Nomse … you know those forests ... I will go again tomorrow.” He sighs. “She will come back from this. She is strong. All you do will not be in vain. And I promise—”

“No. No more promises from you.” Her words, though scolding, are also filled with unnamed ache.

Papa hesitates.

He walks over to us, and kneels at Mama’s side. He kneads her shoulders. “Relax. Calm down. I’m sorry for all I have put you through. You deserve better.”

He’s right.

Mama deserves someone better than him—I feel a pang of pain at the thought that creeps in next: she deserves someone better than me. I’m a burden to her. I’ve taken so much from Mama over the years … and now …

Papa hugs her.

He’s a man hard to hate.

“Relax. Calm down.” Mama laughs dryly, pushing him away. She shakes her head. “I can’t deal with you right now. I can’t deal with anything else. Please, leave. I need to concentrate.”

She weaves my dreams on. I’m watching from the vantage of a setting sun. Two silhouettes; Mama meets Papa for the first time on a village road. I sense the leap in her heart, the love, the rage, the longing. She tries and fails to change the scene.

Expectations

“I don’t want to die,” I tell Mama on my first night back in the village. I sit at her feet, in the open yard, beneath the stars. “I feel like I won’t survive ...”

She’s undoing my city hair. She prepares to braid it in ancestral patterns, circles, spirals, and sanctify me. “You’ll not die,” she says, curtly.

“I am just afraid. I know there’s power in the tongue.”

“We know the old ways here. You don’t need to do anything.”

“I will not die.”

“Good … I will keep you safe.”

“Papa hasn’t been able to look at me since my return. I can’t tell if it’s my sickness he can’t face, or if it’s because of what he did to us.”

“It has to be the latter. You know how he’s always been afraid of you. He’s ashamed. Stupid man. You’re the jewel of his eyes, the child he brags about.”

I laugh against cramps. “Who leaves their wife of more than twenty years? Their six children. He surprised me.”

“He says this woman is the love of his life. He dared to tell me that. As though I should understand. What was I, all these years, then? What does she have that I don’t? He still brings goods for me, but, that aside, he has abandoned us. If not for my business or the allowance you send …” Whispering magic into the parts she makes, Mama begins to braid my hair. She says after a while, “Sometimes, I think I still love the fool. And I hope this hasn’t turned you off marriage.”

“You know relationships are not for me. We’ve spoken about this …”

“I dream of grandchildren. And before you say I have other kids. I dream of your children.”

“We shall see, Mama, we shall see,” I reply, sleepy, drowsy, even my skin hurts. Mama always finds a way to land here.

“It doesn’t matter, anyway.” She rubs madoni in my strands, lemon-scented nostalgia, taking me back to childhood. “I’m so very proud of all you’ve accomplished. School. Work. The way you’ve held yourself. I’m proud of you. Never forget that. I hope your sisters will follow you. Have you spoken to them since your return?”

“I think they all went out when they heard I was coming?”

“What happened to you guys? You used to be so close.”

“I wish I knew … it’s my fault … I’m the eldest. Sometimes it feels like they hate me for how I was always sickly growing up? I took so much of the love that should’ve been theirs. I don’t know. I’m so tired, Mama. I’ll make peace with them before leaving for the city.” There’s much still expected of me, I understand, but, tonight, I just want to get out of the pain.

Truth-sayer, food-bringer

In the dream, Mama’s dream for me, I’m strong, my bones haven’t betrayed me. No pain. No painsong tries to lure me away. No endless sleeping. I’m married. I have kids, all girls. I own an office in one of the skyscrapers in Rokoli City. Money poured in me, time, love, haven’t gone in vain. The sun burns bright in the sky, warm against my face—the dream begins to let me go: pain returns, like a thorned kiss, like a hateful embrace, humming through the dreamscape, and into my spine.

“You need to eat and rest. How much weight have you lost these months? I brought food,” our granny says from the door, in her yellow frock, pale-blue night at her back. Even after all of Mama’s warning, she still speaks as if I can’t hear her. Everybody does, and they all ask for the world to go on … that Mama goes on … and I want her to, but I also don’t want to die.

I don’t know what to feel.

Mama loses focus. “If I stop the dreams, she dies. You know that. I don’t have time to stop. To eat. Not until we find the tida. Not until we can wake her up.”

“It’s rice and okra.”

“Why does everyone want me to eat? You expect me to eat and sleep and talk and breathe?”

“We need you here.”

“She needs me …”

“Oh, my daughter.”

“My husband will find the root. I will eat and rest then. I will hoe my lands. I will live when my daughter isn’t dying.”

“That useless husband.” Our granny walks toward us. “Look at your eyes, they are fading. I will feed you. You will weave dreams with your hands and eat from mine. I know in giving dreams, your body takes and owns some of her pain. I watched this magic drain my mother. I wish it skipped you as it skipped me. We all love the child, but it is better sometimes to let nature take its course. Eat, my daughter. Stop. Just a little while,” our granny says … Granny who loves me so much. She used to take me to school, we’d walk for miles and miles, laughing. She used to carry and dance with me.

“I’d take all her pain if I could.”

Petrichor fills my nostrils.

“Eat. What if you die, my daughter? What about the other children? How do you think they feel about all this?”

Tears on the edges of my eyes.

“Mama, stop,” Mama says. “Children who wouldn’t even come visit their sick sister. Why do they hate her so much? What did she ever do to them? They know how much she does for this family, they know. She has always given to us, when was the last time any of us gave to her?”

I begin to sink into another dream, leaving the wars of relationships above: a brown-tinted dream where my pain has no voice.

Mama chants and groans.

Stop. Eat. Rest. I can’t say these words to her. I want to. Breathe, Mama. Go to my sibling, sit with them, hold them—maybe that’s why they hate me so much. Exist for someone other than me. Exist for yourself. I give you permission to let me die.

I’m skipping in the rain, a child again, playing with long forgotten friends.

When I jump, I fly.

Painsong

By the time Papa returns with the tida from Nomse Forest, I’m already dead.

Dead, but not yet gone to Roratha the Spirit World.

So I hear him, like I heard Mama and my siblings, cousins, hear him crumble and wail at the herald of my passing.

“Our child is gone.” Mama dashes into the hands of this man who’s hurt her deeper than anyone else, because he’s still the only peace she knows. She clings onto him. He begins to tremble. “It was my fault. I slept. I told her she wasn’t going to die. I told her I will keep her safe. But I slept. My best friend. My daughter. She followed the songs of her pains.” I thought my death would free Mama, but look at how she shatters in the hands of the world. I want to hold her, tell her I’m sorry, tell her everything will be fine.

Papa’s voice breaks. “If only I’d brought the medicine earlier.”

The whole village by the river’s edge mourns me in the nascent light of dawn. I hear them all, as I walk closer to the wooden gates of Roratha the Spirit World.

Because grief trumps logic, Papa frees himself from his family—a family that only comes together when sorrow wrings around their necks.

He brings out his dagger.

Men in our village never show their vulnerability to the world, but Papa lets his bloom like a flower. Crying, he scrapes the wizened and soil-covered skin of the tida. It’s strange to see him so broken, so weightless … hurting man.

He prepares the mystical tuber against advice that it only works on the half-dead, that he’s wasting the magic on me. With a pestle, he pounds the root in a mortar, calling the name of an ancestor at each hit, begging them to not let me through the final gates. He squeezes blue liquid from the pulp into a small calabash.

He enters the room where my dead body lies. Hoping, shaking, he pours the bitter liquid into my breathless mouth.

He sits beside me, head in his hands, and weeps. “My one in the hundred,” he says like prayer, as Mama joins his side … together again in the ache of my death as they’d been in the joy of my birth.

And they lament, parents and siblings, and the rest of my family, about everything they regret. Why do we fight each other? Why go years without us talking? Why break the promises we make to each other? What are these battles of life when death looms over us all?

The dead only walk forward—toward those wooden gates of Roratha the Spirit World, but I realise, a sudden instinct, that I can walk backward—toward life again.

Step-taker, choice-maker

In the case wherein I step forward, the direction of death, because the dead must stay dead, I’ll be welcomed into the Spirit World by my ancestors. They will don colourful gowns when they greet me. They will have golden bangles on their wrists that clash as they dance for me. They will be proud. They will sing my story, sing my life. My song will be short but beautiful. They will say I was the hope of a people. They will say I made it against all odds. They will say I was my mother’s child. They will say I was the jewel of my father’s eye. They will tell me the name of my pain, my painsong, at which I’ll laugh and laugh and laugh, for answers and names have no meaning to the dead. I’ll find peace among the spirits, free of all once expected of me.

None of this is certain.

In the same case wherein I step forward, the direction of death, because the dead must stay dead, I’ll be dragged through the Spirit World by gods who are angry with me. They will bind me in chains. They will beat me with wires of fire. They will ask me why I chose the city over them—why didn’t I make use of the magic they gave my blood? I’ll scream for all of time, blood beading the sides of my mouth.

This, too, is merely one possibility, nothing solid. If I step forward, maybe I’ll wish to have stepped backward. Maybe not.

In the case wherein I step backward, the direction of life, because my heart hums for the living, I’ll be welcomed back by the sight of my parents entwined. They will call for relatives. They will call for neighbours. I’ll be filled with pain. My bones will be bent. My face will be twisted. Every move I make will be a sacrifice to an ache I still cannot name. I’ll never go back to the city. I’ll never realise my dreams or my parents’ dreams for me. The heartbreak for my suffering will push Mama and Papa further from each other. I’ll be shunned. I’ll be pointed at, whispered about for returning from the dead. I’ll never accept that my pain is not punishment for mine or someone else’s sin. I’ll die on a dusty roadside, again, alone and forlorn.

None of this is certain.

In the same case wherein I step backward, the direction of life, because my heart hums for the living, I’ll be welcomed by the sight of my parents entwined. They will leap in joy. Their embrace will be warm and tight, sweet on my skin. They will call for relatives. They will call for neighbours. They will thank the ancestral spirits for returning me to them. I’ll be filled with joy. My pain will be gone, my painsong silent. I’ll move my limbs again. In the happiness for my resurrection, my parents will love once more. I’ll return to the city. I’ll own an office in a skyscraper. I’ll relearn the old magic in my veins. My story will bring others closer to their spirits. My siblings will turn out okay, the spaces between us will be filled. We’ll find peace. I’ll give romance a chance, I’ll call that girl.

This, too, is merely one possibility in an array of futures like halimore petals. If I step backward, maybe I’ll wish to have stepped forward. Maybe not.

What’s an end, if not a choice?