When I was a teenager living in Munich, Germany, I would spend long hours browsing at a secondhand bookstore named Anglia English Bookshop. (For the curious, this was located on Schellingstraße 3, near the University, and has since been replaced by The Lost Weekend Coffee Shop and Bookstore). One fine afternoon I hit on a compact but bountiful trove, two trade paperbacks whose slender size belied the infinite riches within: The Complete Book of Science Fiction and Fantasy Lists (1983) by Maxim Jakubowski and Malcolm Edwards and The Illustrated Book of Science Fiction Lists (1982) by Mike Ashley. Opening them up at various random pages (“The 6 Shortest SF Writing Careers,” “7 SF Writers Who Have Appeared in Films,” “Twelve SF Stories of New Ice Ages,” “Twenty-two Double-Headed Pseudonyms,” “The Cosmic Season List,” and so on) I was immediately entranced and could barely tear my eyes away from the contents long enough to pay for them and study them more assiduously on the train ride back home.

Over the next few years I would come to realize that science fiction and fantasy were uniquely festooned with such checklists, tabulations, indexes, enumerations, catalogs, and bibliographies. The two books I’ve mentioned offered views into genre history and attitudes, lensed through awards chronologies and author surveys, before such things were easily accessible electronically. These compendia were the forerunners of every clickbait listicle you can find online today, minus the bait, no clicking required. Though these books have been in my possession for over a quarter century now, recondite little nuggets continue to emerge on the pan (did you know, for instance, that Irwin Ross published a short story in 1971 called “To Kill a Venusian” that was “an almost word-for-word copy of a quite famous story by Anthony Boucher, ‘Nine-Fingered Jack’”?). A few nights ago I went prospecting and was struck by a realization I couldn’t believe I hadn’t noticed earlier.

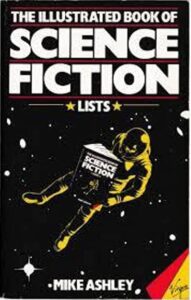

The artwork of both books is distinctly self-referential. The Complete Book of Science Fiction and Fantasy Lists shows planets and spaceships and floating prominently among them, a red volume; it’s this volume within the cover artwork that is titled The Complete Book of Science Fiction and Fantasy Lists, so here we have self-reference of the order of one. The Illustrated Book of Science Fiction Lists, meanwhile, more ambitiously depicts an astronaut floating in the blackness of space, with an open copy of The Illustrated Book of Science Fiction Lists, featuring a smaller version of himself on its cover, and so on, in a theoretically infinite regress. The straightforward interpretation of these artwork choices is that these books are nonfiction about genre, and so they frame it up visually. But these covers can also be seen as saying, “We know what we are, and when you read us, you will be entering a space in which there is room for you, the reader and explorer.”

It’s an invitation.

One way readers can feel invited into fiction is through narrative representation: the existence within stories of characters that represent or mirror their audience in terms of a specific community, ethnicity, or group orientation, such as, for example, BIPOC and LGBTQI+. At a more basic level, there’s one thing we all have in common when we read; for the duration of the text or audio narration, we are, axiomatically, recipients of story. The meta-aspect of the covers I mentioned started me thinking that perhaps one way that science fiction sets itself apart from other genres is by integrating a kind of secondary, underlying representation within its protocols, a representation of our interactions with story. I think this shows up in at least three distinct ways.

One, well-documented by now, is the depiction of characters in science fiction stories who are writers or—probably more sympathetically—fans and readers, or in some other fashion engaged with stories within their fictive universes. Anthony R. Lewis has compiled close to one thousand examples of this kind of recursion. I’d like to highlight a few, focusing on reader/fan characters that I believe are absent from his wonderful resource. In Stanislaw Lem’s His Master’s Voice (1968) the scientist Saul Rappaport reads science fiction novels—“attractive, glossy paperbacks with mythical covers”—as a way to try and generate ideas to decode a stellar message. In the episode “Welcome to My Nightmare” of the television series Amazing Stories (1985-1987), the protagonist Harry is so obsessed with film that his concerned parent admonishes, “Your mind is so hopelessly warped with fiction … that life is just a station break to you now! Sixty seconds to go grab a sandwich, and back into oblivion.” In Harry Turtledove’s eight book Worldwar (1994-2004) series, the recurring character Sam Yeager is well-versed in science fiction and draws upon it in his dealings with the aliens known as the Race. Colonel Jack O’Neill on the long-running show Stargate SG-1 (1997-2007) is clearly an sf aficionado, at one point identifying himself as James T. Kirk, and he’s not the only one in the expanded franchise versed in pop culture. Galaxy Quest (1999) is an obvious, easy-to-love entry. In a way, its much darker contemporary companion The Matrix (1999), though, also qualifies: everyone has been forced to consume story, and that story happens to be what we think of as reality. Wade Watts in Ernest Cline’s Ready Player One (2011) and Morgana in Jo Walton’s Among Others (2011) are more recent examples in popular and critically-acclaimed texts. Even Star Trek: Picard (2020-) couldn’t resist a nod in this direction. In the episode “Maps and Legends” the titular retired Admiral—well-established as a passionate reader throughout The Next Generation and now a historian—is shown owning a copy of Isaac Asimov’s The Complete Robot.

A second, more subtle way, of capturing our interactions with story in story is by including enactments of representation. Beyond whatever dramatic purposes they serve in a tale, these secondarily echo our finding vicarious representation through characters. A simple example that comes to mind, from various Star Trek movies and episodes, is the introduction of representatives of various worlds that occupy seats on the Federation Council. A more memorable instance, for those of you old enough to remember (or hey, HBO Max), occurs in the first-season Babylon 5 (1993-1998) episode “The Parliament of Dreams.” Commander Sinclair is tasked with representing Earth’s dominant belief system and struggles to arrive at a satisfactory choice. The episode famously ends with him introducing countless individuals in an incredibly long line, each one a member of a different belief system. The diversity of our search for meaning is powerfully brought home by means of representation, but the act of representation itself is also being made explicit by appearing within the narrative, which I believe accounts for part of the scene’s enduring resonance.

Finally, for the third manifestation of the meta-inclusivity that I’ve been discussing, I’d like to quote Samuel R. Delany. In his foreword to A Reader’s Guide to Science Fiction, by Baird Searles, Martin Last, Beth Meacham, and Michael Franklin, Delany writes:

There is a tradition of reader response to science fiction—printed and considered response—that is comparatively old. […] It is based on science fiction readers wanting to communicate with other readers about what they are reading now; and it manifests itself in hundreds of fanzines (amateur magazines about science fiction), hundreds of science fiction conventions each year, probably thousands of local science fiction clubs—and more hundreds of fanzines! It’s a tradition that, if academics do not at least take intelligent cognizance of, they will simply not be talking about the totality of the science fiction experience.

These words were published in 1979; update fanzines with blogs, Twitter, and so on, and Delany’s description still holds true today, perhaps even more so. This type of reader response, and the phenomenon of fandom at large, remain an incredibly fertile, energized arena of discourse, and directly influence the evolution of our genre. Regardless of our chosen medium, whenever we share our experience of a given book with someone else, we are involved, whether deliberately or unwittingly, in the construction of a narrative in which we and the story co-exist. The Internet has vastly facilitated our penchant for inventorying, taxonomizing and deconstructing stories and tropes. Case in point, consider “Indexed and Nerdy,” or “Bookworm” characters.

When we create lists, confer awards, and suggest canons, we are performing acts of storytelling. Though those narratives may not cohere until sufficient time passes, we’re nevertheless actively embedding ourselves-as-readers into the protocols of our genre and affecting the kinds of stories we’re more likely to tell, and how, contextually and culturally, we’ll interpret them.

The hallowed and highly useful SF Encyclopedia has entries for Recursive SF and Metafiction (the latter redirects to Fabulation), as well as Fandom, but not one for Representation.

If it’s true that in our genre we’ve engineered the deep, structural type of representation I’ve been writing about, it’s worth asking, why? Furthermore, while other genres, like mystery for example, certainly have their fare share of bibliophilic stories, they don’t embody the trifecta of meta-representation we’ve looked at, so another question is, why not? What, in this context, is special about science fiction?

I offer a tentative answer. Science fiction texts tend to make a uniquely double imaginative demand on us: first, that we, as per usual, enter the world of fiction, and secondly, that within this world we acclimatize ourselves to a cosmos that doesn’t mimetically map to ours. Fictional acts of representation on the one hand, and para-literary traditions of discourse and engagement on the other, help anchor us, providing an extra tether as we perform both bounds. By creating stories that feature characters engaging with fiction, but also in a more abstract way, by encoding the uniquely science fictional phenomenon of prolific reader response that Samuel Delany was writing about forty years ago, we provide ourselves with a more robust runway on the path to take off.

Then too, meta-representation may simply be a subcategory of science fiction’s salient ability to shine light back on ourselves. “It is the unique propensities of science fiction for self-reflexivity, in addition to its ability to reorient, that inspire me to return to it again and again,” writes Allison de Fren, Ph.D., and 2010 winner of the Science Fiction Research Association’s Pioneer Award. This may also show up in the specific ways that language itself is used in science fiction, as noted scholar Eric S. Rabkin discussed in his paper “Metalinguistics and Science Fiction” (1979).

The comedian Steven Wright once brilliantly quipped that he was a “peripheral visionary”: “I could see the future, but only way off to the side.” That can double as a pragmatic description of science fiction readers and dreamers at large. But besides peripheral visionaries, we’re also the beneficiaries of another special kind of gaze, one that by its very ability to reflect back allows us to venture out arbitrarily far into the night without the fear of getting lost.