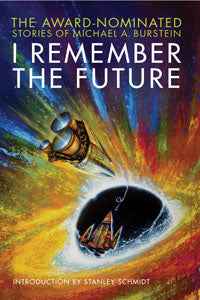

Paying It Forward

A Hugo Award-Nominated Short Story by Michael A. Burstein

I'm dying.

No one knows it yet. Having never married, I have no family to mourn my passing. I do have my fans, who would probably turn out in droves to say farewell if I had chosen to let them know in advance. But in the twilight of my time, I want to face this final passage alone.

Of course, I’m not completely alone. I still have my mentor, Carl Lambclear. I’ll email him tonight, and he’ll email me back, and just remembering how much he helped me will keep me going until the very end. We’ll exchange our latest story ideas, and share more turns of phrase that we both find appealing. Carl Lambclear is the one person I could open up to about my condition, and I’m glad that I did.

It’s the ultimate irony, I suppose, that once more I find myself having something in common with Lambclear. He, too, is familiar with the emotional gamut that accompanies an inoperable brain tumor; after all, many years ago, he died of the same thing.

* * *

It started long ago, at the beginning of the century. I think it’s almost impossible for anyone who didn’t live through it to fully appreciate the swinging moods that the world experienced. For the months before and after New Year’s Eve 2000, everyone all over the world seemed to harbor a quiet expectation that things would become new and different. The twenty-first century, a century of imagination and great wonders, was arriving, and optimism was the order of the day.

Of course, most of us sobered up after the economy tanked and September 11 happened and the other events of the ohs came to pass. With each tragedy, small or large, it was as if a curtain had plummeted down over another hope that was now irrevocably gone.

For me, the curtain came down when Carl Lambclear died.

I was in my early twenties, a recent college graduate dealing with one of the worst economic downturns to follow a time of great economic growth. Despite a double honors degree in Chemistry and Physics, I couldn’t find a job, and I didn’t really know what I would do with one if I had one.

Because what I really wanted to do was write science fiction.

My parents had waited until their later years to have their only child; and, as an unfortunate consequence, they both died of old age while I was still in college. But fortunately, they had also left me enough of an estate to take care of myself during that difficult time. And that meant I had a chance to explore what I wanted to do with my life, rather than having to take the first job that came in my direction just to support myself.

I had grown up reading the great works of science fiction, pressed upon me by my father. Although in his later years his tastes had turned to mystery novels, he still understood the ability of science fiction to unleash the imagination of a teenage outcast. And I had been so captivated by the works of Asimov, Clarke, Heinlein, and all the rest, that I simply could not imagine doing anything else with my life but trying to bring that sense of the fantastic to others.

And so I had been trying to establish myself as a writer of science fiction. I’d published a few stories in small markets while in college, but to no great acclaim. While pursuing my formal degrees, I had studied writing informally by reading book after book on technique, plot, character, setting, and whatever else seemed useful. But one book I had devoured above all others: Writing Short Science Fiction by Carl Lambclear.

It wasn’t just that I enjoyed Lambclear’s novels. I also enjoyed his ability to teach, to explain how he created the worlds that he did in a way to make them fascinating. Lambclear had a lot of advice on how to draw the reader in, and the advice was just as fun to read as his fiction.

On the day he died, I visited his webpage, and read about all the new books he was planning. It’s a strange phenomenon, I suppose, the dead leaving traces of themselves scattered around cyberspace as if they were still alive. Of course, I imagine people might have felt that way from the time the first person died who had a portrait painted. I remember reading mainstream mystery stories involving messages from beyond the grave, but not ghost stories and the like. There was nothing new about the idea of someone leaving a suicide note, or a clue to their murderer, but as technology progressed, the fictional and nonfictional deceased would leave answering machine messages, videotaped wills, and even emails set to go if a code word wasn’t entered into a computer on a daily basis.

But for me, the spookiest of such messages from the dead were the web pages.

A personal webpage—even a professional webpage, come to think of it—was a vivid statement in the ether, saying to one and all that this person exists. To visit a webpage knowing that the subject of it is dead is like talking to a ghost, and hearing about all the tasks that the dead one left undone.

So, when I heard that Lambclear had died, it spurred me to visit his webpage. I had never done so before; odd, I suppose, given how much I liked his stuff, but it had honestly never occurred to me to do so.

So I pointed my browser (Microsoft’s Internet Explorer on an iMac, connected via a 56K internal modem, if anyone still remembers those things) at his webpage and waited for it to download. The long amount of time it took surprised me. Most writers maintained web pages that were light on the graphics and easy on the text, which made downloading them rather fast, even over a simple phone line. But Lambclear’s page displayed elaborate graphics, and so I sat at my desk, staring at my computer screen and sighing as I waited for the bytelock to clear.

Finally, just when I thought my computer had frozen up completely, the browser bar filled all the way from the left to the right, indicating that the download was done. The picture on my screen made it evident why it had taken so long. Lambclear’s webpage displayed a simulation of the control panel of a spaceship, with digital displays and blinking lights. As I stared at it, dumbfounded, my speakers started playing beeps and whooshes to go along with the effect. Windows on the control panel flashed funny messages, warning of strange anomalies, asteroids, black holes, and wormholes, and requesting that I make course corrections so I wouldn’t hit anything.

I smiled. Although I doubted that Lambclear had designed the graphics himself, they did fit his style quite well. Lambclear wrote a lot of hard science fiction set on spaceships, rollicking adventure stories set against a rock-solid background of real physics.

Something else fit his style as well. The graphics were intense on the eyes, but they didn’t make the webpage confusing to navigate. When I moused over all the graphics, nothing happened. Lambclear had placed a list of links to the other pages on the site over on the left of his main page, away from the graphic of the spaceship control panel. And each link was a simple word, such as “Home,” “News,” “Biography,” “Novels,” and “Bibliography.” The link right under “Home” was to a site map, so I knew that despite the fancy setup, he wanted his information to be as accessible as possible to any visitors.

And on the bottom of the page sat a link that read, very simply, “Send me email.”

I stared at it for a long time with regret. I had never emailed Lambclear, and clearly he had been interested in receiving feedback from his fans. If only I had thought of it before, I could have emailed him, let him know how much his work meant to me, and how much I wanted to emulate him.

But it was too late. Lambclear didn’t even have a family to whom I could send my sympathies; he had remained a solitary bachelor until his last day. There was no one to whom I could properly express my appreciation for his work and my sorrow for his passing.

No one except…

I moused over the “Send me email” link and watched it blink back and forth between white and red. Finally, I clicked on it, bringing up my email program with the “To:” field already addressed to Lambclear’s America Online account (again, does anyone still remember them?). For a brief moment, I felt silly—but only for a moment. I stared at the screen, looked out my window at the autumn leaves just beginning to turn on the trees, and then I composed this message:

Subject: Hello

Dear Mr. Lambclear,

I’m sorry I never got in touch with you before. I’m a big fan of your works, from the Ethereal Web stories to the Five Universes novels. I even have a copy of your first short story collection, The Universe Off to the Side, which my father gave to me as a birthday present when it first came out.

I doubt you’ve ever heard of me, though, and I hope you won’t think it forward of me to write. (Your webpage did seem to invite email.) I’ve been trying to write science fiction myself, with no real success. I have to admit that I’ve been emulating you, with the hope that one day you might read my stuff and realize that we were kindred spirits—at least, as far as our tastes in writing.

I’m sorry that will never happen now. I do wish I had written to you sooner. Although I knew you were something of a recluse, the afterword in Writing Short Science Fiction seemed to indicate that you were willing to hear from your fans. But I just never had the inclination to write to you. In the back of my mind, I think I was waiting until I had published enough stories myself so I could approach you as a fellow colleague. But I guess, as I said, that can never happen now.

I hope you can forgive me for waiting. Thank you for all your stories. You will be missed.

I clicked the SEND button on my computer screen, and the email went off to its destination. I felt better. Even though I knew that Lambclear could never know of my appreciation of him and his work, at least I knew about it, and that made a difference.

I went to bed that night feeling a little less sad about his passing.

A reader of this file, if anyone finds it, could probably guess what happened next. But as I write this, I still choose to approach the event slowly, like I did that long-ago morning.

My alarm clock went off at 7 AM, blaring its grating tone as usual. I could have slept later, I know, but my parents had instilled in me a fear of sleeping away the days of my life. I pulled myself out of bed, walked to the kitchen, and brewed a cup of fresh-ground Colombian coffee to help me wake up. Still in my blue chamois pajamas, I sipped from my father’s old porcelain mug, sat down at my computer, and downloaded my email.

And among the voluminous spam and occasional email from friends, I found a reply from the account of Carl Lambclear.

At first I was confused, and I almost choked on my hot beverage. Lambclear was dead; how could he have replied to my note? Perhaps a friend was cleaning out his mailbox. Or maybe Lambclear had set his computer to send out automatic replies, acknowledging receipt of email. Whatever the reason, I knew an obvious way to find out. Just open the email and read it.

I hesitated, as unwilling to resolve my situation as the familiar quantum cat. So long as I left the email closed, I could imagine that Lambclear lived; but the moment I opened it, I would come face to face again with the bald fact of his death.

I shook my head, sighed at my own silliness, opened the email, and read it. And when I came to the end of the email, I leaned forward and read it again and again.

Subject: Re: Hello

Dear fellow traveler,

It was an absolute delight to receive your missive from yesterday. As a matter of fact, I have heard of you. I keep up with all the magazines, even the semipro ones, and I fondly recall one of your stories. If my memory does not fail me, yours is the story about the young girl who runs off to join an interstellar circus. Good stuff, even if the writing is a bit awkward in places, and the plot a little thin. But writing weakly is a phase we all must pass through, and within your story I do espy the seeds of better work.

However, the point of my reply is not to criticize your work, as I would hesitate to do so without a formal invitation. Rather, I am writing to tell you of my gratitude in knowing how much my work has meant to you. It may surprise you to hear this, but in point of fact I do not hear from many of my fans, even those who would aspire to join me in my calling. I presume most people are put off by my reputation of reclusiveness, and are therefore hesitant to intrude upon my privacy, no matter how delicately they might.

But I must admit, now being in the autumn of my life, I find myself more willing to be an active participant in the world than I have been before. And since your letter arrived at this propitious moment, I feel that perhaps I owe you a little bit of the assistance that was offered to me at the beginning of my career. I would like to offer you the same help, giving you advice on your own stories in the hopes that you will grow to be the best writer that you possibly can.

In other words, if you are willing, I would be more than happy to begin a correspondence.

Sincerely yours,

Carl Lambclear

After reading the message three times, I leaned back slightly in my chair, sipped my coffee some more, and pondered. The email was impossible. Lambclear was dead; notices of his death had appeared on all the usual places, including the Locus and SFWA web pages. Lambclear could not have replied to me; therefore, by simple logic, someone else must have done so, pretending to be Lambclear.

But who would have done that? For a moment, I had the fleeting thought that perhaps Lambclear actually did have a family. Was there a secret wife who replied to my message? Or maybe a secret child? But I dismissed that notion as quickly as I came up with it. It simply didn’t make any sense, given the tenor of the reply.

Still, someone must have been reading his email, and whoever it was seemed intent on playing a joke on me. Rather than fall into the trap, and be made a laughingstock, I carefully composed my next email to dissuade the prankster. It went like this:

Subject: Re: Hello

Dear “Mr. Lambclear”:

Whoever you are, this joke is in poor taste. Both you and I know that there is no way in the world Carl Lambclear could have responded to me. All I meant to do was express my appreciation of his work, and you poked fun at me for doing so.

Leave me alone.

I sent it out within the hour, and then spent the rest of my day writing. I managed to get my thousand words done, not bad for the day’s work. And, as was my habit, I refused to check my email while working. I knew too many aspiring writers who had fallen into that trap and never written a word.

Furthermore, that night I had no time to read my email after I finished my thousand words, as I went out on an unsuccessful blind date. The date was disastrous enough that I still recall it today; still, the less said about it, the better. So the next morning, when I once again was drinking coffee in front of my computer, I found another ostensible reply from the account of Carl Lambclear.

I sighed, thinking that this was absolutely ridiculous. I had already told off the anonymous person who had emailed me the first time; I didn’t really want to have to go through this again. I highlighted the email and prepared to delete it. And then a random piece of advice flitted into my head and stayed my hand. Some writer once said that any experience, no matter how bad, was fodder for the typewriter. Perhaps this message might lead to a story idea. At any rate, it couldn’t really harm me just to read it.

So I clicked on the email, opening it. And read the following:

Subject: Re: Hello

Dear fellow traveler,

I must admit being somewhat perplexed as to both the tone and the content of your last message. Here I am offering you a chance for personal feedback from me, and you react with hostility. From what you said in your first note, I was under the impression that you found my work enjoyable. Was I mistaken? Should I have not written back with the gratitude that I did?

Please rest assured that it was indeed I who responded to you, that no one was poking fun at you, and that I am in fact Carl Lambclear.

However, if I do not hear from you again, I will assume that you wish me to leave you alone, as you so explicitly indicated in your last sentence.

Sincerely yours,

Carl Lambclear

It was only after I read the email that I noticed the attachment accompanying the message. Normally, I would approach an attachment from a strange email address with wariness, but curiosity took over. Besides, people never usually wrote computer viruses for Macintosh computers, so I figured the file would yield no problem.

I opened the file and began reading it. After a moment, I choked. Lambclear, if it really was he, had written a critique of “Alien Circus,” my story about the young girl who runs off to join an interstellar circus.

At first, I felt insulted. How dare this person, pretending to be Lambclear, take it upon himself to criticize my work without invitation?

Then I began to read the critique.

The writer, whoever he was, had made some very cogent points about the flaws in my story. As I continued reading, I felt my anger melt away. The writer’s gentle phrasing and spot-on analysis rendered me more grateful than upset. Lambclear clearly knew what he was talking about—he showed great insight in his comments—

I shook my head. When had I decided to think of this person as Lambclear?

I reached the middle of the document and stopped reading in order to ponder its existence. If I had written to Lambclear but a year or two ago, and gotten this email in reply, I wouldn’t have questioned its veracity in the slightest.

And yet, how could Lambclear have sent me this email today, given the incontrovertible fact that he had died? Could he possibly still be alive? He wouldn’t perpetrate a death hoax, would he?

A thought occurred to me, prompting me to open the first message I had sent Lambclear. I noticed something interesting; I had never mentioned in my note that Lambclear was dead. It didn’t seem important at the time, but now I wondered. Could whoever it was had taken my email as an invitation to give me the mentoring I so desperately wanted?

And the funny thing, the two emails did sound like him. I went back to his book on writing and some of his essays, and the style felt very similar. I considered hiring someone to do a textual analysis of the two emails and the critique to prove that Lambclear was really composing them, but it didn’t seem worth it. Kind of like killing a fly with an atomic bomb.

Still pondering and puzzled, I returned to the critique to see what else he had said about my story. My thoughts flipped back and forth over the question of whether or not Lambclear himself could have written this document.

And then, when I finished his critique of my story, I saw something that clinched my belief that my correspondent might in fact be Lambclear. I pulled Writing Short Science Fiction off my shelf again, and riffled through the pages, until I came to the page I remembered.

In this book on writing, Lambclear had given the subconscious mind a name. He called it “George,” and frequently noted that George would tell him to do this, or George would tell him to do that. Well, in the critique of my story, he ended with this piece of advice? “I suggest you get in touch with your inner George.” Now, the possibility existed that some other close fan of Lambclear’s work had written that final sentence. But it seemed unlikely, especially when taken together with all the other evidence I had that Lambclear himself had written back to me.

And yet…rationality said otherwise. How could I reconcile the fact that Lambclear was dead with the fact that he was writing to me? I had grown up a rationalist, an agnostic, a skeptic in the face of superstition. How could I believe that I was now corresponding with the dead?

I wrestled with what to do for few hours, finding myself too distracted to write fiction. Finally, I wrote another email:

Subject: Truth

Dear Mr. Lambclear (?),

Thank you very much for your critique of “Alien Circus,” and for your willingness to reply. I only wish I had had the opportunity to run the story by you before it saw publication! Still, some of your comments suggest to me the possibility of a sequel, which I feel would have a higher quality than the original story. And so it goes, I guess.

You must have noticed that although I removed the quotation marks from around your name, I’ve added a question mark in parentheses afterward. Please do not take that as an insult, only as a representation of my confused state. You see, after reading your critique, I am convinced of a few things. I am convinced that you understand the art of writing very well, and that you also have great skill as a teacher. I am also convinced that you have a deep understanding of the field of science fiction, and what makes a story evoke that sense of wonder we all strive for.

And yet, for reasons I do not want to mention explicitly, I find it extremely difficult to believe that you really are Carl Lambclear. Not to be insulting, but there are compelling reasons for me to believe otherwise. I hope you will understand what I mean, and still be willing to continue this correspondence that I may have inadvertently started. But I further hope that perhaps you can tell me something to clear up my confusion.

The email sent into the ether, I returned to my daily quota of words. I recall how sometimes the critiques I received in writing workshops would make me freeze up for days on end, unable to write anything. It pleased me to discover that Lambclear’s critique had the opposite effect. I zipped through my thousand-word quota, and even doubled it before I declared my working day over.

And the next morning, when I checked my email, I found another message from “Carl Lambclear.”

I noticed he had changed the subject line.

Subject: What is truth?

Dear fellow traveler,

I am delighted to see that you have come around somewhat, and are willing to accept the fact that I am who I say I am. (I remind you once again that you were the one who initiated our correspondence, not I.)

I must admit, I haven’t received too many emails recently; or at least, not emails of any major interest. I suspect that most people doubt I would bother replying, for those same “compelling reasons” to which you obliquely referred. But you, my young friend, chose to write to me anyway, and for that, I hope to repay you.

Essentially, I plan to share with you seeds of story ideas that might blossom under your tutelage. My wish is that you grow enough in your talent to be able to take these story ideas and make them uniquely yours. But let me begin with an idea that is uniquely mine, and which is also one that might make you feel better about corresponding with me.

Let us posit the following scenario.

Suppose a writer knew he was dying. An older writer, but not one who has yet reached what most would consider the twilight of one’s life, but rather just the autumn. Such a writer might feel many things: desperation, anger, and fear are the obvious ones, although one cannot omit the possibility of feeling peace or a sense of completion. A psychologist could discount that, however, and suggest that the writer might even go through the five stages of dying: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and finally acceptance.

But the writer might do something else instead. Suppose that writer was also a Ph.D. physicist and an expert computer programmer, and he wanted to make sure that he would be remembered. What might he do? How does a person with a technical background and a ceaseless imagination deal with the inevitable conclusion of his existence?

I know that such a scenario must be light-years away from your own mind, but that makes this all the more interesting a challenge. If you can figure out my idea, you might have the makings of an excellent spinner of tales of science fiction.

Sincerely yours,

Carl Lambclear

I didn’t know it then, but this was only the beginning of the meat of my emails with Lambclear. Lambclear called it “Campbelling” a story, named after the most influential editor in the field of science fiction. John Campbell would give story ideas to his writers, and ask them to write the stories. They would take his ideas and run with them; for example, Isaac Asimov’s “Nightfall,” which was once voted the best science fiction story ever written, was based on an idea given to him by John Campbell. Lambclear loved to throw ideas in my direction, and over the years, many of my most well-regarded stories had their roots in Lambclear’s suggestions. I suppose I could come clean now, and point out which stories of mine came from Lambclear’s suggestions and which didn’t, but I think it is best if I do not. I have to leave something for the scholars to argue about, after all. (Ah, a writer’s ego rears its ugly head once again; why should I assume that future scholars will have any level of interest in my scribblings?)

But I’m getting ahead of myself, because on that long-ago night when Lambclear first sent me a story idea, I had no idea where this would all lead. Picture me as a young, confused writer, who still had no idea what Lambclear was getting at. I suppose I could have terminated our correspondence right there and then, or just emailed him back innocuously. But the idea had created some deep feelings within me, and I decided to make my distress evident.

Subject: Re: What is truth?

Dear Mr. Lambclear,

I’m afraid I’m totally at a loss as to how to develop that idea you’re suggesting. In fact, I’m not quite sure why you’re even suggesting it to me in the first place. After all, if it’s just a story idea, why not write the story yourself? And if it’s more than a story idea, why hint at it in such an odd way?

I actually have more experience with death than you may expect or realize. You see, although I’m just out of college, both of my parents have passed on. I was there for each of them, and I helped my mother and my father go through their struggles before dying.

Furthermore, Dad was a scientist, much like yourself, and Mom a computer programmer. So to suggest, as you did, a story idea in which someone with technical expertise finds himself dying—well, it hit me a little too close to home. Literally.

My guess, though, is that you didn’t know. Otherwise you wouldn’t even have suggested that idea. But maybe this is why I’m having trouble spinning fiction out of your idea.

Or maybe I’m once again having trouble dealing with the question of who you really are.

Please stop playing games with me. Just be up front and let me know what’s going on.

Subject: Re: What is truth?

Dear fellow traveler,

My first reaction to your latest note was to sigh, as I felt heavy with guilt of unintended actions. I truly did not mean to bring up any unpleasant memories. As you ascertained, I knew nothing of your family background, and had no idea that your parents were deceased. Please allow me to offer my sympathies, belated though they may be.

That said, I do feel obliged to point out to you what you must have already learned if you have truly read my book on writing. The best stories come from deep within a writer’s soul. The death of your parents may hurt you deeply, so deeply that you choose to withhold your emotions; but if, instead, you were to tap that resource, you would probably find a rich vein of story ideas that would never be depleted.

In any event, I reread “Alien Circus” and it reminded me again that you do have a talent I could nurture, even if it is still in its most rudimentary form. (Please do not take that as an insult; even well-established writers need constant nurturing, and the more mature and comfortable writers are with their level of talent, the more they understand and accept this.)

So let me help you with the development of the story idea I suggested. Again, the question I posed is: suppose a writer with a strong background in Physics and Computer Science discovered he was dying? What might he do?

To my way of thinking, the obvious answer is that he might try to find a way to stave off the grim reaper. Our field has plenty of examples of stories of immortals, or near-immortals; and yet surely, our field could support many more. So I played on this idea for a while, and came up with my own conclusions.

The first thing that such a person might do is attempt to download his personality into a computer, so that he could continue living. Of course, as a few philosophers have been quick to point out, that doesn’t necessarily mean that the writer himself would continue to feel alive. Instead, others who interact with the computer program would swear that the person was alive and intelligent, so his influence would live on in an explicit way even if he himself did not.

But, sadly, current technology doesn’t yet allow for an actual uploading of a mind; our brains are still far too complicated for us to understand that completely. However, if our imaginary writer had the skill, he might write a computer program that could simulate himself as a rudimentary form of artificial intelligence. Perhaps even as an AI which could pass the infamous Turing test.

(As a side note, it seems to me that the writer, relying only upon his own judgment, would program the computer with only his best qualities, and leave out the worst. After all, we all imagine ourselves to be nobler than we really are.)

Doesn’t that strike you as a fascinating idea to play with?

Ah, but I hear you ask? what else? What other ideas come to mind?

Well, try this one. Suppose this writer, having a background in Physics, figured out a way to connect his computer to another universe via a wormhole. Perhaps travel between universes is not possible, but communication is. If so, it might take the imagination of a science fiction writer to make it work. Could that writer arrange for all his incoming email to fall through that wormhole and end up in the mailbox of another version of himself? And might that version then pick up his communications where the original one was forced to leave off?

Think on it, my young friend.

Sincerely yours,

Carl Lambclear

Subject: Re: What is truth?

Dear whoever,

Are you saying you’re a Carl Lambclear from another universe? Are you saying that you’re a computer simulation of the Carl Lambclear who just died? WHO ARE YOU?

Subject: I am that I am

Dear fellow traveler,

I believe the standard reply on the Internet is ROTFL, for the phrase “Rolling On The Floor, Laughing.” Nowhere in my email do I mean to imply that what I wrote is the truth! My idle thoughts were merely an exercise in speculation, nothing more. I’m not saying anything about the real world. I’m just doing what we science fiction writers always do, positing scenarios and generating story ideas.

Of course, you may choose to believe what you wish, but remember the curse that falls upon the heretic. I dare say that if you took these bizarre insinuations to anyone but myself, they would look at you askance and inquire as to what weed you were smoking. Those who would hang on your every word are probably also those with whom you would be most reluctant to share these ideas.

I will finish this email with the following offer, reiterated. I find myself with much time now, and can think of no better way to use my time than to help you along. If you would have me as your mentor, I would have you as my pupil. I only ask that you no longer question me on how and why, but accept this for being just what it is.

Sincerely yours,

Carl Lambclear

I took Carl up on his offer, and with his help, my writing blossomed. I managed to crack a few minor markets at first, semiprozines and webzines, until finally I figured out how to make a story work for a larger audience. And then, by the purest luck, I managed to catch the wave of the science fiction renaissance, the so-called Second Golden Age.

My stories were some of the first to appear in Analog, Asimov’s, F&SF, Absolute Magnitude, and Artemis when the kids who had grown up on the fantasies of J.K. Rowling and Tamora Pierce suddenly turned to science fiction to satiate their appetites for that undefinable sense of wonder. Of course, these things do come and go in waves. Eventually, the wonders seemed pedestrian again, and the circulation and sales dropped as they had many times before. But they will grow again at some point in the future; of this I am sure. As it says in Ecclesiastes 1:9, “That which has been is that which shall be; and that which has been done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun.”

After having cut my teeth on short stories, I finally began publishing novels. My novels sold well enough for me to make a living, and garnered me some minor critical acclaim, even an award or two. And so the years passed. I need not recount them here in any sort of excruciating detail; anyone interested can refer to The Scenes of Life, the autobiography I uplinked just ten years ago in 2060. My estate will surely find the royalties useful for settling old debts. Instead, I turn now to the end of the tale, the last few emails I shared with my mentor.

The emails in which I finally unearthed the strength within my soul to tell Carl Lambclear the truth.

Subject: Cancer

Dear Mr. Lambclear,

I’m dying.

I didn’t want to tell you this news. I know how much we’ve avoided talking about death, ever since the beginning of our emailing back and forth. I suspect I know why, and I’m sure you do too.

It’s particularly disheartening, because the reason I’m dying is that I have an inoperable brain tumor. There is an irony in all this, I suppose, but again, I wouldn’t feel right pointing it out to you. Not after all these years of your help and guidance.

I know I have very little time left; unfortunately, I have no way of knowing exactly how much. I must admit that part of me feels the need to ask you how you managed, after—well, you know what I mean. But the other part would hesitate to dispel the magic, and so I refuse to ask for a peek at the man behind the curtain.

The email sent I went back to my bedroom to try to get some sleep. The pain came and went, but by popping THC and plugging my head shunt into the wall, I managed to doze off and even have a few pleasant dreams of old friends.

* * *

My EC chirped, waking me up, and called out the time in a flat monotone. “Eleven twenty-two PM,” it said. The middle of the night. I gently creaked out of my bed, pulled my tattered blue robe around me for warmth, and glided into my living room. The wall screens remained dim, due to the lateness of the hour.

“Messages,” I called out. Perhaps it was old-fashioned of me, but I never wanted the whole house connected, just this one room, which was why I had to leave my bed for the alert.

“You have twenty-seven messages,” the room said.

“Delete all spam.”

“You have one message,” the room said. As I had expected.

“Display,” I said.

And the screen on the walls turned bright with Carl Lambclear’s final message.

Subject: Re: Cancer

Dear fellow traveler,

So it has come down to this. In the end, we really are fellow travelers.

I am truly sorry to hear your news. I still remember my first reaction when I found out about my own terminal condition. You may recall how I refused to let anyone know about my cancer until I had finally passed on. My agent was good at keeping secrets, and she handled the announcement and the estate matters very well, or so I have always felt since.

Because we are fellow travelers, my young friend (and may I still call you young?), I understand your feelings. We strive for immortality, all of us, in our myriad ways. Some of us run for public office, in the hopes that we will change the course of the world. Some of us teach, in hopes that out of the thousands of students we encounter, one will blossom. Some of us get married and have children, so that a little bit of us will survive in a fellow human being’s DNA. And some of us create, whether it be art, music, poetry, or stories, in hopes of communicating to the future that once we were here, and that once we mattered.

In the end, however, from dust we sprang, and to dust we shall return. Even I was not immune to that, however much it may seem otherwise from our years-long correspondence. You know that I died, or at least a version of me did; and that is something you were never able to shake, no matter what.

But, as I said, I feel greatly for you. And so, at some expense to myself, I have decided the time is ripe to provide you with my solution. I have sent you an attachment to this email. I assure you that it is not a virus, nor anything of a malicious sort.

For reasons that will soon become clear to you, I am afraid that I will be unable to continue our correspondence for much longer. And so, having taken note of your salutation lo these many years, I would like to offer you one final hand of friendship. After all, we are no longer mentor and student, if we ever were. We have long passed into the roles of colleagues, equals in our field. And so, we should address each other as such.

Feel free to call me Carl.

Sincerely yours,

Carl

I read Lambclear’s—I mean Carl’s—note with tears welling up in my eyes, until I could no longer see. I removed my glasses and wiped them on my robe, and then the house brought me a tissue and I blew my nose.

Eventually, I managed to regain my composure, and I took a look at the attachment Carl had sent me.

I am not now, nor have I ever been, a computer programmer of any sort. Even today, when one programs the more complex computers by simply telling the less complex computers what you want them to accomplish, I still would have no idea what I’d be doing.

Nor am I a physicist, despite my degrees. My education is so far in the past, in any event, that I can barely understand the mathematics of the cutting-edge theories proposed today.

But I am a science fiction writer of many years, and I can comprehend certain concepts far better than the ordinary person. And as a science fiction writer, I am now prepared to accept even the most outlandish ideas that others might dismiss out of sheer mundanity.

Carl’s attachment was a computer program. He had sent me the same program he had created shortly before he died, the program that allowed him to communicate with me. I tried to decipher it at first, but the coding was far too obscure for me to grasp.

Fortunately, Carl’s program was filled with comment lines, laying out every step of what it did. The comments made it trivial to command my system to execute the program. And as an added bonus, I now know just with whom I was communicating all these many years, and I no longer have to guess if Carl’s emails came from an artificial intelligence, from another universe, or from something or somewhere else that no one could ever guess. Because in the comment lines, Carl explained how he had managed to apply the Tegmark Hypothesis.

Max Tegmark, a physicist who did much of his work at the turn of the millennium, when I was just out of college, had proposed an interesting take on the Many-Worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. Many-Worlds, proposed by Hugh Everett in 1957, explained away the paradoxes of quantum uncertainty by postulating that every time a decision has to be made, the universe splits into two, yielding an infinite multitude of realities, sometimes referred to as the multiverse. Well, Tegmark looked at this bizarre concept and proposed an even more bizarre idea of his own, which came to be known by his name.

The Tegmark Hypothesis can be summarized as follows: The only realities you continue to be aware of are those in which you survive.

In other words, suppose you do an experiment where you ask an assistant to push a button which will randomly cause a machine gun to either fire or not fire. You position yourself exactly in front of the gun, so that if the gun fires, you have no chance of surviving.

Here’s where quantum mechanics comes into play. It is certainly possible for your assistant and for the rest of us to observe the experiment and recoil in shock at the sudden explosion of a bullet into your chest. But because there are an infinite number of tracks upon which the universe can run, you yourself will never feel the bullet. For you to be a valid observer, your consciousness must follow a track along which it will never—can never—be snuffed out. Because the alternate way to phrase the Tegmark Hypothesis is this: You can never have any awareness of realities in which you are dead.

Carl’s program opens a connection to computers in other universes, and seeks out the universe in which “I” continue to live, forever and ever. The program will reach that version of me, and explain to that version exactly what is happening to me, in my universe—which is, of course, the only universe which matters to me. The program will bring a message about my life to my other self, and propose that my other self keep the memory of my existence alive in this particular world, doing exactly what Carl started doing those many years ago.

And so now I know what I must do. Web pages are years in the past, of course. We no longer surf websites on the World Wide Web; rather, we visit Holosites in the Universal Database. But email, in whatever form one calls it, is still the same.

Carl’s program was easy to download into my own machines. I do not have to wonder if it scans my files and reproduces an artificially intelligent copy of myself, for I now know that it does not. Nor do I have to concern myself with the entropic problems of creating a gateway into another universe, for that gateway is only for computers to navigate. And because I know what will happen, it no longer matters to me that Carl’s program cannot keep my “me-ness” intact. Within a week or a month, I know I shall be gone, and in the meantime, I must keep my shunt plugged into my system. Although it may be immodest of me, I imagine that on the day I die, some young fan who aspires to write will visit my site and will see the recently installed link that encourages fans to email. I imagine that the fan will hesitate, just as I did so many years ago, and then decide to send one more email into the ether, as a tribute to the author of that fan’s admiration.

And when that happens, my system will be ready. Carl’s program is set, and the young fan will receive “my” reply. With luck, my encouragement will spur my correspondent into a full-fledged calling as a writer. Another, immortal, version of myself will help that fan, in the same way Carl helped me and generations of writers beforehand helped him. All of our influence will be felt throughout the centuries. And none of us will be forgotten.

It pays to pay it forward.

Afterword

A few people who have read my stories have come to notice a theme I tend to revisit again and again—the question of how we will be remembered in the future. Nowhere is that more evident than in this story, which was inspired by the passing of writer Charles Sheffield.In 2002, Charles Sheffield died of a brain tumor. A decade before, I would have acknowledged his passing somewhat more remotely, as I wasn’t personally acquainted with him or any other science fiction writers. But Charles I knew, and not just as a remote writer I admired, or as a writer I met through a workshop. I had met Charles on the convention circuit, and he had befriended me like he befriended so many others.

His death hit me in a different way from Isaac Asimov’s, or even Damon Knight’s earlier that year. I suspect it was partly because Charles died exactly twelve years after my father had, to the day. I found myself thinking about Charles a lot, and while I was thinking about him I decided to visit his webpage, which I had never done when he was alive.

What I found I already described in the story as Carl Lambclear’s webpage. And like the unnamed protagonist, I moused over the email link, and contemplated what might happen if I sent Charles a final email. And at that moment, in a flash, the entirety of the story “Paying It Forward” came to me. I outlined it immediately and began to write.

Settling on the title of this story was difficult for me. The title “Paying It Forward” popped into my head from the very beginning, and I couldn’t get it out of my mind. But a movie called Pay It Forward, based on a book of the same name, had recently been in theaters, and I knew that titling my story “Paying It Forward” could lead to slight confusion. Still, I wanted to evoke Robert A. Heinlein’s statement about how in the field of science fiction, we don’t pay it back, we pay it forward, and there was no other title that seemed to fit.

Charles Sheffield died in November 2002. I finished the story in January 2003, and Stan bought it for Analog without requesting a single change (thanks once again to Nomi for fixing it before I sent it to him). The story came in second for the Hugo Award. I have to admit that I’ve always been surprised that the story didn’t make it from the preliminary to the final Nebula ballot, since many writers have told me how much this story has meant to them. But in the end, the awards and award nominations are just another way for folks to express their appreciation for one’s work, and with this collection I finally have a chance to reciprocate.